LEARNING

CURVE FOR RADICAL RETROPUBIC PROSTATECTOMY

(

Download pdf )

Clinical Urology

Vol. 37 (1): 67-78,

January - February, 2011

doi: 10.1590/S1677-55382011000100009

FERNANDO J. A. SAITO, MARCOS F. DALL’OGLIO, GUSTAVO X. EBAID, HOMERO BRUSCHINI, DAHER C. CHADE, MIGUEL SROUGI

Division of Urology, University of Sao Paulo Medical School and Cancer Institute, State of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Purpose:

The learning curve is a period in which the surgical procedure is performed

with difficulty and slowness, leading to a higher risk of complications

and reduced effectiveness due the surgeon’s inexperience. We sought

to analyze the residents’ learning curve for open radical prostatectomy

(RP) in a training program.

Materials and Methods: We conducted a prospective

study from June 2006 to January 2008 in the academic environment of the

University of São Paulo. Five residents operated on 184 patients

during a four-month rotation in the urologic oncology division, mentored

by the same physician assistants. We performed sequential analyses according

to the number of surgeries, as follows: = 10, 11 to 19, 20 to 28, and

= 29.

Results: The residents performed an average

of 37 RP each. The average psa was 9.3 ng/mL and clinical stage T1c in

71% of the patients. The pathological stage was pT2 (73%), pT3 (23%),

pT4 (4%), and 46% of the patients had a Gleason score 7 or higher. In

all surgeries, the average operative time and estimated blood loss was

140 minutes and 488 mL. Overall, 7.2% of patients required blood transfusion,

and 23% had positive surgical margins.

Conclusion: During the initial RP learning

curve, we found a significant reduction in the operative time; blood transfusion

during the procedures and positive surgical margin rate were stable in

our series.

Key

words: prostatic neoplasms; prostatectomy; learning; internship

and residency; postoperative complications

Int Braz J Urol. 2011; 37: 67-78

INTRODUCTION

Prostate

cancer (PCa) is currently the most common malignant tumor among men in

Europe and the United States (US), except for malignant non-melanoma skin

tumors. In the US, it is estimated that about 192,280 new cases are diagnosed

per year, with 27,360 deaths a year due to PCa, which represents 9% of

all cancer deaths in the country per year (1). In Europe, each year there

are an estimated 190,000 new cases, with more than 50,000 deaths from

the disease (2).

Radical prostatectomy (RP) was the first

widely used standard treatment for localized PCa. The classic approach

is the retropubic technique. RP was introduced in 1905 by Young and reviewed

by Millin in 1946. However, it only became routinely and safely performed

in 1982, when Walsh et al. published new technical aspects of the surgery,

definitely setting the surgical standards for the treatment of PCa (3).

Since then, new techniques and approaches have been developed, such as

perineal (4), laparoscopic (5,6) and robotic-assisted RP (7). Throughout

the first decade of the 21st century, the use of robotic-assisted surgery

has rapidly increased in the U.S. (1), spanning the last three years to

Europe (2) and finally to Brazil in 2008 (8).

Subsequently new technological elements

have been incorporated into the surgical technique of RP, and increasingly

high additional direct and indirect expenses have significantly added

to the total cost of the procedure. Notwithstanding

the problem of significantly elevated costs, technological complexity

incorporated into new techniques may result in a longer or yet unclear

learning curve (9).

High costs and a possibly longer learning

curve prompted us to question the applicability of these new surgical

modalities into clinical practice of our hospitals, especially those related

to the public health system of our country. Furthermore, there still lacks

a thorough discussion of their unclear benefits to oncologic outcomes

and quality of life of patients who undergo minimally invasive procedures

(10). To what extent have perineal, laparoscopic or robotic-assisted RP

proved superior to the open retropubic approach?

The learning curve in surgery can be defined

as the number of cases required to perform the procedure with reasonable

operating time and an acceptable rate of complications, resulting in an

adequate postoperative clinical outcome associated with a shorter hospital

stay. Obviously, several key factors may impact the learning curve, not

only such as those related to the surgeon, as attitude, confidence, experience

with other surgical procedures, but also those related to the team members

involved in the procedures. Undoubtedly, the number of cases performed

by the surgeon and the volume of surgeries in a given center may certainly

delineate the course of surgical outcomes (11).

