INFANTILE

BLADDER RUPTURE DURING VOIDING CYSTOURETHROGRAPHY

(

Download pdf )

ABDOL M. KAJBAFZADEH, PARISA SAEEDI, ALI R. SINA, SEYEDMEHDI PAYABVASH, AMIRALI H. SALMASI

Pediatric Urology Research Center, Department of Urology, Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

ABSTRACT

Bladder rupture is rare during infancy and most of reported cases had urethral obstruction or neurogenic bladder. We report two cases of infantile bladder rupture during voiding cystourethrography (VCUG). This report reinforces the criteria for proper VCUG imaging procedure. Consideration of expected bladder volume for body weight, and close monitoring of bladder pressure and injection speed could prevent such complications.

Key

words: bladder; children; diagnostic imaging; rupture; iatrogenic

Int Braz J Urol. 2007; 33: 532-5

INTRODUCTION

Voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) is widely applied for the radiological evaluation of the bladder and urethra in children. Bladder rupture during VCUG is exceedingly rare (1). We present two infants with iatrogenic bladder rupture during VCUG performed by radiology staffs in two district hospitals. These infants were referred to our center for further management.

CASE REPORTS

Case

#1 - A 10-day-old boy, weighing 3.2 kg, was referred to nephrologists

with history of prenatal hydronephrosis. On day 7 after birth, ultrasonographic

exam confirmed bilateral hydroureteronephrosis, which was severe on the

left side and mild on the right side. VCUG was requested to evaluate a

possible vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). A 6F feeding tube was inserted into

the urethra and contrast media was injected using a 50-mL syringe, under

fluoroscopic guide. During the first filling cycle, severe left side VUR

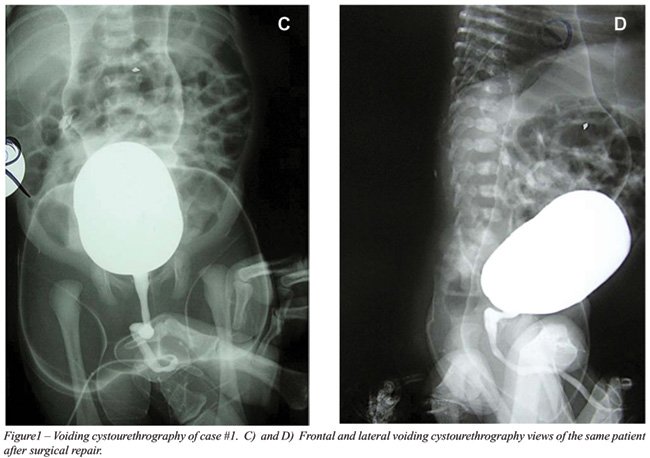

appeared following injection of 15 mL of contrast media (Figure-1) and

the right VUR appeared in volume of 35 mL. However, the radiographer continued

the instillation until the intraperitoneal bladder rupture occurred in

volume of 60 mL (Figure-1). The baby was referred to urologist and immediately

underwent abdominal exploration through a Pfannenstiel incision. The bladder

dome was the site of a 2 cm long rupture. The peritoneal cavity was washed

with saline and the bladder was closed in two layers using 4-0 polyglactin

suture. A Malecot catheter was inserted in the bladder as suprapubic tube.

A mini-vacuum closed drain was left in the perivesical space. The post-operative

course was complicated by prolonged urine leakage from the site of suprapubic

catheter extracted on the 14th postoperative day. The child

was referred to our institution for further management. A 6F Foley urethral

catheter was inserted. After 7 days, the leakage was stopped and the catheter

was removed on the 24th postoperative day. The patient was

discharged 3 days later with good condition and prescription of prophylactic

antibiotic (Figure-1).

Case #2 - A 9-month old female infant, weighing

7 kg, was referred to a radiologist for VCUG at a district hospital from

a different province. Medical problems included urinary tract infection

and failure to thrive. Contrast media was injected through an 8F urethral

feeding tube under fluoroscopic guide. The radiographer instilled 100

mL of contrast media using a 50-mL syringe, during the first filling cycle.

Speed of injection, bladder pressure and volume were not recorded. While

reviewing the images, the radiologist discovered bladder perforation.

She was taken to the operating room and underwent abdominal exploration.

