LAPAROSCOPIC

SURGERY FOR RENAL STONES: IS IT INDICATED IN THE MODERN ENDOUROLOGY ERA?

(

Download pdf )

ANDREI NADU, OSCAR SCHATLOFF, ROY MORAG, JACOB RAMON, HARRY WINKLER

Department of Urology, The Chaim Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer, Israel and The Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Israel

ABSTRACT

Purpose:

To report the outcomes of laparoscopic surgery combined with endourological

assistance for the treatment of renal stones in patients with associated

anomalies of the urinary tract. To discuss the role of laparoscopy in

kidney stone disease.

Materials and Methods: Thirteen patients

with renal stones and concomitant urinary anomalies underwent laparoscopic

stone surgery combined with ancillary endourological assistance as needed.

Their data were analyzed retrospectively including stone burden, associated

malformations, perioperative complications and outcomes.

Results: Encountered anomalies included

ureteropelvic junction obstruction, horseshoe kidney, ectopic pelvic kidney,

fussed-crossed ectopic kidney, and double collecting system. Treatment

included laparoscopic pyeloplasty, pyelolithotomy, and nephrolithotomy

combined with flexible nephroscopy and stone retrieval. Intraoperative

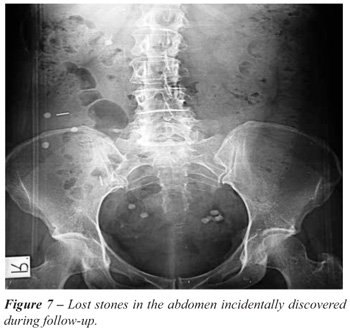

complications were lost stones in the abdomen diagnosed in two patients

during follow up. Mean number of stones removed was 12 (range 3 to 214).

Stone free status was 77% (10/13) and 100% after one ancillary treatment

in the remaining patients. One patient had a postoperative urinary leak

managed conservatively. Laparoscopic pyeloplasty was successful in all

patients according to clinical and dynamic renal scan parameters.

Conclusions: In carefully selected patients,

laparoscopic and endourological techniques can be successfully combined

in a one procedure solution that deals with complex stone disease and

repairs underlying urinary anomalies.

Key

words: kidney; laparoscopy; nephrolithiasis; genitourinary abnormalities

Int Braz J Urol. 2009; 35: 9-18

INTRODUCTION

Endourological

techniques have revolutionized the treatment of urinary stones to the

point they have rendered open stone surgery anachronistic (1). Procedures

like open ureterolithotomy, open nephrolithotomy, or open pyelolithotomy

have become anecdotal. However, patients with large stone burdens and

associated renal malformations are prone to require multiple endourological

procedures in order to have their stones retrieved and anomalies repaired.

Thus in these selected patients, open stone surgery can certainly be considered

reasonable (2). In centers with established experience in advanced reconstructive

laparoscopy, this can be a feasible option if the goals of stone clearance

and correction of malformations could be achieved in a single procedure.

Incorporating laparoscopic techniques confer these patients surgical efficacy

combined with the advantages of minimally invasive surgery.

In the present paper, we describe our experience

and evaluate the outcomes of laparoscopic surgery in combination with

endourological procedures involving a variety of cases of renal stones

in the setting of underlying urinary tract malformations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The

data of twenty-nine patients who underwent laparoscopic procedures for

kidney stones between January 2004 and May 2007 were retrospectively analyzed.

Retrieved data included indications for intervention, stone burden, associated

malformations, perioperative complications and outcomes in terms of functional

results and stone free status. Fifteen patients underwent laparoscopic

nephrectomy due to non functioning kidneys and were not included in the

present study. One patient underwent laparoscopic pyelolithotomy without

harboring underlying malformations and thus was also excluded. The remaining

thirteen patients underwent laparoscopic stone removal and reconstructive

procedures combined with ancillary endourological assistance as needed.

