CURRENT

DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT OF SYRINGOCELE: A REVIEW

(

Download pdf )

doi: 10.1590/S1677-55382010000100002

JONATHAN MELQUIST, VIDIT SHARMA, DANIELLA SCIULLO, HEATHER MCCAFFREY, S. ALI KHAN

Department of Urology, SUNY at Stony Brook Medical Center, Stony Brook, New York, USA

ABSTRACT

Cowper’s syringocele is a rare but an under-diagnosed cystic dilation of the Cowper’s ducts and is increasingly being recognized in the adult population. Recent literature suggests that syringoceles be classified based on the configuration of the duct’s orifice to the urethra, either open or closed, as this also allows the clinical presentations of 2 syringoceles to be divided, albeit with some overlap. Usually post-void dribbling, hematuria, or urethral discharge indicate open syringocele, while obstructive symptoms are associated with closed syringoceles. As these symptoms are shared by many serious conditions, a working differential diagnosis is critical. Ultrasonography coupled with retro and ante grade urethrography usually suffices to diagnose syringocele, but supplementary procedures - such as cystourethroscopy, computed tomography scan, and magnetic resonance imaging - can prove useful. Conservative observation is first recommended, but persistent symptoms are usually treated with endoscopic marsupialization unless contraindicated. Upon reviewing the literature, this paper addresses the clinical anatomy, classification, presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of syringoceles in further detail.

Key

words: Cowper’s glands; dilation; urethral obstruction;

perineum; urinary incontinence

Int Braz J Urol. 2010; 36: 3-9

INTRODUCTION

Cowper’s syringocele is an uncommon but an under-diagnosed cystic dilation of the Cowper’s gland ducts. Syringoceles are traditionally viewed as a rare condition afflicting the pediatric population but are increasingly being recognized in the adult population. They are frequently not detailed in major uropathology, radiology, and urologic textbooks even though they can cause severe lower urinary tract symptoms by compressing the urethra or diverting urinary flow. This paper reviews the current literature on the clinical anatomy, classification, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment of syringoceles.

FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY OF COWPER’S GLANDS AND DUCTS

Cowper’s glands are composed of two exocrine structures located in the deep perineal pouch between fascial layers of the urogenital diaphragm. They excrete pre-ejaculate into the genito-urinary tract (1). The glands are composed of lobules made of epithelial cells aligned in acinar formation that secrete into the arborized collecting system. The glands eventually form two collecting ducts that measure on average 2.5 cm each. Although anatomic variations exist, the majority of ducts combine to make one confluent passage that opens at the posterior aspect of the bulbous urethra (2,3).

CLINICAL MANIFESTATION

AND CLASSIFICATION OF SYRINGOCELES

The

true prevalence of Cowper’s syringocele is unknown. It is thought

to be more pronounced in the pediatric population perhaps because symptoms

are appreciated preferentially at a younger age. However, there is a growing

body of literature suggesting the problem exists notably in the adult

population as well. There are at least 10 case reports describing this

rare anomaly in patients over the age of 18 (4).

Traditionally, Cowper’s syringocele

has been divided into four types: 1) simple syringocele with a modestly

dilated duct; 2) perforated syringocele with patulous communication with

the urethra; 3) imperforate syringocele with a dilated bulbous duct; 4)

ruptured syringocele that leaves its covering membrane in the urethra

often acting in a “ball-on-chain” fashion to cause obstruction

(5). Based on building luminal pressures within the ducts, syringoceles

may follow a standard maturation from simple to imperforate to either

perforated or ruptured, but more data is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Recent review suggests, however, that syringoceles should be grouped based

on the configuration of the duct’s orifice to the urethra, as this

also allows the clinical presentations of syringoceles to be divided (Table-1).

For instance, closed syringoceles have cystically occluded ducts that

cause the duct to dilate externally against the urethra and cause obstructive

symptoms. Open syringoceles have a continuous lumen between the urethra

and the cystic ducts, mimicking a urethral saccule and manifesting as

post-void dribbling (6-8). Obstructive symptoms may also manifest in open

syringoceles if the remnant membrane is oriented in the urethra to impede

flow. Furthermore, grouping syringoceles into these categories accounts

for the 4 categories of Maizel’s et al., since simple, perforated,

and ruptured syringoceles merge into open syringoceles and imperforate

syringoceles are classified as closed.

