RISK

OF CATECHOLAMINE CRISIS IN PATIENTS UNDERGOING RESECTION OF UNSUSPECTED

PHEOCHROMOCYTOMA

(

Download pdf )

Clinical Urology

Vol. 37 (1):

35-41, January - February, 2011

doi: 10.1590/S1677-55382011000100005

GINA SONG, BONNIE N. JOE, BENJAMIN M. YEH, MAXWELL V. MENG, ANTONIO C. WESTPHALEN, FERGUS V. COAKLEY

Departments of Radiology (GS, BNJ, BMY, ACW, FVC) and Urology (MVM), University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA

ABSTRACT

Purpose:

To report the risk of catecholamine crisis in patients undergoing resection

of unsuspected pheochromocytoma.

Materials and Methods: Over a four-year

period, we retrospectively identified four patients who underwent resection

of adrenal pheochromocytoma in whom the diagnosis was unsuspected based

on preoperative clinical, biochemical, and imaging evaluation.

Results: None of the patients exhibited

preoperative clinical features of catecholamine excess. Preoperative biochemical

screening in two patients was normal. CT scan performed in all patients

demonstrated a nonspecific enhancing adrenal mass. During surgical resection

of the adrenal mass, hemodynamic instability was observed in two of four

patients, and one of these two patients also suffered a myocardial infarct.

Conclusion: Both surgeons and radiologists

should maintain a high index of suspicion for pheochromocytoma, as the

tumor can be asymptomatic, biochemically negative, and have nonspecific

imaging features. Resection of such unsuspected pheochromocytomas carries

a substantial risk of intraoperative hemodynamic instability.

Key

words: adrenal gland neoplasms; imaging; surgery; pheochromocytoma;

catecholamines

Int Braz J Urol. 2011; 37: 35-41

INTRODUCTION

While there is widespread awareness of the classical clinical and radiological features of pheochromocytoma, it is perhaps less well known that 10% of pheochromocytomas are not associated with symptoms of excess catecholamine production, and up to 35% of pheochromocytomas have atypical imaging findings (1-5). Accordingly, the diagnosis may be unsuspected, and an indeterminate adrenal or retroperitoneal mass that is actually a pheochromocytoma could undergo resection without preoperative commencement of biochemical blockade. Such a patient is then at risk for a potentially a life-threatening intraoperative catecholamine crisis. However, while the risks of iodinated contrast administration and percutaneous biopsy have been reported in these unsuspected pheochromocytomas (6-8), to our knowledge, the risk of surgery in this population has not been well described. We recently encountered several patients who underwent surgical resection of unsuspected pheochromocytomas. Therefore, we undertook this study to report the risk of catecholamine crisis in patients undergoing resection of unsuspected pheochromocytoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective study approved by our Committee on Human Research with waiver of the requirement for informed consent. Four cases of pathologically proven pheochromocytoma that underwent attempted surgical resection were identified by the study authors between 2004 and 2007. All available imaging studies and medical records of these patients were reviewed by the principal investigator. Preoperative imaging consisted of CT scan examination obtained with multiple contiguous axial images performed in the venous phase following intravenous contrast agent in all four patients with additional delayed phases obtained in two patients. One of the patients also underwent whole body PET scan after the administration of 16.4 milliCurie intravenous fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) and utilizing attenuation-corrected regional emission images. None of the patients underwent imaging with iodine-131-meta-iodobenzylguanidine. The diagnosis of pheochromocytoma was confirmed by pathology of the surgically resected specimen in all four patients.