RP is a particularly complex surgical procedure

and it is assumed to be closely related to the surgical technique employed,

depending in part on the surgeon’s experience. Currently each RP

technique, either open (retropubic and perineal), or minimally invasive

(laparoscopic and robotic), present distinctive learning curves for the

surgeon.

Due to the wide variation in training formats

offered in the various surgical programs in urology, we sought to evaluate

the learning curve for open RP among third-year urology residents (fifth

year of residency in surgery overall) in a high volume tertiary referral

center. We aimed at both defining a minimum number of procedures necessary

to properly train the resident surgeon in urology for this procedure,

as well as on determining the most sensitive key points of the learning

process. As a result, we may be able to continuously improve the teaching

process of the surgical technique and make it widely available to mentors

and teaching centers, especially considering the social environment of

growing ethical concerns with patient safety.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We

conducted a prospective study from June 2006 to January 2008 in the urologic

oncology division of the University of São Paulo. Patients with

clinically localized prostate adenocarcinoma (cT1-2 Nx M0) with medical

conditions for surgical treatment were selected. Five residents operated

on 184 patients during a four-month rotation in the urologic oncology

division, mentored by the same physician assistants. Patients who had

undergone other treatments such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy or

biological agents prior or concomitant to surgery and patients with significant

neurological, psychiatric disorders, including dementia or seizures, were

excluded from the study.

Surgeries were performed following the same

surgical technique for radical retropubic prostatectomy, as previously

described (11,12). In all surgeries, the residents were assisted by 5

attending surgeons. Fifteen days after hospital discharge, the indwelling

catheter and stitches were removed. The first functional evaluation (urinary

incontinence) was 60 days after surgery, as well as laboratory tests (PSA

value, blood count and serum creatinine).

The length of operative time was measured

from skin incision until the completion of the wound dressing. The estimated

blood loss was calculated by measuring the volume of the vacuum bottle

minus the amount of saline used during surgery. No sponges were used during

surgery.

We also assessed the surgical pathology

stage and Gleason score, in all cases, as well as positive surgical margin

for extracapsular extension. Statistical analysis was performed by using

analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the number of surgeries in quartiles:

up to 10, from 11 to 19, from 20 to 28 and more than 29 surgeries. Fisher’s

exact test was applied to evaluate the groups.

RESULTS

Each resident participated in the study during four consecutive months and, on average, each one of them performed 9 surgeries per month (Table-1).

The demographics of patients who underwent

RP are summarized in Table-2.

The surgical pathology stage, prostate size,

Gleason score and surgical margins are summarized in Table-3.

Table-4 presents surgical data. The median

operative time was 140 minutes, and most patients did not require blood

transfusion.

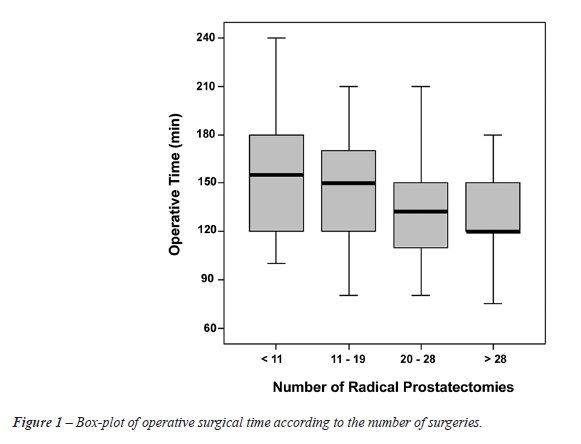

A curve of decreasing operative time (p

= 0.03) is shown in Figure-1, comparing the 19 initial RP to the following

9 RP performed (p = 0.01) and the remaining surgeries from 29 and more

(p < 0.001). From the twentieth RP onwards, we found a significant

decrease in the operative time.