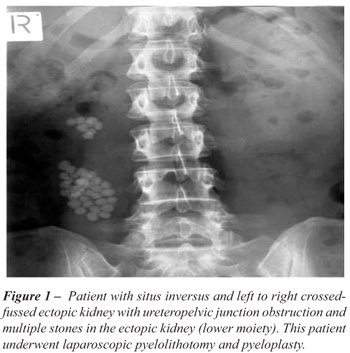

Preoperative stone scenario and associated anomalies are detailed in Table-1

and Figures-1 to 3. All cases were discussed with the endourology unit

and considered unlikely that stones and underlying anomalies could be

efficiently addressed with a single endourological procedure. Three patients

had previous unsuccessful endourological procedures, with inability to

gain percutaneous access and significant residual stones after nephroscopy

among main causes of failure.

Patients underwent preoperative anatomical

and functional evaluation with non contrast CT scan and either intravenous

pyelography or diuretic renal scans in cases of suspected ureteropelvic

junction (UPJ) obstruction. Postoperative assessment consisted of x-rays,

ultrasound, and/or CT as appropriate. A diuretic renal scan was performed

in patients who underwent concomitant pyeloplasty.

Surgical procedures and their technique

are summarized below. Combinations were used to deal with specific patient

necessities.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Laparoscopic

Pyeloplasty and Pyelolithotomy / Flexible Nephroscopy

The operative room setting includes one

laparoscopic cart and one endourological cart to enable simultaneous laparoscopy

and nephroscopy. Using a four port transperitoneal approach, the ureter

is identified and followed cranially, the UPJ is exposed and the renal

pelvis dissected. The renal pelvis is opened above the UPJ, the ureter

is spatulated on its lateral aspect and dismembered. Stones in the renal

pelvis are removed with an atraumatic grasper and placed in a laparoscopic

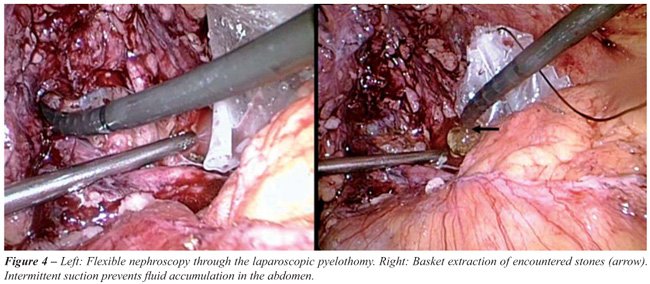

bag. A flexible cysto-nephroscope is passed through one of the 10 mm ports

and guided laparoscopically through the opening in the renal pelvis. The

kidney is systematically inspected and calyceal stones removed with a

basket or fragmented with Holmium:YAG laser lithotripsy. A double J stent

is introduced in an antegrade fashion, the renal pelvis is reduced as

needed, and ureteropelvic anastomosis is performed with two (one posterior

and one anterior) 4/0 polyglactin running sutures. A percutaneous drain

is placed and the bag with stones removed (Figure-4).

Laparoscopic

Nephrolithotomy

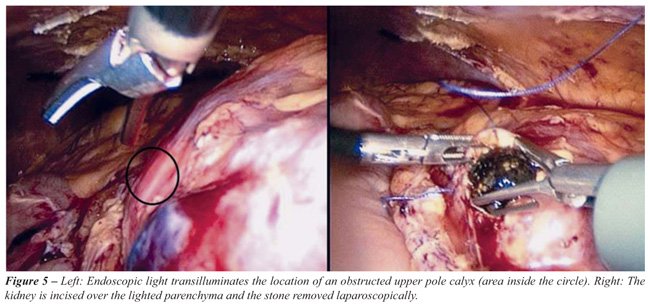

A “cut for the light” technique

was used when calyceal stones were associated with infundibular stricture,

obstructed hydrocalyx, or calyceal diverticulum. After widely incising

the renal pelvis, the flexible cysto-nephroscope is brought at the obstructed

calyx containing the stone and a small laparoscopic nephrotomy is made

in the kidney as indicated by the endoscopic light. The stone is removed

and the kidney sutured with one layer 2/0 polyglactin (Figure-5).