RESULTS

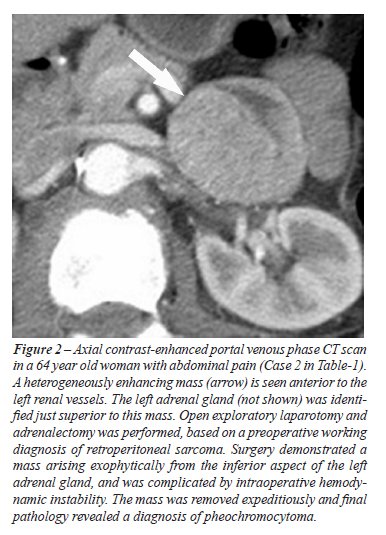

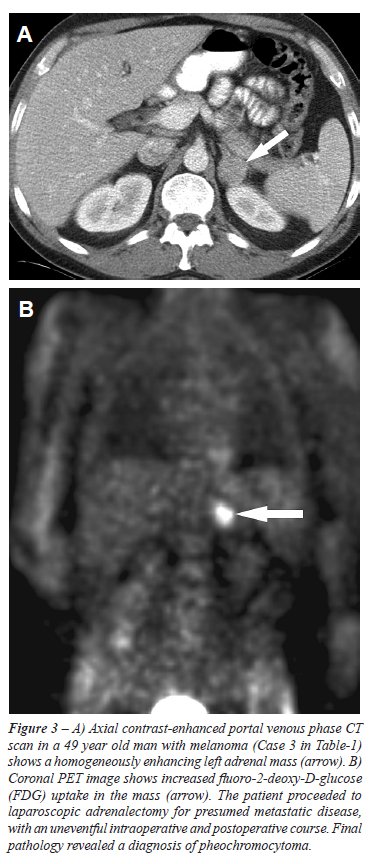

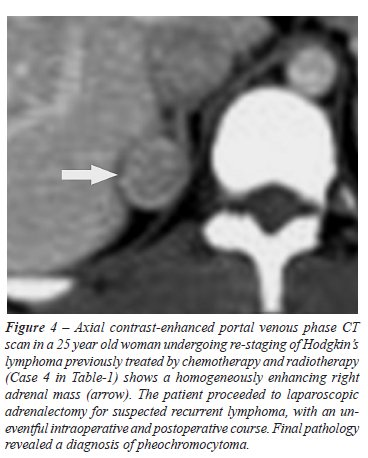

The

clinical and radiologic characteristics and intraoperative and postoperative

course of the four patients in this study are summarized in Table-1. Three

of the patients underwent imaging for purposes of staging a malignancy,

and one patient underwent imaging for abdominal pain. None of the four

patients exhibited preoperative clinical features of catecholamine excess.

One patient underwent serologic analysis, which demonstrated normal levels

of plasma metanephrine and normetanephrine. Another patient underwent

urinary analysis, which demonstrated normal levels of urinary vanillyl-mandelic

acid and normetanephrine. All patients demonstrated an adrenal mass (mean

diameter 2.7 cm, range 1.7 to 4.5 cm) with associated heterogeneous (n

= 2) or homogeneous (n = 2) enhancement on CT scan. Delayed images obtained

in two cases demonstrated less than fifty percent washout. One patient

had additional imaging with PET, which demonstrated increased FDG uptake

within the lesion. The radiological findings of the four patients are

highlighted in Figures-1 to 4. All 4 patients proceeded to adrenalectomy,

either open (n = 2) or laparoscopic (n = 2). The intraoperative course

of two patients was notable for blood pressure lability peaking at 200/100

to 220/110 mmHg systolic/diastolic. The postoperative course of one of

these two patients was complicated by an elevated troponin level to 9.7

and an electrocardiogram consistent with a non Q-wave myocardial infarction.

COMMENTS

Our

study illustrates the importance of keeping a high index of suspicion

for the possibility of pheochromocytoma for any retroperitoneal mass.

While hemodynamic instability associated with surgical and laparoscopic

resection of known or suspected pheochromocytoma has been reported (9,10),

the risk of resection in the population of unsuspected pheochromocytoma

has not been well described to our knowledge. Two out of four of our patients

demonstrated intraoperative hemodynamic instability that may have been

prevented by appropriate preoperative alpha-blockade. The postoperative

morbidity in our population might also have been averted, as the myocardial

infarction of one of our patients was presumably related to the sudden

intraoperative hypertensive challenge.

Defining typical characteristics of a pheochromocytoma

by CT is difficult as heterogeneous enhancement and poor washout as well

as FDG uptake on PET may also be seen in a metastasis or adenoma (1,4,11).

