RADICAL

CYSTECTOMY WITH PRESERVATION OF SEXUAL FUNCTION AND URINARY CONTINENCE:

DESCRIPTION OF A NEW TECHNIQUE

(

Download pdf )

MIGUEL SROUGI, MARCOS DALL’OGLIO, LUCIANO J. NESRALLAH, HOMERO O. ARRUDA, VALDEMAR ORTIZ

Division of Urology, Paulista School of Medicine, Federal University of São Paulo, UNIFESP, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Objective:

To describe the original cystoprostatectomy technique which allows the

preservation of sexual and urinary function in the majority of treated

patients.

Surgical Technique: The described technique

presents some details that distinguish it from classic cystectomy: 1)

a more efficient control of prostate venous and arterial tributaries;

2) preservation of prostatic capsule and enucleation of prostatic parenchyma,

which is removed in block together with the bladder, without violating

the vesical neck; 3) no manipulation of the distal urethral sphincteric

complex; 4) preservation of seminal vesicles and maintenance of cavernous

neurovascular bundles; 5) wide anastomosis between the ileal neobladder

and the prostatic capsule.

Comments: The proposed maneuvers allow the

performance of radical cystectomy with integral preservation of distal

urethral sphincter and of cavernous neurovascular bundles, without jeopardizing

the oncological principles.

Key

words: bladder; bladder neoplasms; cystectomy; urinary diversion;

urinary reservoirs, continence

Int Braz J Urol. 2003; 29: 336-44

INTRODUCTION

Patients

who have an invasive bladder cancer, stages T2-T4,

are currently treated with radical surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy

or with a combination of these approaches (1). According to available

data, radical cystectomy with urinary reconstruction represents the most

effective way for treating such cases, accompanied by cure rates that

oscillate between 53% to 80%, when there is no regional or systemic extension

of the disease (1).

Despite its therapeutic advantages, radical

cystectomy represents a major intervention, accompanied by morbidity rates

that should not be disregarded. In addition to the inherent post-operative

complications, radical cystectomy presented, in the past, 2 serious drawbacks.

Until the final 80s, most of these patients underwent an incontinent cutaneous

urinary diversion, which constrained them to bear urine-collecting bags,

with all the resultant psychological and social drawbacks. Furthermore,

almost all male patients developed erectile dysfunction, which compromised

their quality of life.

Upon the introduction of orthotopic intestinal

neobladders in the urologic practice (2) and the description of the technique

that allowed the preservation of cavernous neurovascular bundles (3),

the drawbacks of cutaneous ostomies and sexual dysfunction were both mitigated,

but they could not be totally avoided. About 10% of patients treated in

this way maintain severe diurnal incontinence and almost half of cases

remain with nocturnal enuresis for extended periods (4). On the other

hand, even when employing the technique for preserving the cavernous bundles,

only 50% of the treated patients evidence penile erections post-operatively

(5).

With the purpose of solving these problems,

Spitz et al. described in 1999 an alternative technique of radical cystectomy

that preserved sexual, ejaculatory, and urinary functions in treated patients

(6). Other studies were subsequently published with the same scope (7,8,9)

and all of them contemplated, in a common way, maneuvers intended to maintain

the integrity of the distal urethral sphincteric complex, responsible

for urinary continence, and the cavernous neurovascular bundles, implied

in the sexual function. Despite the significant reduction in risks of

urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction, these techniques presented

2 shortcomings witnessed by us in a small number of treated cases. The

block transection of the prostate gland along with the vesical neck is

accompanied by a more marked bleeding that the one observed when employing

classical techniques of radical cystectomy. For the same reason, preservation

of the prostatic parenchyma, common to all such new proposed techniques

creates the risk of incomplete removal of vesical neoplasia, when it infiltrates

and outgrows the vesical neck. For these reasons, we proposed a new technique

of radical cystectomy that aims to preserve the integrity of sexual and

urinary functions and that allows a greater control of intra-operative

bleeding and a more effective resection of tumors located close to the

vesical neck.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

With

the patient under general anesthesia, through a wide median abdominal

incision, the bladder is separated from the abdomen anterior wall, maintaining,

together with the organ, the parietal peritoneum that covers it superiorly.

A bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy is performed, removing the lymph nodes

located around the common, external and internal iliac vessels, and close

to the obturator vessels. Distal ureters in both sides are dissected and

sectioned close to the bladder.