A review of 15 consecutive children with

Cowper’s syringocele proposed a similar simplified classification.

It classified two variants: non-obstructing syringoceles and obstructing

syringoceles. All of the non-obstructing syringoceles presented with a

combination of urinary tract infection (UTI), fever, and/or urinary incontinence.

All of the obstructing syringoceles had obstructive voiding symptoms or

ultrasonographic evidence of obstruction (9).

Hematuria, dysuria, frequency, and recurrent

UTI have also been associated with both categories of manifestation (10,11).

In one of the largest case reviews reported on adult syringoceles, six

of seven patients had open syringoceles, five of seven patients had a

history of UTI, six of seven had bloody urethral discharge, and five of

seven have post-void dribbling (6).

Since the symptoms of syringocele (Table-1)

are non-specific, a number of possibly more serious conditions can be

at play. The functional differential diagnosis upon history and physical

examination is urethral web, urethral duplication, anterior urethral valve,

anterior urethral diverticulum, congenital narrowing of bulbar urethra

- Cobb’s collar, urethral stricture, hydrocele (12), megalourethra,

periurethral abscess, perianal abscess, congenital urethral folds, prolapsed

posterior urethral valve, urethral tumors, urethral stones (13-19).

DIAGNOSIS

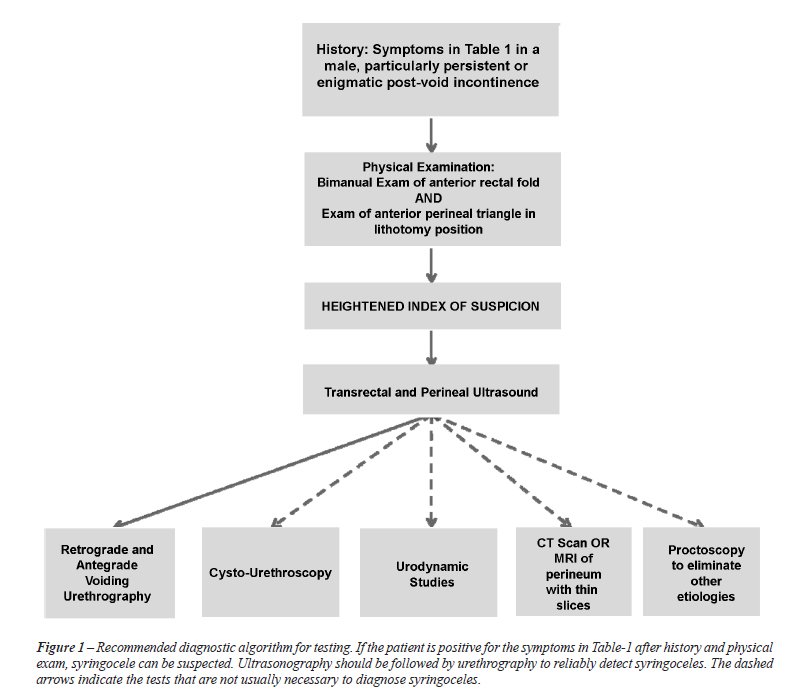

The initial evaluation of Cowper’s syringocele typically involves a thorough voiding history. A high index of suspicion justifies non-invasive imaging. Ultrasonography (US) sometimes visualizes closed cystic lesions in the anatomic region of Cowper’s gland (20-22). US has even been used to diagnose open syringocele. In one case report, a retrograde urethrogram was positive for large outpouching and sonourethrogram confirmed the cystic outpouchings when the urethra was distended with normal saline (4). To confirm or question US results the diagnosis should proceed with antegrade and retrograde urethrography, as this step is usually diagnostic (23). In case urethrography is contraindicated or more data is needed, cystourethroscopy, urodynamic studies, computed tomography (CT) scan, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be implemented. A proctoscopy may serve to shorten the differential diagnosis. This diagnosis algorithm is illustrated in Figure-1, and Table-2 addresses the indications for syringocele in the respective interventions.