Further imaging by magnetic resonance (MR) is also problematic, as up

to 35% of pheochromocytomas do not exhibit the “lightbulb bright”

high T2 signal classically associated with pheochromocytomas (1). Current

guidelines on preoperative diagnosis thus include additional studies after

diagnosis of an adrenal mass with nonspecific characteristics on cross-sectional

imaging. Metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) reportedly has an excellent specificity

of up to 100% and may increase the sensitivity of pheochromocytoma detection

to around 80% (10,12). Given the suboptimal sensitivity of biochemical

markers alone, a combination of MIBG imaging supplemented with biochemical

testing is currently recommended (12,13). Such an imaging approach may

result in better preoperative identification of pheochromocytomas, and

facilitate commencement of pre-operative alpha blockade. Both appropriate

pretreatment with alpha blockade and readily available intraoperative

antihypertensive agents have been shown to decrease intraoperative lability

(14). While pretreatment does not exclude the possibility of intraoperative

fluctuations in blood pressure (9,10), more favorable blood pressure control

may be achieved with a combination of pretreatment and intraoperative

medications (15). In a recent series of 24 patients who underwent laparoscopic

adrenalectomy for adrenal pheochromocytoma (most were treated pre-operatively

with prazosin), no cases of intra-operative hemodynamic instability were

reported (16). While such pharmacological blockade may prevent clinically

significant hemodynamic changes, it may not prevent biochemical changes.

For example, analysis of serial catecholamine levels in 11 patients undergoing

12 laparoscopic adrenalectomies while being maintained on an intravenous

alpha 1 blocker showed significant elevations related to the induction

of pneumoperitoneum and manipulation of the adrenal gland (17).

Our report has several limitations. The

study is a small retrospective case series, and cases were not identified

systematically. Patients with enhancing adrenal masses with poor washout

or increased FDG uptake at PET imaging undergoing resection were not studied

prospectively, and as such, the frequency of pheochromocytoma in adrenal

masses with nonspecific imaging characteristics is unknown. Only two out

of four patients received screening for catecholamines, and systematic

evaluation of the rate of false negatives either by urinary or plasma

analysis was therefore not made. Further imaging with MIBG was not obtained

in any of our patients, and the rate of false negatives by MIBG was thus

not obtained.

In conclusion, we report that two of four

patients who underwent resection of unsuspected pheochromocytoma sustained

intraoperative hemodynamic instability. This study emphasizes the asymptomatic

presentation, nonspecific imaging characteristics, potential for false

negative preoperative laboratory analysis, and resultant risk of catecholamine

crisis in patients with adrenal masses. Accordingly, both surgeons and

radiologists should maintain a high index of suspicion for pheochromocytoma

before resection of nonspecific adrenal masses even in asymptomatic patients.

Further studies to better delineate the imaging and biochemical preoperative

evaluation of these patients are required.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Blake MA, Kalra MK, Maher MM, Sahani DV, Sweeney AT, Mueller PR, et al.: Pheochromocytoma: an imaging chameleon. Radiographics. 2004; 24 (Suppl 1): S87-99.

- Mayo-Smith WW, Boland GW, Noto RB, Lee MJ: State-of-the-art adrenal imaging. Radiographics. 2001; 21: 995-1012.

- Sutton MG, Sheps SG, Lie JT: Prevalence of clinically unsuspected pheochromocytoma. Review of a 50-year autopsy series. Mayo Clin Proc. 1981; 56: 354-60.

- Dunnick NR, Korobkin M: Imaging of adrenal incidentalomas: current status. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002; 179: 559-68.

- Mansmann G, Lau J, Balk E, Rothberg M, Miyachi Y, Bornstein SR: The clinically inapparent adrenal mass: update in diagnosis and management. Endocr Rev. 2004; 25: 309-40.

- Mukherjee JJ, Peppercorn PD, Reznek RH, Patel V, Kaltsas G, Besser M, et al.: Pheochromocytoma: effect of nonionic contrast medium in CT on circulating catecholamine levels. Radiology. 1997; 202: 227-31.

- Bessell-Browne R, O’Malley ME: CT of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: risk of adverse events with i.v. administration of nonionic contrast material. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007; 188: 970-4.

- Casola G, Nicolet V, vanSonnenberg E, Withers C, Bretagnolle M, Saba RM, et al.: Unsuspected pheochromocytoma: risk of blood-pressure alterations during percutaneous adrenal biopsy. Radiology. 1986; 159: 733-5.

- Kinney MA, Warner ME, vanHeerden JA, Horlocker TT, Young WF Jr, Schroeder DR, et al.: Perianesthetic risks and outcomes of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma resection. Anesth Analg. 2000; 91: 1118-23.

- Bravo EL, Tagle R: Pheochromocytoma: state-of-the-art and future prospects. Endocr Rev. 2003; 24: 539-53.

- Yoon JK, Remer EM, Herts BR: Incidental pheochromocytoma mimicking adrenal adenoma because of rapid contrast enhancement loss. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006; 187: 1309-11.