The bladder was exploded at dome with a 3 cm length. The site of perforation

was closed in two layers using absorbable 4-0 polygalactin suture. A small

Penrose drain was left in perivesical space and a 10F catheter was left

per urethra. Post-operative course of the patient was uneventful and she

was discharged one week later and referred to our clinic for further evaluation.

Follow-up VCUG showed no leakage or reflux.

COMMENTS

Infantile

bladder rupture is rare (2) and only 17 cases have been reported between

1956 and 1985 (3). The main predisposing factors include posterior urethral

valves and neurogenic bladder followed by bladder outlet obstruction from

other etiologies and trauma (3). Few cases of iatrogenic bladder perforation

have been reported in children following diagnostic and therapeutic procedures

(3,4). To our knowledge this is the second report of infantile bladder

rupture during VCUG (2).

There was none of the above-mentioned risk

factors in our cases; however, inaccurate imaging procedure seems to be

the main cause of perforation. In order to perform a safe and perfect

VCUG, radiologists must pay attention to some factors such as bladder

volume, style of contrast media instillation and patient conditions (underlying

urinary disease) (1). Two formulae have been proposed for bladder volume

estimation in children with regards to their weight and age (4,5); age

< 2 years - bladder volume (mL) = weight (kg) × 7, age > 2

years - bladder volume (mL) = [age (years) + 2] × 30.

Proper catheter insertion, fluoroscopic

guide, pressure and number of filling cycle should be considered in styles

of instillation (1). To avoid pressure overload, hand injection of contrast

material must not be used and the contrast container should not be placed

higher than 60 cm from the patient. More than two cycles of filling does

not appear to be necessary (1,6). The underlying urinary system disease

is another important factor. In our cases, the bladder volume and pressure

were not considered and the contrast media was instilled directly by syringe.

Management of infantile bladder rupture

should be individualized. In the review by Trulock et al. (3), the majority

of reported neonates were treated with abdominal exploration and repair

of the bladder leakage site; however some of the patients would be managed

by the use of vesicostomy or urethral catheter alone.

In conclusion, during VCUG, it is important

to consider the patient underlying disorder and expected bladder volume

for age as well as to avoid hand injection of contrast material and placing

the contrast container more than 60 cm higher than the patient. Moreover,

in order to prevent high-pressure voiding in premature infants, it has

been recommended to use small caliber and balloon-less feeding catheters

that would not occlude the bladder neck during voiding.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Agrawalla S, Pearce R, Goodman TR: How to perform the perfect voiding cystourethrogram. Pediatr Radiol. 2004; 34: 114-9.

- Wosnitzer M, Shusterman D, Barone JG: Bladder rupture in premature infant during voiding cystourethrography. Urology. 2005; 66: 432.

- Trulock TS, Finnerty DP, Woodard JR: Neonatal bladder rupture: case report and review of literature. J Urol. 1985; 133: 271-3.

- O’Brien WJ, Ryckman FC: Catheter-induced urinary bladder rupture presenting with pneumoperitoneum. J Pediatr Surg. 1994; 29: 1397-8.

- Koff SA: Estimating bladder capacity in children. Urology. 1983; 21: 248-52.

- Jequier S, Jequier JC: Reliability of voiding cystourethrography to detect reflux. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989; 153: 807-10.

____________________

Accepted after revision:

April 27, 2007

_______________________

Correspondence

address:

Dr. A.M. Kajbafzadeh

No. 36, 2nd Floor, 7th Street

Saadat-Abad, Ave. Tehran 19987, Iran

Fax: + 98 21 2206-9451

E-mail: kajbafzd@sina.tums.ac.ir

EDITORIAL COMMENT

The authors of this manuscript present two cases of iatrogenic bladder rupture in infants undergoing voiding cystourethrograms. This radiographic study is one of the most common imaging studies ordered in children and needs to be performed safely and reliably. Those of us who work in dedicated children’s hospitals take this for granted. However, the cases reported in this series were performed by radiologists clearly unfamiliar with proper technique as nicely outlined by the authors. It is important to remember that the peritoneum drapes quite anteriorly in small children thus making a rupture very likely to be intraperitoneal, as in these two cases, and therefore surgical exploration is required.

Dr. Lane

S. Palmer

Chief, Pediatric Urology

Schneider Children’s Hospital

North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System

New York, NY, USA

E-mail: lpalmer@nshs.edu