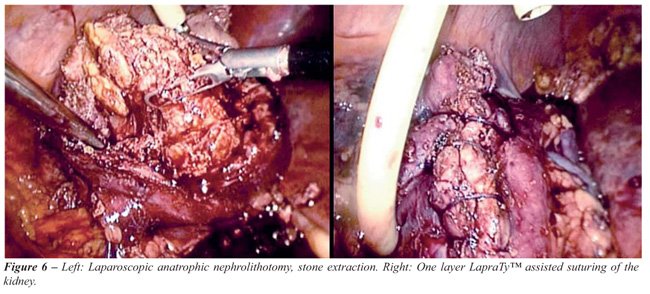

Laparoscopic

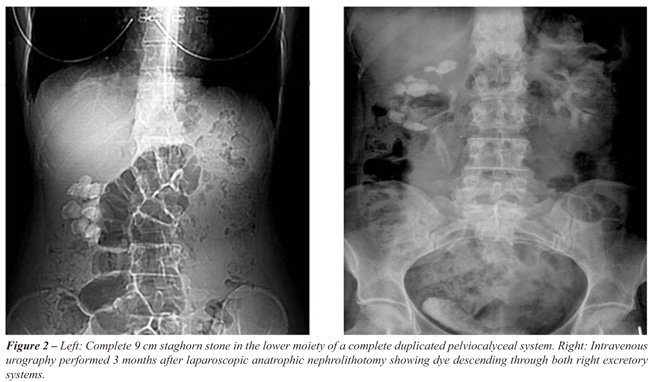

Anatrophic Nephrolithotomy

The kidney is dissected from the surrounding

fat, the vascular elements identified and clamped en bloc with a laparoscopic

Satinsky clamp. The renal parenchyma and collecting system are incised

longitudinally on the postero-lateral aspect of the kidney; the staghorn

stone is mobilized with graspers, removed and placed in an endobag. A

16 F Foley catheter is placed as a nephrostomy tube by making a small

incision in the kidney away from the nephrotomy line. The kidney is sutured

with a running 2/0 polyglactin single layer that includes renal capsule,

parenchyma, and collecting system in a “no-knot” technique

with the aid of Lapra-Ty clips (Ethicon-Johnsons & Johnsons), Figure-6.

RESULTS

Mean

age at surgery was 36 years (range 18-56), ASA score 2 (range 1-2), and

average number of stones removed was 12 (range 3 to 214). Laparoscopic

pyeloplasty combined with pyelolithotomy and flexible nephroscopy was

performed in ten patients, laparoscopic pyeloplasty with pyelolithotomy

and endoscopic-assisted nephrolithotomy was performed in two; and laparoscopic

anatrophic nephrolithotomy was performed in one patient (Table-2).

A double J stent and percutaneous drain

was left postoperatively in all patients. Additionally, a nephrostomy

drain using a 16 Fr Foley catheter was placed in two patients. All the

procedures were completed laparoscopically with no conversions to open

surgery. Intraoperative complications included two patients with lost

stones in the abdomen diagnosed during follow up (Figure-7) and variable

degrees of irrigation fluid accumulation secondary to nephroscopy in several

others. One patient had a postoperative urinary leak in the context of

an indwelling double J stent, which was not replaced at the time of surgery,

and most probably chronically obstructed. Leakage was discovered during

early postoperative period as urinary extravasation through the percutaneous

drain. Cystoscopic replacement of the double J stent effectively treated

the complication and the patient was discharged during the following days

without evidence of further leakage.

Stone free status was obtained in ten patients

(77%), and the remaining three were rendered stone free after one ancillary

procedure (shockwave lithotripsy - SWL) in two patients and retrograde

nephroscopy in another).

In all twelve patients with UPJ obstruction

the pyeloplasty was considered successful according to clinical (disappearance

of pain) and diuretic renal scan parameters. The mean washout half-life

time in the diuretic renal scan improved from 43 to 22 minutes.