Symptomatic, closed syringoceles often have

abnormal retrograde and voiding cystourethrograms. They can present as

a cystic filling defect distal to any potential prostatic obstruction.

The radiologic finding can be corroborated by uroflowometry that indicates

obstructive voiding rates (24). Cystourethroscopy sometimes detects an

abnormal protrusion from posterior wall of the bulbous urethra, raising

the index-of-suspicion for closed syringocele.

However, open syringoceles often can present

with simultaneous dysuria and post-void dribbling. They too can have an

obstructive pattern if the membranous flap acts in a “ball-and-chain”

fashion to cause transient urethral obstruction. Cystourethrogram can

be non-diagnostic but may indicate obstruction and/or cavernous filling

in adjacent urethral structure. Cystourethroscopy often reveals a defect

in the continuity of the posterior bulbous urethral wall, a remnant piece

of cystic wall, and/or a dilated luminal orifice (25).

MRI is a non-invasive diagnostic modality

continuing to define itself in diagnosis and management of Cowper’s

syringocele. It is found to be of particular benefit in evaluation of

closed syringoceles and has been successfully applied to both the adult

and pediatric population (26,27). MRI has supplanted CT due to its higher

soft-tissue resolution; nonetheless CT still has a diagnostic role especially

when MRI is contraindicated (28).

TREATMENT OF SYRINGOCELES

Asymptomatic

syringoceles are often observed (25). Although many symptomatic ones eventually

require surgical intervention, a trial period of conservative management

seems prudent, as spontaneous resolution of symptoms over time is not

uncommon. Bevers et al. have described several cases of confirmed both

open and closed syringoceles whose symptoms resolved on their own. One

case resolved after successful treatment for a UTI; others resolved with

no intervention (6).

In recent years endoscopic intervention has become the preferred intervention

for symptomatic syringocele’s. Typically unroofing the cyst by removing

its visage to the urethra is a simple, effective way of marsupialization

for both open and closed syringoceles. In Bevers et al. case series, all

four patients who went this urethroscopic intervention had complete resolution

of their symptoms with a maximum follow-up interval of 23 months (mean

12 months) (6). Unroofing typically uses a cold-knife; however, the Holmium:

YAG laser was successfully used in one case report (29).

Alternatively, open procedures such as transperineal ligation of the Cowper’s

duct are performed but are usually secondary to failed unroofing (30).

Open excision may be of benefit when the syringocele presents as a large

perineal mass (31). Laparoscopic excision-ligation of Cowper’s gland

has been described as another treatment modality and may be of benefit

but no trial has born this out (32).

The pediatric population can be treated with transurethral endoscopic

unroofing as well. However, current opinion recommends open intervention

for certain populations, such as children with large diverticula and inadequate

spongiosum. In such cases, diverticulectomy should be considered (9,33-35).

In the infant population where severe reflux exists due to an anterior

urethral valve phenomenon secondary to syringocele, urinary diversion

and vesicostomy should be considered (36,37).

CONCLUSION

Clinically it is more convenient to classify the cystic dilation of the Cowper’s Gland ducts as either open or closed, in terms of communication with the urethra, than the older system proposed by Maizels et al. The symptoms of the two types of syringocele can be categorized, albeit with some overlap. Usually post-void dribbling, hematuria, or urethral discharge indicates open syringocele, while obstructive symptoms are associated with closed syringoceles. As these symptoms are shared by many serious conditions, a working differential diagnosis is critical. Once the index of suspicion is established, transrectal and perineal US followed by retrograde and antegrade urethrography can effectively diagnose syringoceles. Other diagnostic technologies, such as cystourethroscopy, urodynamic studies, CT scan, and MRI, may be used to attain supplemental data. Treatment of the lesion should first proceed conservatively under observation, as symptoms may spontaneously resolve. Persistent symptoms are the benchmark for intervention, and endoscopic marsupialization has become the standard treatment for both open and closed syringocele, but open ligation-excision may be indicated in children. Although the success rates are high for syringocele diagnosis and treatment, more comparative data is essential for establishing standard protocols.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Chughtai B, Sawas A, O’Malley RL, Naik RR, Ali Khan S, Pentyala S: A neglected gland: a review of Cowper’s gland. Int J Androl. 2005; 28: 74-7.