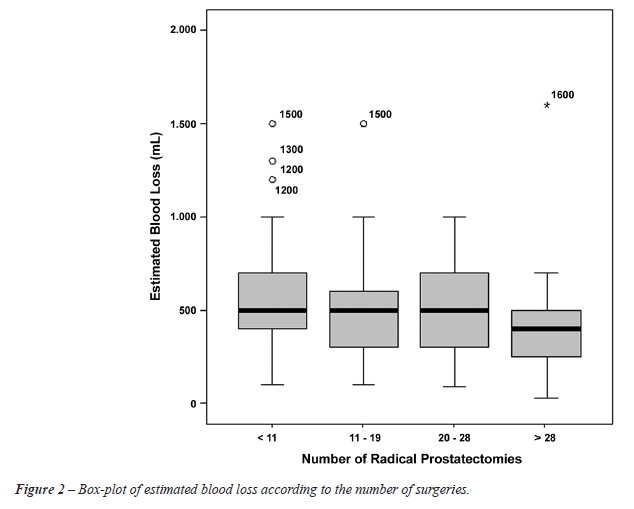

There was a progressive decrease in estimated

blood loss as the residents gained surgical experience with RP, as shown

in Figure-2.

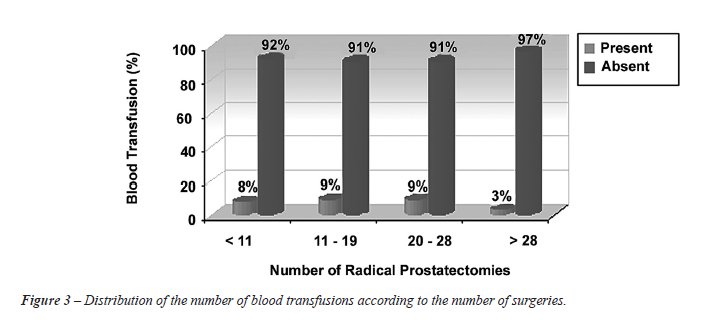

Figure-3 shows the association between the

number of surgeries performed and need for blood transfusion, where a

3% transfusion rate was observed after the 29th surgery.

When the resident operated on smaller prostates, blood transfusion was rarely required, as highlighted in Tables 5 and 6, where prostates < 40g and > 40g required a blood transfusion in 3% and 13% of RP, respectively.

In reviewing the occurrence of positive

surgical margins, we observed that it remained stable during the four

phases, as shown in Table-7.

COMMENTS

The

RP learning curve for residents showed that after twenty surgeries, there

was a significant reduction in operative time from 150 to 120 minutes

and, after the 29th surgery, the need for blood transfusion also decreased

from 9% to 3%. Moreover, the percentage of compromised surgical margins

remained stable during the learning curve.

The discussion regarding the learning curve

in RP has not been frequently addressed in clinical studies and few series

have reported clinical and pathologic data exclusively of residents in

training instead of only experienced surgeons (13,14). Published evidence

has demonstrated that the number of RP previously performed by the surgeon

affects patient outcomes. It is believed that a learning curve of 200

cases would be necessary to achieve an “expert” status (13,15).

A recent prospective study evaluated surgeons

after a urologic oncology fellowship program, after they had already completed

an initial learning curve of an average of 47 cases during residency and

another 87 RP performed during the fellowship (15). The mean operative

time was 201 minutes, the estimated blood loss was 734 mL, with a 6% rate

of blood transfusion.

The learning curve is a major problem in surgery, during which the surgical

procedure is usually performed with more difficulty and slowness, associated

with a higher risk of complications and low efficacy due to inexperience

of the surgeon. If an initial assessment is made, the learning curve is

primarily a theoretical concept, because this is a theme or line of research

rarely present in residency programs and urologic literature.

The surgeons gain much of the knowledge

necessary for surgical procedures during medical residency programs. In

the learning process, the urology resident trains in the areas of endourology,

incontinence and reconstruction, erectile dysfunction and infertility,

pediatric urology and kidney transplantation, laparoscopy and cryotherapy.