Warm ischemia time for laparoscopic anatrophic

nephrolithotomy was 43 minutes; the patient was rendered stone free and

renal function remained within preoperative values.

COMMENTS

Endourology

has revolutionized the treatment of urinary stones. Notwithstanding, underlying

anatomic anomalies, extremely large stone burdens or a combination of

them can significantly decrease the success rate of endourological procedures

(3,4). The surgical approach in these special cases should efficiently

address the large stone burden and associated malformations in a single

procedure. Although open surgery is an alternative, laparoscopic surgery

might be a feasible option additionally conferring the advantages of minimally

invasive surgery.

Micali et al. reported 17 patients who underwent

laparoscopic stone extraction, including 11 with renal calculi and 9 with

associated anomalies (UPJ obstruction) with stone size up to 6 cm; fifteen

patients were eventually rendered stone free and one patient had a postoperative

urinoma. These authors concluded that indications for laparoscopy included

stones associated with anatomical abnormalities requiring reconstruction

and calculi for which endourological procedures had failed (5). Ramakumar

et al. reported 90% three month stone-free rate in 19 patients who underwent

laparoscopic pyelolithotomy and pyeloplasty (6). Similar results were

recently reported by Srivastava et al. (7) and Stein et al. (8) with 75

and 80% stone-free rates respectively.

Nambirajan et al. reported their experience

with eighteen patients who underwent different laparoscopic procedures

with concomitant stone removal, including pyeloplasties, partial nephrectomies,

and calyceal ablations. Stone-free status was achieved in 93% of cases.

The authors concluded that laparoscopy is effective for complex renal

stones and that the need for open surgery should be rare in the future

(9). Meria et al. compared laparoscopic pyelolithotomy to percutaneous

nephrolithotomy (PNL) in 32 patients with pelvic stones without underlying

malformations. Stone free rates were not significantly different (88 vs.

82%). However, the laparoscopic group had higher operative time, urological

complications (12% urine leak), and conversion to open surgery was required

in two patients. They concluded that indications for each technique must

be determined although PNL remains the gold standard for large pelvic

stones (10). It is our belief and current practice that SWL, retrograde

and percutaneous techniques are the first approaches to treat kidney stones

due to their excellent results and minimal morbidity. The role of laparoscopy

is not to replace any of these options, but to compliment them in situations

where decreased success or increased morbidity is expected, specially

as regards large stone burdens coexisting with underlying malformations.

As showed in our series and as reported by other authors (11,12), laparoscopic

and endourological techniques can be successfully combined in the same

procedure to improve the stone free rate and simultaneously resolve synchronous

anomalies.

Tunc et al. published a study on 150 patients

with stones in anomalous kidneys treated with SWL, including 57 duplex,

45 horseshoes, 30 malrotated, 14 pelvic, and 4 crossed ectopic. The overall

stone-free rate was 68%, with the worst results obtained in crossed ectopic

kidneys with stone clearance of only 25% (13). Pure percutaneous approach

has also been reported in anomalous kidneys. Although highly effective

with an overall stone-free rate of 83%, the anterior displacement of the

collecting system together with an unpredictable vascular supply and interposition

of bowel between the kidney and the abdominal wall makes the procedure

technically demanding. Moreover, it requires a highly precise imaging

system (i.e. CT guided) to minimize risk of visceral damage during kidney

puncture and tract creation (14). Pure endoscopic management has also

been accomplished for anomalous kidneys. Weizer et al. reported a 75%

stone-free rate (15), meanwhile Braz et al. reported an 81% stone-free

rate at three months, however 62% required ancillary treatments (16).

Due to urinary stasis, these patients suffer from poor spontaneous stone

passage, with persistence or growth of residual fragments in 60% of cases.

Laparoscopic techniques seem especially

useful for stones located in anomalous kidneys. Our overall stone-free

rate was 77% (10/13), and reached a 100% after one ancillary treatment

(i.e. SWL or nephroscopy). Additionally, anomalies to be addressed (i.e.

UPJ obstruction) were successfully repaired with optimal functional outcome.