- Masson JC, Suhler A, Garbay B: Cowper’s canals and glands. Pathological manifestations and radiologic aspects. J Urol Nephrol (Paris). 1979; 85: 497-511.

- Sanders MA: William Cowper and his decorated copperplate initials. Anat Rec B New Anat. 2005; 282: 5-12.

- Kumar J, Kumar A, Babu N, Gautam G, Seth A: Cowper’s syringocele in an adult. Abdom Imaging. 2007; 32: 428-30.

- Maizels M, Stephens FD, King LR, Firlit CF: Cowper’s syringocele: a classification of dilatations of Cowper’s gland duct based upon clinical characteristics of 8 boys. J Urol. 1983; 129: 111-4.

- Bevers RF, Abbekerk EM, Boon TA: Cowper’s syringocele: symptoms, classification and treatment of an unappreciated problem. J Urol. 2000; 163: 782-4.

- Sant GR, Kaleli A: Cowper’s syringocele causing incontinence in an adult. J Urol. 1985; 133: 279-80.

- Shintaku I, Ono Y, Katoh N, Takeda A, Ohshima S: Anterior urethral diverticulum produced by Cowper’s gland duct cyst. Int J Urol. 1996; 3: 412-3.

- Campobasso P, Schieven E, Fernandes EC: Cowper’s syringocele: an analysis of 15 consecutive cases. Arch Dis Child. 1996; 75: 71-3.

- Awakura Y, Nonomura M, Fukuyama T: Cowper’s syringocele causing voiding disturbance in an adult. Int J Urol. 2000; 7: 340-2.

- Månsson W, Colleen S, Holmberg JT: Cystic dilatation of Cowper’s gland duct--an overlooked cause of urethral symptoms? Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1989; 23: 3-5.

- Marte A, Prezioso M, Sabatino MD, Borrelli M, Romano M, Del Balzo B, et al.: Syringocele in children: an unusual presentation as scrotal mass. Minerva Pediatr. 2009; 61: 123-7.

- Vega RE: Distal urethral web: a risk factor in prostatitis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2002; 5: 180-2.

- Zugor V, Schreiber M, Labanaris AP, Weissmüller J, Wullich B, Schott GE: Urethral duplication: long-term results for a rare urethral anomaly. Urologe A. 2008; 47: 1603-6.

- Myers RP, Cahill DR, Kay PA, Camp JJ, Devine RM, King BF, et al.: Puboperineales: muscular boundaries of the male urogenital hiatus in 3D from magnetic resonance imaging. J Urol. 2000; 164: 1412-5.

- Kajbafzadeh A: Congenital Urethral Anomalies in Boys. Part II. Urol J. 2005; 2: 125-131.

- Mutlu N, Culha M, Mutlu B, Acar O, Turkan S, Gokalp A: Cobb’s collar and syringocele with stone. Int J Clin Pract. 1998; 52: 352-3.

- Dewan PA: A study of the relationship between syringoceles and Cobb’s collar. Eur Urol. 1996; 30: 119-24.

- Dewan PA, Keenan RJ, Morris LL, Le Quesne GW: Congenital urethral obstruction: Cobb’s collar or prolapsed congenital obstructive posterior urethral membrane (COPUM). Br J Urol. 1994; 73: 91-5.

- Strasser H, Frauscher F, Klauser A, Mitterberger M, Pinggera GM, Rehder P, et al.: Transrectal three dimensional sonography. Techniques and indications. Urologe A. 2004; 43: 1371-6.

- Pavlica P, Barozzi L, Stasi G, Viglietta G: Ultrasonography in syringocele of the male urethra (ultrasound-urethrography). Radiol Med. 1989; 78: 348-50.

- Yagci C, Kupeli S, Tok C, Fitoz S, Baltaci S, Gogus O: Efficacy of transrectal ultrasonography in the evaluation of hematospermia. Clin Imaging. 2004; 28: 286-90.

- Watson RA, Lassoff MA, Sawczuk IS, Thame C: Syringocele of Cowper’s gland duct: an increasingly common rarity. J Urol. 2007; 178: 285.