- Guller U, Turek J, Eubanks S, Delong ER, Oertli D, Feldman JM: Detecting pheochromocytoma: defining the most sensitive test. Ann Surg. 2006; 243: 102-7.

- Kudva YC, Sawka AM, Young WF Jr: Clinical review 164: The laboratory diagnosis of adrenal pheochromocytoma: the Mayo Clinic experience. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003; 88: 4533-9.

- Weismann D, Fassnacht M, Schubert B, Bonfig R, Tschammler A, Timm S, et al.: A dangerous liaison--pheochromocytoma in patients with malignant disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006; 13: 1696-701.

- Chung PC, Ng YT, Hsieh JR, Yang MW, Li AH: Labetalol pretreatment reduces blood pressure instability during surgical resection of pheochromocytoma. J Formos Med Assoc. 2006; 105: 189-93.

- Castilho LN, Simoes FA, Santos AM, Rodrigues TM, dos Santos Junior CA: Pheochromocytoma: a long-term follow-up of 24 patients undergoing laparoscopic adrenalectomy. Int Braz J Urol. 2009; 35: 24-31; discussion 32-5.

- Rocha MF, Tauzin-Fin P, Vasconcelos PL, Ballanger P: Assessment of serum catecholamine concentrations in patients with pheochromocytoma undergoing videolaparoscopic adrenalectomy. Int Braz J Urol. 2005; 31: 299-307; discussion 307-8.

____________________

Accepted after revision:

August 3, 2010

_______________________

Correspondence address:

Dr. Fergus Coakley

Chief, Abdominal Imaging

University of California San Francisco

Box 0628, M-372, 505 Parnassus Avenue

San Francisco, CA 94143-0628, USA

E-mail: fergus.coakley@radiology.ucsf.edu

EDITORIAL COMMENT

The

authors of this paper deserve to be complimented because, despite the

modest data, that was analyzed retrospectively, they raise some issues

that are very relevant for those who study and treat adrenal diseases.

First of all, they point out that adrenal

masses, and I would add retroperitoneal masses in general, can be pheochromocytomas

or paragangliomas without clinical signs or with very subtle symptoms,

which do not lead the physician to consider lesions that produce adrenergic

substances. In my personal experience (1-3), I had the opportunity to

find some pheochromocytomas that had not been diagnosed preoperatively,

much like the authors of this paper. Even worse, I found pheochromocytomas

that had been diagnosed by endocrinologists as non-functioning, which

produced adrenergic discharges in the operating room, causing all of the

risks described by the authors.

Secondly, the authors show that any surgeon is likely to encounter a patient

that has not been properly diagnosed and reacts to what he believes to

be a pheochromocytoma in the beginning of the procedure, causing hemodynamic

instability. This creates a dilemma to the surgical team: move forward

or abort the procedure? In my personal opinion, the safest measure is

to stop the procedure and adequately prepare the patient for another surgery

30 or 45 days later. However, I acknowledge that if the team is very experienced

(both surgeons and anesthesiologists), in a hospital with all the necessary

resources (medications and support), the procedure can be carried out

with good chances of success.

Finally, and this is the main point of my

analysis before the facts that were presented by the authors, each case

of adrenal mass or retroperitoneal mass suspected of being a pheochromocytoma

or a paraganglioma, regardless of the existence of symptoms, must be exhaustively

analyzed by an endocrinologist with expertise in adrenal diseases. Personally,

I do not consider myself capable of making such evaluation and I believe

that most adrenal surgeons are not. From my own personal experience, I

believe that most endocrinologists are not capable of performing this

task.

REFERENCES

- Castilho LN: Laparoscopic adrenalectomy--experience of 10 years. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2004; 48: 776-83.

- Castilho LN, Simoes FA, Santos AM, Rodrigues TM, dos Santos Junior CA: Pheochromocytoma: a long-term follow-up of 24 patients undergoing laparoscopic adrenalectomy. Int Braz J Urol. 2009; 35: 24-31; discussion 32-5.

- Castilho LN, Castillo OA, Dénes FT, Mitre AI, Arap S: Laparoscopic adrenal surgery in children. J Urol. 2002; 168: 221-4.

Dr.

Lísias Nogueira Castilho

Section of Urology

Catholic University Campinas

Campinas, SP, Brazil

E-mail: lisias@dglnet.com.br