There are several operative pitfalls that

need special consideration when combining laparoscopy with endourological

procedures. The operating room and the space around the operating table

become limited when the laparoscopic and endourological towers need to

be brought to work simultaneously. The laser cart and endourological instrumentation

table pose additional ergonomic problems. One serious limitation is the

difficulty to obtain fluoroscopic images during stone removal. Introduction

of a C arm becomes a challenge in the described set-up and even if possible

the images obtained in the insufflated abdomen of a patient in lateral

decubitus are far from informative. Deflating the abdomen may improve

the imaging but is unpractical and time consuming, and even after this,

images are of poor quality due to patient position and free fluid in the

abdomen, thus seriously limiting the ability to identify small residual

stones.

Irrigating fluid that flows freely into

the abdomen during the nephroscopy is of some concern and might be a limiting

factor. Although some of it can be suctioned, still large quantities of

fluid accumulate and occupy the space of the pneumoperitoneum. As fluid

accumulates between bowel loops it cannot be directly aspirated. We overcame

this difficulty by placing the patient in a “head down” position

for two minutes, allowing the fluid to accumulate under the diaphragm

where it becomes easily aspirated with the laparoscopic suction.

Identifying stones inside obstructed calyces

can become a real challenge. Intraoperative ultrasound can be useful in

these situations (9) however; it poses additional restrictions to the

already cumbersome operative scenario. We found a solution relying on

“cut for the light” technique, where the light of the endoscope

marks the stone containing calyx and the location for the parenchymal

incision. In the two cases performed, the light of the endoscope precisely

delineated the place for the nephrotomy (Figure-5).

Kaouk et al. created a porcine model to

address the feasibility of laparoscopic anatrophic nephrolithotomy (17),

Deger et al. reported the first case in humans (18), and recently Simforoosh

et al. (19) reported their series of five patients, with 3/5 being rendered

stone-free. Interestingly, no postoperative urinary extravasation occurred

albeit no internal stent was placed. We performed a laparoscopic anatrophic

nephrolithotomy in a young patient with a duplex system and a complete

staghorn of the lower moiety with optimal results and no perioperative

complications. The kidney was repaired with one running suture including

parenchyma and collecting system with no postoperative urinary extravasation.

An interesting aspect of laparoscopic pyelolithotomy

concerns stones lost in the abdomen. It is not infrequent during retrieval

of multiple small stones to have them fall out of the renal pelvis or

the endobag, and locating them in the abdomen is challenging and time

consuming. There is no report in the urological literature regarding this

issue; however there are well described complications of lost stones in

the abdomen after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. They include intraperitoneal

and abdominal wall abscess, fistula, and prolonged fever (20). Regarding

the infectious status of struvite staghorn stones, lost stones should

remain of concern. However, two patients in our series had lost stones

in the abdomen and after completing more than two years of follow-up,

they remain completely asymptomatic.

We are aware of the limitations of this

paper, which consist of a small, retrospective series of patients. However,

considering the limited data published up to date we believe our experience

contributes to the developing of this novel and poorly studied approach.

CONCLUSIONS

Although classical endourological procedures should remain as the gold standard for the great majority of renal stones, however patients with large stone burdens and underlying malformations might benefit from a combined laparoscopic and endourological one procedure solution that deals with complex stone disease and repairs associated anomalies.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Matlaga BR, Assimos DG: Changing indications of open stone surgery. Urology. 2002; 59: 490-3; discussion 493-4.

- Alivizatos G, Skolarikos A: Is there still a role for open surgery in the management of renal stones? Curr Opin Urol. 2006; 16: 106-11.

- Grasso M, Conlin M, Bagley D: Retrograde ureteropyeloscopic treatment of 2 cm. or greater upper urinary tract and minor Staghorn calculi. J Urol. 1998; 160: 346-51.

- Semerci B, Verit A, Nazli O, Ilbey O, Ozyurt C, Cikili N: The role of ESWL in the treatment of calculi with anomalous kidneys. Eur Urol. 1997; 31: 302-4.