Within the urologic oncology division, several surgeries are performed,

such as transurethral resection of the prostate and bladder, cystectomy

and urinary reconstruction, retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy and open and

laparoscopic nephrectomy, fostering a growing field of surgical procedures

and greater confidence to perform them. The American Urological Association

reported that the number of RP performed by residents has declined in

recent years, and overall 84% of surgeons have performed less than ten

RP annually (8). Based on these data, we can infer that much of the surgical

experience needed to acquire proficiency in complex procedures can only

be acquired during residency. Eventually, according to local community

demand or the volume of surgeries performed at the hospital, this development

may never occur.

The percentage of compromised surgical margins

varies with the surgeon’s experience in this procedure. According

to a landmark study by Vickers et al., the rate of positive margins was

36% before 50 RP performed, 29% with 50 to 99 RP, 23% with 100 to 249

RP, 22% with 250 to 999 RP, and 11% with 1000 RP or more (16). Overall,

the surgical margin status was positive in 22.9% of surgeries.

Regarding minimally invasive RP techniques,

usually performed by surgeons in large centers with extensive surgical

experience, data on robotic and laparoscopic was as follows, respectively:

blood transfusion 3% and 9.8%, positive surgical margin of 15.8% and 19.5%,

mean operative time was 166 and 160 minutes, and average hospital stay

of 5.4 and 4.9 days (17). A study describing the learning curve of robotic

RP showed that the robotic surgeon with up to 12 surgeries had an average

operative time of 242 ± 64 minutes and 58% of cases with positive

margins; with 13 to 188 robotic RP, the operative time was reduced to

165 ± 45 minutes and positive margins to 23%. Surgeons who performed

more than 189 robotic RP had an average operative time of 134 ±

45 minutes and positive margins in 9% (18).

The following strengths can be highlighted

in the present study: a homogeneous group of residents in training who

had never performed a RP was included; the prospective design of the study

allowed us to perform the same surgical technique and mentored by the

same group of physician assistants; and the sample size accrued was reasonable.

Therefore, we believe that these results may generate important information

on surgical training and education in urologic oncology.

The fact that the surgeon is inexperienced,

starting the learning curve with this procedure, may be of benefit by

rapidly improving the performance in the short term, considering that

a homogenous and standardized teaching methodology is applied. As our

data suggests, it renders the possibility to generate less intraoperative

morbidity and lower rate of positive surgical margins, improving the clinical

course of patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Open radical prostatectomy is a safe and effective procedure that can be done on a large scale in teaching institutions, as long as a structured training program provides adequate teaching methods. During the initial training experience of a surgeon, a steep reduction in blood transfusions and a quick stabilization of the learning curve after twenty procedures can be expected.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ: Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225-49.

- Boyle P, Ferlay J: Cancer incidence and mortality in Europe, 2004. Ann Oncol. 2005; 16: 481-8.

- Walsh PC, Lepor H, Eggleston JC: Radical prostatectomy with preservation of sexual function: anatomical and pathological considerations. Prostate. 1983; 4: 473-85.

- Elder JS, Jewett HJ, Walsh PC: Radical perineal prostatectomy for clinical stage B2 carcinoma of the prostate. J Urol. 1982; 127: 704-6.

- Guillonneau B, Cathelineau X, Barret E, Rozet F, Vallancien G: Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: technical and early oncological assessment of 40 operations. Eur Urol. 1999; 36: 14-20.

- Abbou CC, Salomon L, Hoznek A, Antiphon P, Cicco A, Saint F, et al.: Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: preliminary results. Urology. 2000; 55: 630-4.

- Tewari A, Peabody J, Sarle R, Balakrishnan G, Hemal A, Shrivastava A, et al.: Technique of da Vinci robot-assisted anatomic radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2002; 60: 569-72.

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde: Estimativa 2008: incidência do câncer no Brasil. Instituto Nacional do Câncer. Brasília, DF; 2007.