Subsequently, the bladder is laterally released

from the pelvic wall and the vesicoprostatic segment is anteriorly dissected

up to the prostatic apex. The preprostatic fat is removed, carefully controlling

the superficial branch of the deep dorsal vein of penis at the level of

the prostatic apex. The intervention proceeds with transection of lateral

peritoneal wings, which fix the vesical dome to the pelvic wall. Inside

these sheets, we found the vas deferens, and in a more posterior location,

the superior vesical arteries, all of which are sectioned and ligated.

Upon releasing the bladder from the structures

that involve it anteriorly, superiorly and laterally, the hemostatic control

of arterial and venous vessels that involve the prostate begins. Prostatic

arteries, located in the vesico-prostatic sulcus on each side, are ligated

with 2 large and deep “figure-of-8” stitches, with vicryl

zero, applied next to the origin of such vessels in the inferior vesical

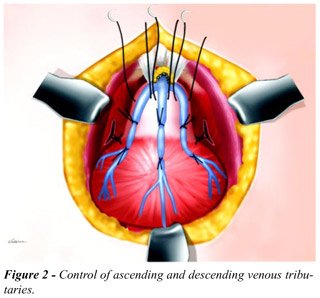

arteries (Figure-1). Next, the 3 venous trunks, one medial and two lateral,

which run over the anterior prostate surface, from the deep dorsal vein

of penis, are controlled. To accomplish this, 2 parallel and transversal

rows of 3 zero vicryl stitches are applied; with the first row located

more distally, at about 1.5 cm from the vesical neck, and other row more

proximally, at 0.5 cm from the neck (Figure-2). These stitches penetrate

deeply the prostate capsule and, once they are tied, they control the

prostate ascending venous tributaries and the bladder descending branches.

They also enable the control of arterial vessels that run in the prostatic

capsule. Before incising the prostatic capsule, a third row of 3 zero

vicryl stitches is done distally to the previous rows, and are not tied

(Figure-2). The anterior portion of the prostatic capsule is incised transversally

with an electrocautery, between the first 2 rows of stitches previously

tied, until the prostatic parenchyma is reached. Through digital and scissors-aided

dissection, the parenchyma is separated from the prostatic capsule, in

a maneuver similar to the one performed when an adenoma is enucleated.

The urethra is sectioned distally, but the base of the prostate is kept

adhered to the vesical neck, forming a single block with the bladder,

whose lumen is not violated (Figure-3). Upon the completion of the distal

enucleation of the prostate, the more distal capsular stitches are tied

and kept repaired. This maneuver allows the definitive control of tributaries

of the deep dorsal vein of the penis, which often start to bleed in the

capsulotomy’s distal margin following the prostatic enucleation.

Such intercurrence results from the loosening of the previously tied capsular

stitches, due to the enucleation of the adenoma.

At this moment, the anterior manipulation

of prostate and bladder is interrupted and the posterior dissection of

the block is proceeded. In order to create a correct plane between the

bladder and the seminal vesicles, which will be preserved, we repaired

the vas deferens in both sides at the posterosuperior surface of the bladder.

Through digital and scissors-aided dissection, the surgeon advances in

caudal direction between the bladder and the vas deferens, and then anteriorly

to the seminal vesicles, until the prostatic base is reached (Figure-4).

Resuming the anterior dissection of the specimen and maintaining a small

sponge between the bladder and the seminal vesicles, the capsulotomy is

completed in its posterior half, with a special precaution to avoid damage

to the cavernous neurovascular bundles (Figure-5). These maneuvers culminate

with the complete release of the bladder-prostatic adenoma block, which

will be removed, and the distal prostatic capsule, preserved. Samples

of tissue from the distal margin of the capsule are removed and submitted

to freezing pathologic study in order to confirm the absence of residual

neoplasia.

Cystectomy is completed sectioning the 2

lateral vesical pedicles, performed with the aid of Mixter forceps or

hemoclamps applied in craniocaudal direction. The specimen formed by the

bladder connected to prostatic adenoma is removed, the prostatic cavity

and the capsular margins are revised and small bleeding vessels are controlled

with electrocautery or with “figure-of-8” 3-zero vicryl stitches.