- Micali S, Moore RG, Averch TD, Adams JB, Kavoussi LR: The role of laparoscopy in the treatment of renal and ureteral calculi. J Urol. 1997; 157: 463-6.

- Ramakumar S, Lancini V, Chan DY, Parsons JK, Kavoussi LR, Jarrett TW: Laparoscopic pyeloplasty with concomitant pyelolithotomy. J Urol. 2002; 167: 1378-80.

- Srivastava A, Singh P, Gupta M, Ansari MS, Mandhani A, Kapoor R, et al.: Laparoscopic pyeloplasty with concomitant pyelolithotomy--is it an effective mode of treatment? Urol Int. 2008; 80: 306-9.

- Stein RJ, Turna B, Nguyen MM, Aron M, Hafron JM, Gill IS, et al.: Laparoscopic pyeloplasty with concomitant pyelolithotomy: technique and outcomes. J Endourol. 2008; 22: 1251-5.

- Nambirajan T, Jeschke S, Albqami N, Abukora F, Leeb K, Janetschek G: Role of laparoscopy in management of renal stones: single-center experience and review of literature. J Endourol. 2005; 19: 353-9.

- Meria P, Milcent S, Desgrandchamps F, Mongiat-Artus P, Duclos JM, Teillac P: Management of pelvic stones larger than 20 mm: laparoscopic transperitoneal pyelolithotomy or percutaneous nephrolithotomy? Urol Int. 2005; 75: 322-6.

- Fariña Pérez LA, Cambronero Santos J, Meijide Rico F, Zungri Telo ER: Laparoscopic pyelolithotomy in a pelvic kidney. Actas Urol Esp. 2004; 28: 620-3.

- Whelan JP, Wiesenthal JD: Laparoscopic pyeloplasty with simultaneous pyelolithotomy using a flexible ureteroscope. Can J Urol. 2004; 11: 2207-9.

- Tunc L, Tokgoz H, Tan MO, Kupeli B, Karaoglan U, Bozkirli I: Stones in anomalous kidneys: results of treatment by shock wave lithotripsy in 150 patients. Int J Urol. 2004; 11: 831-6.

- Matlaga BR, Shah OD, Zagoria RJ, Dyer RB, Streem SB, Assimos DG: Computerized tomography guided access for percutaneous nephrostolithotomy. J Urol. 2003; 170: 45-7.

- Weizer AZ, Springhart WP, Ekeruo WO, Matlaga BR, Tan YH, Assimos DG, et al.: Ureteroscopic management of renal calculi in anomalous kidneys. Urology. 2005; 65: 265-9.

- Braz Y, Ramon J, Winkler H: Ureterorenoscopy and holmium laser lithotripsy for large renal stone burden: A reasonable alternative to percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Eur Urol. 2005; (Suppl 4): 264. (Abstract 1047).

- Kaouk JH, Gill IS, Desai MM, Banks KL, Raja SS, Skacel M, et al.: Laparoscopic anatrophic nephrolithotomy: feasibility study in a chronic porcine model. J Urol. 2003; 169: 691-6.

- Deger S, Tuellmann M, Schoenberger B, Winkelmann B, Peters R, Loening SA: Laparoscopic anatrophic nephrolithotomy. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2004; 38: 263-5.

- Simforoosh N, Aminsharifi A, Tabibi A, Noor-Alizadeh A, Zand S, Radfar MH, et al.: Laparoscopic anatrophic nephrolithotomy for managing large staghorn calculi. BJU Int. 2008; 101: 1293-6.

- Memon MA, Deeik RK, Maffi TR, Fitzgibbons RJ Jr: The outcome of unretrieved gallstones in the peritoneal cavity during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A prospective analysis. Surg Endosc. 1999; 13: 848-57.

____________________

Accepted after revision:

October 24, 2008

_______________________

Correspondence address:

Dr. Oscar Schatloff

Department of Urology

The Chaim Sheba Medical Center

Tel Hashomer, 52621, Israel

Fax: + 972 3 535-1892

E-mail: oscar.schatloff@gmail.com

EDITORIAL COMMENT

Authors

present interesting series of patients with urinary stone disease managed

mainly by laparoscopic method. The presented cases have some kind of anomaly

necessitating laparoscopic approach rather than using routine endourological

procedures like percutaneous nephrostolithotomy or urethroscopic means.