- Richter S, Shalev M, Nissenkorn I: Late appearance of Cowper’s syringocele. J Urol. 1998; 160: 128-9.

- Campobasso P, Schieven E, Sica F: Cowper’s syringocele in children: report on ten cases. Minerva Pediatr. 1995; 47: 297-302.

- Selli C, Nesi G, Pellegrini G, Bartoletti R, Travaglini F, Rizzo M: Cowper’s gland duct cyst in an adult male. Radiological and clinical aspects. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1997; 31: 313-5.

- Kickuth R, Laufer U, Pannek J, Kirchner TH, Herbe E, Kirchner J: Cowper’s syringocele: diagnosis based on MRI findings. Pediatr Radiol. 2002; 32: 56-8.

- Merchant SA, Amonkar PP, Patil JA: Imperforate syringoceles of the bulbourethral duct: appearance on urethrography, sonography, and CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997; 169: 823-4.

- Piedrahita YK, Palmer JS: Case report: Cowper’s syringocele treated with Holmium:YAG laser. J Endourol. 2006; 20: 677-8.

- Santin BJ, Pewitt EB: Cowper’s duct ligation for treatment of dysuria associated with Cowper’s syringocele treated previously with transurethral unroofing. Urology. 2009; 73: 681.e11-3.

- Redman JF, Rountree GA: Pronounced dilatation of Cowper’s gland duct manifest as a perineal mass: a recommendation for management. J Urol. 1988; 139: 87-8.

- Cerqueira M, Xambre L, Silva V, Prisco R, Santo R, Lages R, et al.: Imperforate syringocele of the Cowper’s glands laparoscopic treatment. Actas Urol Esp. 2004; 28: 535-8.

- McLellan DL, Gaston MV, Diamond DA, Lebowitz RL, Mandell J, Atala A, et al.: Anterior urethral valves and diverticula in children: a result of ruptured Cowper’s duct cyst? BJU Int. 2004; 94: 375-8.

- Oesch I, Kummer M, Bettex M: Congenital urethral diverticula in boys. Eur Urol. 1983; 9: 139-41.

- Kaneti J, Sober I, Bar-Ziv J, Barki Y: Congenital anterior urethral diverticulum. Eur Urol. 1984; 10: 48-52.

- Rushton HG, Parrott TS, Woodard JR, Walther M: The role of vesicostomy in the management of anterior urethral valves in neonates and infants. J Urol. 1987; 138: 107-9.

- Van Savage JG, Khoury AE, McLorie GA, Bägli DJ: An algorithm for the management of anterior urethral valves. J Urol. 1997; 158: 1030-2.

____________________

Accepted after revision:

August 31, 2009

_______________________

Correspondence address:

Dr. S. Ali Khan

Professor of Urology

HSC level 9, room 040

SUNY at Stony Brook

New York, 11794-8093, USA

Fax: + 1 631 444-7621

E-mail: saakhan@notes.cc.sunysb.edu

EDITORIAL COMMENT

Keep in

mind the possibility of syringocele diagnosis is the greatest message

by Melquist et al. in this article. The authors conducted an excellent

review about this disease, unknown by many urologists. Usually identified

in the pediatric population, its occurrence has been increasingly reported

in adults as well. Once it shares its symptoms with a variety of other

urinary tract diseases, auxiliary methods of diagnosis are required. However,

the lack of comparative studies between different imaging methods does

not allow a definitive conclusion about the most effective one. Despite

the higher cost, MRI adds the greatest amount of information, useful not

only for diagnosis but also for the therapeutic decisions to be taken.

Among the invasive methods, urethroscopy is the confirmatory procedure.

Another important aspect highlighted in this review was the possibility

to simplify the syringocele classification in only two types - non-obstructing

syringoceles and obstructing syringoceles. Such categorization allows

a better understanding of its physiopathology, as well as, suggesting

the appropriate treatment.

There is limited international published literature about syringocele

and this review should encourage urologists to the search for this diagnosis

as a differential possibility for bladder outlet obstruction and recurrent

urinary tract infections.

You need to know the disease before you can identify it.

Dr.

José Carlos Truzzi

Section of Urology

Federal University of Sao Paulo, UNIFESP

Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil

E-mail:jctruzzi@hotmail.com