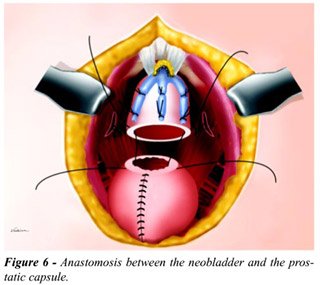

The intervention proceeds with the construction

of an orthotopic ileal neobladder, for which we use Camey II or Studer

techniques (2,10). Once the neobladder is done and double-J catheters

are inserted in both ureters, the anastomosis between the neobladder and

the remaining distal prostatic capsule is performed (Figure-6). This anastomosis

is made with a continuous 2-zero vicryl suture, and before its completion

a 20F Foley urethral catheter is placed in the neobladder, and the distal

ends of both double-J catheters are tied to it.

Surgery is finished with the installation

of continuous suction drains at the level of the anastomosis between the

neobladder and the prostate and near the sites of ureteral implantation.

These drains are maintained until the 7th post-operative day and the Foley

catheter, tied to the double-J catheters, are removed on the 20th day

after the intervention.

COMMENTS

In

this work we present an original alternative technique for radical cystectomy,

which allows integral preservation of urinary continence and reduces substantially

the risks of sexual impotence. In an initial group of 6 treated patients,

5 presented complete diurnal and nocturnal continence immediately after

removing the urethral catheter, 3 referred penile erections on the first

month and none evidenced positive surgical margins at the level of vesical

neck or prostatic parenchyma.

In contrast to the classical radical cystoprostatectomy

technique, this method preserves the prostatic capsule, the cavernous

neurovascular bundles and is not accompanied by manipulation of the distal

urethral sphincteric complex. For such reasons, this technique, which

could be referred to as cysto-adenomectomy, has a highly favorable impact

over the maintenance of urinary and sexual functions post-operatively.

Another advantage of this technique is the fact that it is accompanied

by a block removal of bladder and prostatic parenchyma, reducing the risks

of incomplete removal of the vesical neoplasia, when it invades the vesical

neck and the prostate by intraluminal direct extension.

Under a surgical perspective, this method

incorporates maneuvers that allow a quite efficient control of the anterior

periprostatic venous trunks and the lateral prostatic arteries (11), significantly

reducing intra-operative bleeding. As a matter of fact, none of the 6

patients treated up to now, required blood transfusions during or after

surgery.

The only drawback of the cysto-adenomectomy

technique, compared with the classic radical cystectomy, is that it does

not remove a prostate cancer when this tumor is coincidentally present

in addition to the vesical neoplasia (12). To minimize this problem, the

cysto-adenomectomy technique must be indicated when the existence of a

prostate cancer is highly unlikely, that is, in patients with medical

examination and normal serum levels of prostatic specific antigen or,

in case of doubt, with negative pre-operative prostatic biopsy.

The first proposal about preservation of

sexual and ejaculatory function in radical cystectomy was made in 1999

(6). These authors described a technique that removed the anterior half

of the prostate and preserved its posterior portion. After that, 3 more

studies were published with the same objective, all of them proposing

the preservation of the prostate and bladder resection with distal transection

of the specimen at the level of the vesical neck (7,8,9). Despite highly

elevated rates of maintenance of sexual and urinary function observed

with these techniques, they presented, as a common feature, the risk of

violating the bladder tumor and producing positive distal margins, when

the neoplasia reaches the vesical neck. This risk was reduced by Colombo

et al. (9) and by Vallancien et al. (8) who performed the endoscopic resection

of the vesical neck and the prostate previously, but even then, the potential

risk of violating the neoplasia persists when the vesical neck is sectioned

transversely. In our technique, this possibility is minimized due to the

block removal of prostatic parenchyma, vesical neck and bladder.

Another advantage of this cysto-adenomectomy

technique in relation to other published approaches is that it implies

in removing the specimen in one stage. Both previous endoscopic resection

(9) and that performed at the moment of cystectomy (8) increase the length

and morbidity of the intervention.

If the ongoing study by our group confirms

better preservation of urinary continence and a lower incidence of post-operative

sexual dysfunction, this technique may become a preferential method for

performing radical cystectomy in men with invasive bladder cancer. In

such cases, the method could be employed every time that the presence

of a primary prostate cancer is previously ruled out, and when there is

no extensive secondary involvement of the prostate gland from the vesical

neoplasia.

REFERENCES

- Sternberg CN: Current perspectives in muscle invasive bladder cancer. Eur J Cancer 2002, 38: 460-467.