- Shah A, Okotie OT, Zhao L, Pins MR, Bhalani V, Dalton DP: Pathologic outcomes during the learning curve for robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Int Braz J Urol. 2008; 34: 159-62; discussion 163.

- Frota R, Turna B, Barros R, Gill IS: Comparison of radical prostatectomy techniques: open, laparoscopic and robotic assisted. Int Braz J Urol. 2008; 34: 259-68; discussion 268-9.

- Srougi M, Nesrallah LJ, Kauffmann JR, Nesrallah A, Leite KR: Urinary continence and pathological outcome after bladder neck preservation during radical retropubic prostatectomy: a randomized prospective trial. J Urol. 2001; 165: 815-8.

- Srougi M, Paranhos M, Leite KM, Dall’Oglio M, Nesrallah L: The influence of bladder neck mucosal eversion and early urinary extravasation on patient outcome after radical retropubic prostatectomy: a prospective controlled trial. BJU Int. 2005; 95: 757-60.

- Eastham JA, Kattan MW, Riedel E, Begg CB, Wheeler TM, Gerigk C, et al.: Variations among individual surgeons in the rate of positive surgical margins in radical prostatectomy specimens. J Urol. 2003; 170: 2292-5.

- Andriole GL, Smith DS, Rao G, Goodnough L, Catalona WJ: Early complications of contemporary anatomical radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 1994; 152: 1858-60.

- Rosser CJ, Kamat AM, Pendleton J, Robinson TL, Pisters LL, Swanson DA, et al.: Impact of fellowship training on pathologic outcomes and complication rates of radical prostatectomy. Cancer. 2006; 107: 54-9.

- Vickers AJ, Bianco FJ, Serio AM, Eastham JA, Schrag D, Klein EA, et al.: The surgical learning curve for prostate cancer control after radical prostatectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007; 99: 1171-7.

- Rozet F, Jaffe J, Braud G, Harmon J, Cathelineau X, Barret E, et al.: A direct comparison of robotic assisted versus pure laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: a single institution experience. J Urol. 2007; 178: 478-82.

- Jaffe J, Castellucci S, Cathelineau X, Harmon J, Rozet F, Barret E, et al.: Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy: a single-institutions learning curve. Urology. 2009; 73: 127-33.

____________________

Accepted after revision:

May 25, 2010

_______________________

Correspondence address:

Dr. Marcos F. Dall’Oglio

Rua Barata Ribeiro, 398, 5º Andar

01308-000, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

Fax: + 55 11 3159-3618

E-mail: marcosdallogliouro@terra.com.br

EDITORIAL COMMENT

Open radical

prostatectomy is the gold standard and most widespread treatment for clinically

localized prostate cancer.

About thirty years ago the first purposeful nerve sparing radical prostatectomies

were performed by Dr. Patrick Walsh. Since then, a better understanding

of the periprostatic anatomical results with continued improvement in

functional outcomes and oncological control for patients undergoing radical

prostatectomy, whether by open or minimally-invasive surgery.

The oncologic results of author’s paper in an important center of

high volume treatment of prostate cancer are in line with those reported

with the use of the retropubic approach. With a “homogenous and

standardized teaching methodology”, the residents can achieve good

data as regards less intraoperative morbidity and lower rate of positive

surgical margins, improving the clinical course of patients.

The learning curve in surgery can be defined as the number of cases required

to perform the procedure with reasonable operating time and an acceptable

rate of complications, resulting in an adequate postoperative clinical

outcome associated with a shorter hospital stay (1).

A paper was published about the learning curve for surgery for prostate

cancer recurrence after radical prostatectomy. The study cohort included

7765 prostate cancer patients who were treated with radical prostatectomy

by one of 72 surgeons at four major US academic medical centers between

1987 and 2003. The learning curve for prostate cancer recurrence after

radical prostatectomy was steep and did not start to plateau until a surgeon

had completed approximately 250 prior operations (2). As a surgeon’s

experience increases, cancer control after radical prostatectomy improves.

These results may generate important information on surgical training,

improve the teaching process of the surgical technique and make it widely

available to mentors and teaching centers, especially considering the

social environment of growing ethical concerns with patient safety. Further

research is needed to examine the specific techniques used by experienced

surgeons that are associated with improved outcomes.

