RE:

INFLAMMATORY ATROPHY ON PROSTATE NEEDLE BIOPSIES: IS THERE TOPOGRAPHIC

RELATIONSHIP TO CANCER?

(

Download pdf )

ATHANASE BILLIS, LEANDRO L.L.FREITAS, LUIS A. MAGNA, UBIRAJARA FERREIRA

Departments of Anatomic Pathology (AB,LLLF), Genetics and Biostatistics (LAM), and Urology (UF), School of Medicine, State University of Campinas (Unicamp), Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil

Int Braz J Urol 2007;33:355-63

To the Editor:

The

editorial comments of our paper by Dr.H.Samaratunga, Dr. Rodolfo Montironi,

and Dr. Liang Cheng were very informative on a lesion that is one of the

most frequent mimics of prostatic adenocarcinoma. It occurs most frequently

in the posterior lobe or peripheral zone (1-3) and gained importance with

the increasing use of needle biopsies for the detection of prostatic carcinoma

(4). Moore (1), in 1936, was one of the first authors to describe prostatic

atrophy in a systematic autopsy study. He found that there was a strong

correlation with age and, according to his study, prostatic atrophy is

initiated during the 5th decade and continues as a progressive process

into the 8th decade. It is a frequent lesion: 85% in autopsies and 83.7%

in needle biopsies (5,6).

Why this lesion mimics adenocarcinoma? Histologically

prostatic atrophy may be partial or complete. The latter is subtyped in

simple, hyperplastic (or post-atrophic hyperplasia), and sclerotic (5).

It seems that the subtypes represent a morphologic continuum of a single

lesion (4). Partial atrophy and hyperplastic (or postatrophic hyperplasia)

most frequently mimic adenocarcinoma. Hyperplastic atrophy shows small

acini closely packed together and lined by atrophic epithelium. Fibrosis

is present or not in the stroma. When present, the proliferation is irregular

and can result in distortion of the acini simulating stromal infiltration

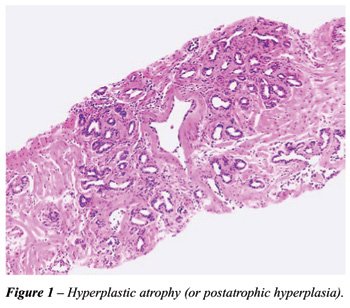

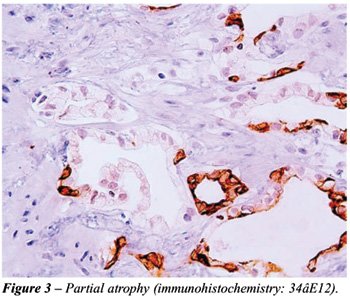

(Figure-1). Partial atrophy was described by Oppenheimer et al. (7). The

name is due to the fact that there is partial preservation of the cytoplasm

simulating neoplastic micro-acini (Figure-2). An additional pitfall for

the surgical pathologist is the fact that in partial atrophy the basal

cells may be scattered and in some acini may be completely absent (Figure-3).

There are some findings associated to the

etiopathogenesis of the lesion. Atrophy is clearly associated to advanced

age (1,5). Radiotherapy and hormonal deprivation are associated with diffuse

atrophy. Inactive or active inflammation is a frequent cause for the lesion

(8) and based on a study on autopsies there is evidence that chronic local

ischemia may also be a cause of atrophy (5). However, many examples of

atrophy are still considered idiopathic in nature. Both inflammation and

ischemia are associated with focal forms of atrophy.

The relation of prostatic atrophy to neoplasia

is exciting and controversial. This topic was thoroughly commented in

our study and discussed in the editorial comments by Dr.H.Samaratunga,

Dr. Rodolfo Montironi, and Dr. Liang Cheng (6).