- Barre PH, Herve JM, Botto H, Camey M: Update on Camey II procedure. World J Urol. 1996, 14: 27-28.

- Schlegel PN, Walsh PC: Neuroanatomical approach to radical cystoprostatectomy with preservation of sexual function. J Urol. 1987, 138: 1402-1406.

- Soulie M, Seguin P, Mouly P, Thoulouzan M, Pontonnier F, Plante P: Assessment of morbidity and functional results in bladder replacement with Hautmann ileal neobladder after radical cystectomy: a clinical experience with highly selected patients. Urology 2001, 58: 707-711.

- Miyao N, Adachi H, Sato Y, Horita H, Takahashi A, Masumori N, et al.: Recovery of sexual function after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy or cystectomy. Int J Urol. 2001, 8:158-164.

- Spitz A, Stein JP, Lieskovasky G, Skinner DG: Orthotopic urinary, diversion with preservation of erectile and ejaculatory function in man requiring radical cystectomy for nonurothelian malignancy: a new technique. J Urol. 1999, 161: 1761-1764.

- Horenblas S, Meinhardt W, Ijzerman W, Moonen LFM: Sexuality preserving cystectomy and neobladder: initial results. J Urol. 2001, 166: 837-840.

- Vallancien G, El Fettouh HA, Cathelineau X, Baumert H, Fromont G, Guillonneau B: Cystectomy with prostate sparing for bladder cancer in 100 patients: 10-year experience. J Urol. 2002, 168: 2413-2417.

- Colombo R, Bertim R, Salonia A, Da Pozzo LF, Montorsi F, Brausi M, et al.: Nerve and seminal sparing radical cystectomy with orthotopic urinary diversion for selected patients with superficial bladder cancer: an innovative surgical approach. J Urol. 2001, 165: 51-55.

- Modersbacher S, Hechreiter W, Burkhard F, Thalmann GN, Danuser H, Markwalder R, et al.: Radical cystectomy for bladder cancer today – a homogenous series without neoadjuvant therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2003, 21: 690-696.

- Srougi M, Dall’Oglio MF, Bomfim AC, Andreoni C, Cury J, Ortiz V: An improved technique for bleeding control during simple retropubic prostatectomy. BJU Int (in press).

- Chun TY: Coincidence of bladder and prostate cancer. J Urol. 1977, 157: 65-67.

__________________

Received:

April, 2003

Accepted: May, 2003

_______________________

Correspondence address:

Dr. Miguel Srougi

Rua Peixoto Gomide 2055/81

01409-003, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

Fax: + 55 11 3257-9006

E-mail: srougi@attglobal.net

Srougi

et al. adapted a few technical maneuvers acquired from years of performing

radical and simple prostatectomies and applied them to a cystoprostatectomy

with orthotopic neobladder. The objective is to preserve sexual function

and improve urinary continence. In my experience patients have excellent

daytime continence (< 5% wear pads) although 15% empty by intermittent

catheterization. Nighttime incontinence is infrequent since most of my

patients wake up at least once per night. I have elected to taper the

ileum at the site of the urethral anastomosis which may add to the functional

urethral length. I am not certain how important this is.

The

issue of preserving erectile function is an important one for a relatively

small subset of men who have a cystoprostatectomy and neobladder. The

percentage of men who are candidates for this prostate capsule sparing

is relatively low among all of the men I evaluate for surgery. The majority

of men is older or has advanced local disease and thus they are impotent

or the extent of disease makes invasion of the prostate a concern. I believe

the patient must be one who understands the need for subsequent careful

monitoring - not only for urothelial cancer but for adenocarcinoma of

the prostate.

The

men who are most likely to benefit from these modifications of the standard

cystoprostatectomy are younger men who have recurrent or persistent high

grade Ta, CIS, or T1 bladder cancer and have failed intravesical therapy.

Once tumor at the bladder neck (?) and prostatic urethra is excluded they

might be reasonable candidates for this approach.

There

are some trade-offs when comparing the standard procedure in which the

entire prostate and seminal vesicles are removed with Srougi’s modification

which leaves the prostate capsule and seminal vesicles. This is not much

different however, from leaving the neurovascular bundles, bladder neck,

and the distal seminal vesicles during a radical prostatectomy with the

desire to improve the chance of retaining normal pre-op erectile function.