REFERENCES

- Vickers AJ, Bianco FJ, Serio AM, Eastham JA, Schrag D, Klein EA, et al.: The surgical learning curve for prostate cancer control after radical prostatectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007; 99: 1171-7.

- Vickers A, Bianco F, Cronin A, Eastham J, Klein E, Kattan M, et al.: The learning curve for surgical margins after open radical prostatectomy: implications for margin status as an oncological end point. J Urol. 2010; 183: 1360-5.

Dr. Mauricio

Rubinstein

Department of Urology

Federal University of Rio de Janeiro State

Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

E-mail: mrubins74@hotmail.com

EDITORIAL COMMENT

The learning

curve plateau comes with training and experience. Surgeons have always

recognized a structured way to introduce new procedures: learning a new

technique requires dedication.

If we try to define a learning curve, we should look back at the work

of Dr. Donald Ross - a pioneer in cardiac surgery in the United Kingdom

- who proposed the Ross procedure in 1962 (1). The Ross procedure, first

performed in 1967, is a challenging operation for patients with aortic

valve disease. The principle is to remove the patient’s normal pulmonary

valve and used it to replace the patient’s diseased aortic valve.

In Dr. Ross’s own series, 23% of the patients died during the first

year of the operation and 18% in the second year. The following 10 years,

surgical mortality in a series of 188 patients dropped to 9%. This is

a learning curve. The message: it requires time and hard work.

How many cases do we need to become expert surgeons in the technique we

perform on an everyday basis? The latter remain a controversial question

for the field of radical prostatectomy. The arrival of both, laparoscopy

and later robotic surgery has put on stage the term learning curve. In

fact, laparoscopic series brought with them a tremendous enthusiasm in

terms of validation of the technique and therefore extensive work in the

procedure’s learning curve.

In our experience at the Institut Montsouris in Paris, it was hard to

keep in mind Dr. Walsh’s concepts on radical prostatectomy and simultaneously

comply with the demanding endoscopic surgical environment, but a step-by-step

structured training brought us through the task.

The paper on the learning curve of retropubic radical prostatectomy presented

by Dall’Oglio et al. in this issue of IBJU, represents a comprehensive

analysis of the initial experience of a group of residents with retropubic

prostatectomy, perhaps missing in the literature. The paper offers real

information gained by surgical experience and presents a sincere vision

of a proctored prostatic surgical approach in the everyday world.

Dall’Oglio et al. found in their interesting analysis, that improvement

of clinical outcomes can be seen after 20 to 30 cases. We could say that

these findings are far from those presented by Vickers et al in their

timely publication assessing surgical learning curve for prostate cancer

control (2). Vickers et al. found statistical significance related to

surgeon’s experience and cancer control after radical prostatectomy

in an analysis of highly dedicated surgeons. This study brought back to

reality the definition of learning curve in radical prostatectomy, reflecting

a real link between surgical technique and cancer control, and establishing

the concept of a dramatic improvement in cancer control with increasing

surgeon experience up to 250 previous treated cases. That said, we must

agree with Dr. Stuart Howards in the fact that it is somewhat arbitrary

to assert that it is necessary to perform 250 procedures to become competent

and provide good cancer control (3). Therefore, establishing solid bases

for radical prostatectomy performed in a Urology program, is an important

challenge to any institution and it requires hard dedication and a focused

operating room team; but as presented in the Dall’Oglio et al. study

this is a feasible task and it might get the future urologists ready to

finish their training and be able to offer a surgical procedure of the

highest quality.

The future seems difficult for the young urologist, because as presented

by Ficarra et al., positive surgical margin rates decreased with the surgeon’s

experience and technique improvement, reaching similar percentages for

retropubic, laparoscopic and robotic series (4); but perhaps the positive

surgical margins are not so secure as oncological endpoint (5) and even

our current definitions for biochemical recurrences do not substantially

impact prognostic factor estimates. This situation implies that the training

period should provide solid concepts to build a professional career, and

because knowledge and concepts might and will change; an academic way

to learn, and eventually teach, is the way that it ought to be in order

to assure the adequate surgical treatment of patients, in years to come.