Laparoscopy is gaining more popularity in

managing urinary stone disease (1-3). This is especially true when associated

anomalies like ureteropelvic junction obstruction, or fusion anomalies

exists (4).

Even though results of laparoscopic approach

in managing stone disease in the present series and other reported series

seems satisfactory (1-5), longer follow-up and more cases are necessary

to better elucidate the exact role of laparoscopy in today’s management

of stone disease.

REFERENCES

- Simforoosh N, Aminsharifi A, Tabibi A, Noor-Alizadeh A, Zand S, Radfar MH, et al.: Laparoscopic anatrophic nephrolithotomy for managing large staghorn calculi. BJU Int. 2008; 101: 1293-6.

- Basiri A, Simforoosh N, Ziaee A, Shayaninasab H, Moghaddam SM, Zare S: Retrograde, antegrade and laparoscopic approaches for the management of large, proximal stones: A randomized clinical trial. J Endourol. 2008; 22: 2677-80.

- Meria P, Milcent S, Desgrandchamps F, Mongiat-Artus P, Duclos JM, Teillac P: Management of pelvic stones larger than 20 mm: laparoscopic transperitoneal pyelolithotomy or percutaneous nephrolithotomy? Urol Int. 2005; 75: 322-6.

- Mosavi-Bahar SH, Amirzargar MA, Rahnavardi M, Moghaddam SM, Babbolhavaeji H, Amirhasani S: Percutaneous nephrolithotomy in patients with kidney malformations. J Endourol. 2007; 21: 520-4.

- Simforoosh N, Basiri A, Danesh AK, Ziaee SA, Sharifiaghdas F, Tabibi A, et al.: Laparoscopic management of ureteral calculi: a report of 123 cases. Urol J. 2007; 4: 138-41.

Dr.

Nasser Simforoosh

Shaheed Labbafinejad Hospital

Urology Nephrology Research Center

Shaheed Beheshti University of Medical Sciences

Tehran, Iran

E-mail: simforoosh@iurtc.org.ir

EDITORIAL COMMENT

Laparoscopy

is an established modality in management of renal stones in selected situations.

On most occasions, laparoscopy is nephron sparing - namely - pyelolithotomy

as compared with percutaneous nephrostolithotomy (PCNL).

The authors have successfully used laparoscopy

combined with endourological procedures in anomalous kidneys, mainly ureteropelvic

junction obstruction. This is a retrospective study. Larger and prospective

studies will help in developing concrete guidelines.

It is to be noted that a renal angiogram

or CT angiogram is a complimentary investigation in planning reconstructive

laparoscopic surgery in anomalous kidneys.

The authors have not done an infundibuloplasty

in cases of infundibular stenosis with calyceal diverticulum and; the

collecting system was not closed separately in patients with staghorn

calculus where an anatrophic pyelolithotomy was done. It would be interesting

to see the configuration of the collecting system using a CT scan during

follow-up.

In most centers, pyeloplasty is done with

interrupted sutures. The authors have used running sutures for the anterior

and posterior walls.

Meria et al. had shown similar results with

different modalities (PCNL and laparoscopy) in management of stone disease

in non-anomalous kidneys; however the complication rate in was higher

in laparoscopy compared to ESWL and PCNL. Hence, they concluded that ESWL

or PCNL should be the first option in non-anomalous kidneys.

Practical problems of C arm usage; ultrasound

usage and free flow of irrigating fluid into the peritoneal cavity with

laparoscopy are problems to be looked into.

Combining laparoscopy with PCNL and pure

endoscopy gives a better result in stone disease.

Dr.

Manickam Ramalingam

Department of Urology

K.G. Hospital and Post Graduate Institute

Coimbatore, India

E-mail: uroram@yahoo.com