Each case must be carefully judged based on pre and intraoperative findings

as well as a variety of patient issues such as age and erectile function

before surgery.

______________

Mark S. Soloway

Chairman, Department of Urology

University of Miami School of Medicine

Miami, Florida, USA

EDITORIAL COMMENT

En

bloc removal of the bladder, prostate, ampullae of the vasa deferentia

and seminal vesicles is now the paradigm treatment for muscle invasive

and recurrent high grade urothelial carcinomas. However, largely due to

significant associated morbidities and only modest cure rates when applied

as a monotherapy, initial acceptance of this procedure was not broad.

Over the past 30-years both medical and urologic oncologists have made

dramatic strides to improve the adverse consequences of effectively treating

urothelial cancer. Medical oncologists have graduated patients from non-effective,

single-agent chemotherapy to the latest less-toxic but efficacious combination

of paclitaxel, carboplatin and gemcitabine. With improved survival, urologic

oncologists have modified their surgical execution to reduce morbidity

and improve the social, sexual and psychological implications of radical

cystectomy. Lower urinary tract reconstruction has evolved from simple

cutaneous ureterostomies and ileal conduits to continent cutaneous urinary

reservoirs, and most recently the continent orthotopic neobladders. Today

men and women can safely undergo orthotopic lower urinary tract reconstruction

to the intact native urethra while preserving the erectile nerve bundles

and importantly, the pelvic plexus supplying these nerve bundles. This

has given witness to a dramatic improvements in both the longevity and

quality of our patients’ lives.

For

continuing these forward strides in surgical techniques with their described

method, a modification of that previously described by the USC group (authors’

reference 6), the authors are to be commended. And we are sure that many

innovative surgeons will continue to refine this technique to provide

even better outcomes for the patient of tomorrow.

But

in this search for minimal morbidity, let’s not forget in whom and

for what reason the vast majority of radical cystectomies are performed.

Today the average male patient requiring cystectomy for bladder cancer

is in his sixth decade of life when the reproductive necessity of preserving

ejaculatory function has generally long since past. In the end, this is

the one morbidity of standard nerve sparing radical cystoprostatectomy

that we see as preserved through this technique, and this is accomplished

with a questionable overall improvement in life’s quality for the

vast majority of men with urothelial carcinoma. We are further puzzled

as to the mechanism of antegrade ejaculation following the removal of

a functional bladder neck and the necessity for its coordinated closure

to provide antegrade emission of deposited seminal fluids.

With

a very conscious recognition of the anatomic location of the pelvic plexus

lateral to the seminal vesicles and its nervous supply to the erectile

nerve bundle as depicted in authors’ Figure-1, maintaining the erectile

nerve bundles should be no more difficult during radical cystoprostatectomy

than radical prostatectomy. We commonly perform retrograde release of

the nerve bundles from apex to base during radical cystoprostatectomy

as we perform it during radical prostatectomy. Similar to the reports

of others, this approach has allowed us to preserve erectile function

at rates similar to that seen following isolated radical prostatectomy

(1). While this approach obviates ejaculatory function, is this truly

an issue for the majority of patients undergoing radical cystoprostatectomy?

We

then re-focus on the patients in whom the majority of these surgeries

are performed; sixty-year-old men, who also have the highest incidence

of prostate cancer (2). Furthermore, we now recognize that a significant

number of prostate cancers exist in men with serum PSA below 3ng/ml, the

majority of which are clinically significant (3,4). The benefits of a

radical cystectomy which preserves the posterior lateral zones of the

prostate might quickly fade for the patient and physician alike when the

serum PSA starts rising and there is limited hope of performing completion

prostatectomy and reconstruction of the orthotopic neobladder.

The

authors’ approach is certainly appealing when ejaculatory preservation

is a quality of life issue. We however caution that this select patient

is few and far between. For the young (20 to 30 year-old) male with benign

bladder disease necessitating cystectomy (refractory cystitis glandularis)

or non-urothelial carcinoma away from the bladder neck in whom fertility

is an issue, this technique, offering ejaculatory preservation, even if

ejaculation is retrograde into the neobladder where it can be harvested,

is alluring. For all others we feel there is little benefit to be gained

by this technique over a properly performed nerve sparing cystoprostatectomy

References

- Ghavamian R, Zincke H: An updated, simplified approach to nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy. BJU Int. 1999; 84:160-163.