With a structured methodical system, it is possible to implement radical

prostatectomy safely and effectively without compromising morbidity, oncological

and functional outcomes. A team-based approach helps to reduce the learning

curve of the procedure for individual surgeons. This was our initial approach

for laparoscopic and robotic prostatectomy at our institution.

The fruit you harvest from the three in this interesting publication is

that we must be sure to teach the philosophy of how to adequately treat

localized prostate cancer and then, we must get in the operating room

with the urologists-in-training to provide them with the basic tools that

will hopefully sustain future reliable operators.

REFERENCES

- Ross DN: Homograft replacement of the aortic valve. Lancet. 1962; 2: 487.

- Vickers AJ, Bianco FJ, Serio AM, Eastham JA, Schrag D, Klein EA, et al.: The surgical learning curve for prostate cancer control after radical prostatectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007; 99: 1171-7.

- Howards S: Editorial comment. (Savage et Vickers. Low annual caseloads of United States surgeons conducting radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2009; 182: 2677-9). J Urol. 2009; 182: 2679-80; discussion 2681.

- Ficarra V, Cavalleri S, Novara G, Aragona M, Artibani W: Evidence from robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: a systematic review. Eur Urol. 2007; 51: 45-55; discussion 56.

- Vickers A, Bianco F, Cronin A, Eastham J, Klein E, Kattan M, et al.: The learning curve for surgical margins after open radical prostatectomy: implications for margin status as an oncological end point. J Urol. 2010; 183: 1360-5.

Dr. Rafael

Sanchez-Salas and

Dr. Francois Rozet

Department of Urology

Institut Montsouris

Université Paris Descartes

Paris, France

E-mail: francois.rozet@imm.fr

REPLY BY THE AUTHORS

Both editorial

comments reassured the importance of a structured learning methodology

in the surgical field and pointed out the feasibility of safely teaching

complex procedures, such as radical prostatectomy. In our study, we sought

to demonstrate a real learning curve of inexperienced surgeons, on which

we could evaluate both an increasing growth in surgical skills from an

early starting point, combined with the radical prostatectomy training

itself. This was possible due to a homogeneous group of mentors, all of

them with more than 200 prostatectomies performed.

As mentioned in the editorial, the landmark paper by Dr. Vickers demonstrated

a long learning curve, on which improvements were observed to 250 cases

performed (1). This study differed significantly from ours, since not

only no standardized surgical methodology was applied by all 72 surgeons,

but also several very experienced surgeons after urology training were

included in the study.

Although our learning curve demonstrated an initial experience with radical

prostatectomy, the standardized technique had been extensively improved

and validated by Prof. Miguel Srougi, throughout his 4,000 cases (2,3).

Currently, two participating residents in the study are now mentors of

the residents at our institution.

A further study is now being finalized and will focus on the initial 100

consecutive cases operated with this same standardized technique, with

a larger number of surgeons, due to the expansion of our program. Therefore,

we expect to generate a stronger evidence to support the use of our teaching

methodology, which may help to create a gold standard approach for urology

training programs throughout the country.

REFERENCES

- Vickers AJ, Bianco FJ, Serio AM, Eastham JA, Schrag D, Klein EA, et al: The surgical learning curve for prostate cancer control after radical prostatectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007; 99: 1171-7.

- Srougi M, Nesrallah LJ, Kauffmann JR, Nesrallah A, Leite KR: Urinary continence and pathological outcome after bladder neck preservation during radical retropubic prostatectomy: a randomized prospective trial. J Urol. 2001; 165: 815-8.

- Srougi M, Paranhos M, Leite KM, Dall’Oglio M, Nesrallah L: The influence of bladder neck mucosal eversion and early urinary extravasation on patient outcome after radical retropubic prostatectomy: a prospective controlled trial. BJU Int. 2005; 95: 757-60.

The Authors