In diagnostic practice it is not rare to

find patients with serum prostate- specific antigen (PSA) elevation and

several biopsies showing no atypical, preneoplastic or neoplastic lesions,

except prostatic atrophy. Regardless of the cause, we hypothesized that

damaged epithelial cells in atrophic acini could be a source of the elevation

of PSA. Our study was based on 131 needle prostatic biopsies corresponding

to 107 patients. The only diagnosis in all biopsies was focal prostatic

atrophy without the presence of cancer, high-grade prostatic intraepithelial

neoplasia, or areas suspicious for cancer. A positive and significant

association was found between the extent of atrophy and the total or free

serum PSA elevation (9). All patients showing 35mm or higher linear extent

of atrophy in the biopsy cores, had serum PSA above 4ng/mL. The findings

suggest that damaged epithelial cells in atrophic acini, regardless of

cause, could be a source of serum PSA elevation.

Prostate-specific antigen is a single chain

glycoprotein with proteolytic enzyme activity mainly directed against

the major gel-forming protein of the ejaculate (semenogelin). PSA induces

liquefaction of semen with release of progressively motile spermatozoa

(10). There are several efficient physiologic barriers to prevent the

escape of any significant amounts of PSA from the prostatic ductal system:

basement membrane of the acini, basal cells lining the acini, prostatic

stroma, basement membrane of capillary endothelial cells, and endothelial

cells. These barriers normally prevent PSA from entering the general circulation

at concentrations of more than 3ng/mL (10).

Focal prostatic atrophy represents a form

of adaptive response to injury most commonly to inflammation and/or local

ischemia. It is intriguing that atrophic acini may produce an excess of

serum PSA. Inflammation and/or ischemia are injurious stimuli resulting

in diminished oxidative phosphorilation, membrane damage, influx of intracellular

calcium, and accumulation of oxygen-derived free radicals (oxidative stress)

(11). We speculate that these injurious stimuli may interfere in the physiologic

barrier that prevent the escape of any significant amounts of PSA to the

general circulation.

Atrophy is a frequent, exciting, intriguing

lesion and a relevant subject for further research. Pathologists should

include the presence and extent of the lesion in the pathology report.

References

1. Moore RA: The evolution and involution of the prostate gland. Am J

Pathol. 1936;12:599-624.

2. Franks LM: Atrophy and hyperplasia in the prostate proper. J Pathol

Bacteriol. 1954;68:617-21.

3. Liavag I: Atrophy and regeneration in the pathogenesis of prostatic

carcinoma. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand [A]. 1968;73:338-50.

4. Cheville JC, Bostwick DG: Postatrophic hyperplasia of the prostate.

A histologic mimic of prostatic adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1068-76.

5. Billis A: Prostatic atrophy: An autopsy study of a histologic mimic

of adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:47-54.

6. Billis A, Leandro LL Freitas, Luis A Magna, Ubirajara Ferreira: Inflammatory

atrophy on prostate needle biopsies: Is there topographic relationship

to cancer? Int Braz J Urol. 2007;33:355-63.

7. Oppenheimer JR, Wills ML, Epstein JI: Partial atrophy in prostate needle

cores: another diagnostic pitfall for the surgical pathologist. Am J Surg

Pathol. 1998;22:440-5.

8. Srigley JR: Benign mimickers of prostate cancer. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:328-48.

9. Billis A, Meirelles LR, Magna LA, Baracat J, Prando A, Ferreira U.

Extent of prostatic atrophy in needle biopsies and serum PSA levels: is

there an association? Urology. 2007;69:927-30.

10. Oesterling JE, Lilja H: Prostate-specific antigen. The value of molecular

forms and age-specific reference ranges. In: Vogelzang NJ, Scardino PT,

Shipley WU, Coffey DS (eds.), Comprehensive textbook of genitourinary

oncology. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins. 1996; pp.668-80.

11. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of

Disease, 7th ed. Philadelphia, Elsevier Sanders.2005; pp.3-46.

Dr. Athanase Billis

Full-Professor of Pathology

State University of Campinas, Unicamp

Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil

E-mail: athanase@fcm.unicamp.br