- Sarma AV, Schottenfeld D: Prostate cancer incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States: 1981-2001. Semin Urol Oncol. 2002; 20:3-9

- Recker F, Kwiatkowski MK, Huber A, Stamm B, Lehmann K, Tscholl R: Prospective detection of clinically relevant prostate cancer in the prostate specific antigen range 1 to 3 ng./ml. combined with free-to-total ratio 20% or less: the Aarau experience. J Urol. 2001; 166: 851-5

- Ward JF, Bartsch T, Sebo TJ, Pinggera G-M, Blute ML, Zincke H: Pathologic characterization of prostate cancers with a very low serum prostate specific antigen (0-2 ng/mL) incidental to cystoprostatectomy: Is PSA a useful indicator of clinical significance? Urol Oncol (in press).

_______________

Dr. John F. Ward

Fellow in Uro-Oncologic Surgery

Department of Urology, Mayo Medical School

Rochester, Minnesota, USA

Dr. Horst

Zincke

Professor of Urology, Mayo Medical School

Consultant, Department of Urology

Rochester, Minnesota, USA

EDITORIAL COMMENT

The

concept of preservation of the prostate at the time of cystectomy for

bladder cancer is not new and has been applied sporadically since early

in the twentieth century. I first preserved the prostate capsule in 1985

using a technique somewhat similar to Srougi and subsequently in several

carefully selected patients. I have been reluctant to publish these cases

due to the uncertainty as to whether this technique will be viable in

the long term. Clearly, interest in this technique has escalated with

this recent report and the larger series of Vallancien et al. from France

(1).

While

there are some early signs that this technique may be beneficial for some

patients, the benefits versus the risks of the technique must be addressed

before its widespread use. The benefits include probable decrease in blood

loss, probable improved continence, and probable improved erectile function

recovery. I emphasize the “probable” aspect because the degree

of improvement is certainly unquantified, despite the initial observations

of Srougi and my experience as well. A validated Quality of Life instrument

suitable to quantify erectile function and incontinence after a cystectomy

and neobladder surgery is not currently available; thus the magnitude

of improvement from this technique will be debatable until studied in

an appropriate fashion.

The

risks are also unquantified. Using whole-mount step-sectioning of the

prostate, it has been determined that approximately 40% of bladder cancer

cystectomy patients may harbor unsuspected urothelial carcinoma in situ

in the prostatic urethra or prostatic ducts (2,3). Similarly, 40% to 50%

of patients have unsuspected adenocarcinoma of the prostate (most of which

are small and of uncertain clinical significance) (3). Since the patient

populations with urothelial and adenocarcinomas do not necessarily overlap,

40% to 80% of patients might have a neoplasm in the prostate which may

make it unwise to leave the prostate capsule behind. Much of this risk

may be obviated by careful patient selection and presurgical screening

for prostate cancers as suggested by Srougi, and a frozen section of the

adenomatous tissue removed from the prostate. If the frozen section reveals

either urothelial or adenocarcinoma at the time of surgery, the prostate

capsule and seminal vesicle could be removed. If the frozen section is

benign, the neobladder could be sewn to the prostate capsule as described

in Srougi’s report.

As

with many procedures in oncology, the evolution is towards smaller, less

extensive operations that still reliably eliminate the cancer but preserve

better function (e.g., lumpectomy and radiation for breast cancer or nerve-sparing

radical prostatectomy). Maybe it is time for a more critical study of

a tailored radical cystectomy for urothelial cancer. Careful patient selection

will unquestionably be the most important aspect.

References

- Vallancien G, Abou El Fettough H, Cathelineau X, Baumert H, Fromont G, Guillonneau B: Cystectomy with prostate sparing for bladder cancer in 100 patients: 10-year experience. J Urol. 2002; 168: 2413-7.

- Wood DP, Montie JE, Pontes JE, VanderBrug Medendorp S, Levin HS: Transitional cell carcinoma of the prostate in cystoprostatectomy specimens removed for bladder cancer. J Urol. 1989; 141: 346-9.

- Mahadevia PS, Koss LG, Tar IJ: Prostatic involvement in bladder cancer: Prostate mapping in 20 cystoprostatectomy speciems. Cancer 1986; 58: 2096-102.

_________________

Dr. James E. Montie

Chairman, Dept Urology, Univ of Michigan

Valassis Professor of Urologic Oncology

Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA