IS

CONTINENT URINARY DIVERSION FEASIBLE IN CHILDREN UNDER FIVE YEARS OF AGE?

(

Download pdf )

LUIZ L. BARBOSA, RIBERTO LIGUORI, SERGIO L. OTTONI, UBIRAJARA BARROSO JR, VALDEMAR ORTIZ, ANTONIO MACEDO JUNIOR

Division of Urology, Federal University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Purpose:

To review our clinical experience with urinary continent catheterizable

reservoir in children under five years of age.

Materials and Methods: A total of 23 patients

(16 males, 7 females) with a median age of 3.64 years were evaluated.

Among these, 6 (26.08%) had a posterior urethral valve, 9 (39.13%) myelomeningocele,

4 (17.39%) bladder exstrophy, 2 (8.69%) genitourinary rabdomyosarcoma,

1 (4.34%) had spinal tumor and 1 (4.34%) an ano-rectal anomaly.

Results: Perioperative complications were

observed in four patients consisting of one febrile urinary tract infection,

one partial operative wound dehiscence, one partial stomal dehiscence

and one vesico-cutaneous fistula after a secondary exstrophy repair. The

overall long-term complications rate was 40.90% and consisted of two stomal

stenoses (9.09%), one neobladder mucosal extrusion (4.54%), three neobladder

calculi (13.63%) and persistence of urinary incontinence in three patients

(13.63%). The overall surgical revision was 36.36% and final continence

rate was 95.45% with mean follow-up of 39.95 months

Conclusion: Continent urinary diversion

is technically feasible even in small children, with acceptable rates

of complications.

Key

words: children; congenital anomalies; urinary diversion; continence

Int Braz J Urol. 2009; 35: 459-66

INTRODUCTION

The ability to void spontaneously

may be compromised in children with various congenital urologic abnormalities

(neurogenic bladder, posterior urethral valve and bladder exstrophy).

Although clean intermittent catheterization (CIC), pharmacological treatment

and overnight catheter drainage has changed the natural history of most

of these uropathies., it is not always possible to avoid renal deterioration

in these patients owing to a combination of high detrusor pressure, infection

and vesicoureteral reflux, moreover, urethral catheterization can be painful

or not possible in female patients bound to a wheel chair.

The use of continent urinary reservoirs

has gained wide acceptance, because when this procedure is combined with

CIC, patients are often able to achieve continence with low intravesical

pressure. If necessary, a continent catheterizable urinary reservoir and

a concomitant bladder neck procedure can be helpful to restore continence.

On the other hand, each type of augmentation

cystoplasty involves short-term and long-term morbidity (bacteriuria,

pyelonephritis, mucus production, stone disease, metabolic disturbances,

bladder rupture/perforation and malignancy) that may lead to impaired

linear growth in young children (1,2). To our knowledge, there is no consensus

in the literature as regards patients’ initial age when this procedure

can be safely performed. The majority of the series report bladder augmentation

in patients above 5 years of age (> 5 years).

We retrospectively present our experience

with orthotopic continent urinary diversion in children under five years

of age. We evaluated all continent catheterizable procedures that were

performed in our institution, to investigate if continent urinary diversion

is technically feasible and safe even in younger children.

MATERIALS AND

METHODS

The

records of children who underwent a Macedo’s continent catheterizable

reservoir below five years of age were retrospectively reviewed. A total

of 23 patients (16 males, 7 females) met the inclusion criteria in our

present series of 115 procedures. Patient age at surgery varied from 1

to 5 years with median age of 3.64 years. All children had previously

undergone urodynamic evaluation, except those with rabdomyosarcoma and

bladder exstrophy.

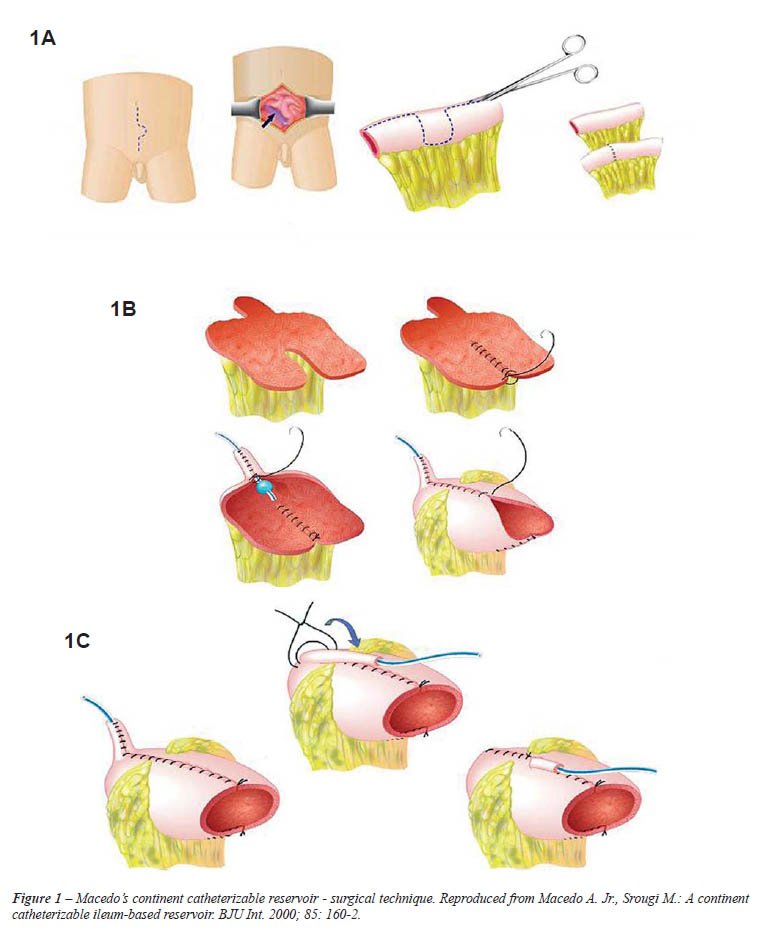

The technique consists of a continent catheterizable

ileum-based reservoir (3). A 30 cm segment of the distal ileum is isolated

and bowel continuity restored by end-to-end anastomosis. The detubularization

of the ileal segment follows the antimesenteric border of the intestine

up to the middle of the segment. Here the incision line continues transversally

to the anterior surface of the ileum, reaching the mesenteric border.

A 3 cm horizontal incision along the mesenteric side is continued before

returning to its usual direction at the antimesenteric border. The remainder

of the ileum is then opened longitudinally (Figure-1A). The 3 cm flap

from the anterior surface of the middle part of the ileum is mobilized

cranially, and tubularized around a 12F silicone Foley catheter (Figure-1B).

The continence valve mechanism is produced by embedding the tube over

a serous-lined extramural tunnel created by polypropylene 3/0 sutures

(Figure-1C). The distal end of the tube is anastomosed into a V-shaped

to the skin flap to avoid stomal stenosis. The reservoir is anastomosed

to the bladder or used as a substitute.

Surgical indications included patients with low bladder compliance and

capacity, filling detrusor pressure above 40 cm H2O, and/or urinary incontinence

that had failed to conservative management (CIC and anticolinergics).

Among the patients, 6 (26.08%) had posterior

urethral valve (PUV), 9 (39.13%) myelomeningocele, 4 (17.39%) bladder

exstrophy, 2 (8.69%) genitourinary rabdomyosarcoma, 1 (4.34%) spinal tumor

and 1(4.34%) had an ano-rectal anomaly (Table-1). Four patients (17.39%)

had undergone either a vesicostomy or nephrostomy prior to bladder augmentation.

One patient had bladder augmentation 14 months before kidney transplantation

(Table-1).

The procedure was performed with the ileum

in 21 patients (91.30%) and transverse colon in 2 patients (8.69%). The

colon was used in two cases of genitourinary rhabdomyosarcoma, due to

the risk of using a previous irradiated ileum to perform bladder substitution

(4). In only these two patients, the technique was used as a pouch whereas

in the others it was used as a bladder augmentation.

In one patient (4.34%), an antegrade left

colon enema procedure was performed in combination with bladder augmentation

due to fecal incontinence (5).

Two of the 21 patients (8.69%) underwent

a bladder neck procedure, due to persistent leakage and low detrusor leak

point pressure (6).

The patients’ medical records were

reviewed in order to define complication rates (acute and chronic), surgical

revision rate and final continence.

RESULTS

A perioperative complication

was observed in four patients consisting of one febrile urinary tract

infection, one partial operative wound dehiscence, one partial stomal

dehiscence and one vesico-cutaneous fistula after a secondary exstrophy

repair. This last patient, developed sepsis due to fungal infection and

did not survive.

The overall long-term complications rate

was 40.90% and consisted of two stomal stenoses (9.09%), one neobladder

mucosal extrusion (4.54%), three neobladder calculi (13.63%) and persistence

of urinary incontinence in three cases (13.63%), Table-2.

In the two cases of stomal stenosis, surgical revision was necessary in

both cases because progressive stomal dilatation failed.

The patient with neobladder mucosal extrusion

(4.54%) underwent redo closure and apendicovesicostomy.

Three patients presented with persistence

of urinary leakage (13.63%), two leaking through the stoma and one patient

through the urethra after failed bladder neck surgery. The patients with

stomal urinary leakage (9.09%) were reoperated: one patient underwent

a Monti procedure and the other a re-augmentation and they are currently

continent.

Three patients developed reservoir calculi

(13.63%), and underwent open cystolitotomy after failed endoscopic attempt.

All cases were found to have the calculi grown on a suture line presumably

associated to one of the seromuscular Prolene sutures of the tube valvular

mechanism.

One patient presented with late urinary

retention due to overdistention of the reservoir and tube outlet, and

a cystoscopy was necessary to help catheter passage through the stoma.

The overall surgical revision was 36.36%

and final continence rate was 95.45% with mean follow-up of 39.95 (9 to

91) months. The only incontinent patient was a complex exstrophy form

that failed a bladder neck procedure and is currently awaiting surgery

(Table-1).

COMMENTS

Successful continent abdominal

diversion requires a low pressure reservoir, a continent efferent channel

and a good cosmetic and non stenotic skin stoma.

The choice of the intestinal segment to

construct the reservoir is made according to surgeons’ experience,

but factors like incidence of electrolyte reabsorption and loss (acidosis

and alcalosis) certainly play a role in this procedure.

The creation of a continent catheterizable

conduit was initially described by Mitrofanoff, using the appendix as

a catheterizable stoma. Although the appendix is the most popular channel,

numerous other options have been reported (ureter, fallopian tubes and

tubularized colonic or bladder flaps) (7). In cases when the appendix

is absent, too short or has evidence of luminal stenosis, the search for

an alternative is imperative. The Yang-Monti procedure consists of using

a small segment of bowel (usually ileum) to create an efferent tube. A

2.0-2.5 cm segment of bowel is detubularized in the antimesenteric border

resulting in a tube of 6-7 cm in length, when transversely retubularized.

To date, the Yang-Monti technique is considered the substitute of choice

of the appendix for the Mitrofanoff principle (8).

In Mitrofanoff and Yang-Monti procedures,

when concomitant bladder augmentation or substitution is needed, two segments

of bowel must be prepared for creation of a neobladder and an efferent

tube. After that, both structures have to be joined together. The Macedo’s

continent catheterizable reservoir allows both procedures using the same

segment of the bowel. We recently performed an experimental study to define

the efficacy of the technique, in addition to other factors that may influence

continence of catheterizable channels using the principle of embedding

the outlet tube. From 20 pigs, colon specimens with 25 cm length were

obtained and a transverse flap in the average point of the intestine was

incised to create an efferent tube. A pressure study of both intra-luminal

surface and channel was then conducted during the filling, of the submersed

piece with environmental air in a water container, to define the efferent

channel continence. This study showed that angulation of channel with

colon, maintained by only one stitch was more important than a larger

extension of the valve, represented by 3 sutures in order to allow continence

to the efferent channel. This experimental study reproduced the clinical

situation in our patients and outlined the need of anchoring the reservoir

to the abdominal wall to retain the angulation of the stoma (9).

Leslie et al. (8) recently reviewed their

series of Monti urinary channels performed from 1997 to 2004. These authors

identified 168 patients with age of 10 months to 31 years at surgery.

Mean follow-up was 2, 6 years. In 168 patients, the ileum was used to

create the channel in 165 (98.2%), while sigmoid colon was used in the

other 3. A single Monti channel was created in 99 (58.9%) and a spiral

Monti in 66 (39.3%). A total of 37 open revisions were required (18.5%).Of

these 31 patients, 26 required only 1 open revision, 4 required 2 revisions,

and 1 patient required 3 revisions. Of the 152 patients, 148 were completely

continent (148 of 152 or 97, 4%), 1 had rare leakage, 2 had occasional

or intermittent leakage, and 1 continues to have frank leakage.

Thomas et al. (7) retrospectively reviewed

the continent catheterizable channel outcomes in their patients between

1998 and 2003. A total of 68 Mitrofanoff procedures were performed, using

appendix in 43% of cases, an ileal Yang-Monti tube in 38% and continent

cutaneous vesicostomy in 19%. Stomal stenosis occurred in 9 patients (13%)

within 1 to 24 months after surgery. False passages with catheterization

occurred in four patients (6%) with a mean follow-up of 6, 5 months. Of

the two patients with stomal stenosis both required surgical revision.

The final overall continence rate was 95.45%,

therefore similar to other series. Stomal leakage was found in two patients

(9.09%) requiring a surgical revision: redo procedure in one patient and

outlet channel revision (Monti tube) in the other. Both patients are presently

continent. The other case of urethral incontinence was an exstrophy patient

who is currently awaiting a second bladder neck procedure.

Persistent leakage and stomal complications,

mainly stenosis, are the most commonly reported pitfalls of continent

urinary diversion. Previous studies have examined the relationship between

stomal complications and type of conduit, type of reservoir, and type

and site of stoma. Stomal stenosis appears to be independent from all

of these variables (10).

It is well known that bladder augmentation

and catheterizable urinary diversion lead to an increased risk of urolithiasis.

Reasons for this include urinary stasis, mucus production, and chronic

bacteriuria. Our incidence of lithiasis was 13.63%, lower than other series.

At our institution, all parents are instructed to promote aggressive irrigation

of their children’s reservoir at least once every 24 hours with

100 to 150 mL of water. A nurse specialized in pediatric urology and stomal

care, monitors our patients regularly to make sure that parents follow

established guidelines.

Metcalfe et al. (11) published a series

of 500 bladder augmentations in children, revealing bladder stones formed

in 20 patients, 1% with a continent catheterizable channel compared to

10, and 3% without a channel. The increased risk of bladder calculi associated

with continent channels is in agreement with the study of Brough et al.

(12) which is probably due to incomplete emptying of the reservoir based

on nondependent catheterization. No difference in prevalence of stone

formation as regards ileal or sigmoid segments was reported.

Malignancy and enterocystoplasty is also

a growing concern and reports from pediatric bladder augmentation are

increasing in frequency. It is believed that the incidence of malignancy

will increase with longer follow-up. Pathogenesis likely involves nitrosamines

produced by bacteria in urine (13-15). Until the pathogenesis and the

etiology are better understood, the mainstay of prevention is regular

endoscopic surveillance. In the hope of preventing this disturbing event,

some authors have become more aggressive in managing recurrent urinary

tract infections and advocate annual surveillance cystoscopy to begin

at least 8 to 10 years after augmentation. The role of screening urinary

cytology has not been explored but it has merit and warrants further study

(11).

We recognize that our mean follow-up of

40 months is not long enough to speculate on long-term complications like

malignancy or nutritional deficits but this was not the scope of this

article. On the other hand, we believe that once a precise indication

for augmentation is established, it would make no difference in operating

the child after 5 years of within 3.6 years (mean age at present study).

It is important to stress that we are not advocating earlier surgery than

necessary but only reporting on clinical data retrospectively. We admit,

however, that this issue is controversial and many authors would argue

that they would leave patients with incontinent stomas or ureterostomies

until later on. We respect this argument but we regularly offer patients

both options and they in fact help us to decide which procedure to follow.

A second potential criticism on this paper

would be that early augmentation may increase work for the family simply

to achieve a goal (urinary continence) that other children of their age

have not yet reached. However, most of our data comprises patients with

myelomeningocele, posterior urethral valves and bladder exstrophy. As

we are aware, most of these patients are already undergoing CIC for preventing

upper urinary tract deterioration, so that excluding our 4 patients with

exstrophy, bladder reconstruction would not add much work in terms of

care, quite the contrary if we think that a abdominal stoma is much easier

to handle than performing urethral catheterization in wheel-chair bounded

children or boys with urethral sensitivity.

We would like to make clear that the scope

of this retrospective study was to look back in our bladder augmentation

database and evaluate if the rate of complications was higher in this

period of life. We are not advocating early surgery but this series comprises

a very complex population and most PUV and myelomeningocele patients had

upper urinary tract deterioration and recurrent urinary tract infection

and required treatment.

CONCLUSION

Our experience shows that continent catheterizable urinary diversion performed by Macedo’s technique is a safe procedure even in small patients below five years, guaranteeing renal function preservation, improvement in quality of life with an acceptable rate of complications. It is important that these patients and their parents have to be included in a nurse-assisted program of clean intermittent catheterization, and be stimulated to promote an adequate emptying of their reservoirs, diminishing the risks of bacteriuria, mucus production, lithiasis and stoma stenosis. Long-term results for children operated on under the age of 5 are still lacking but we do not expect much difference compared to that which is currently reported in the literature.

CONFLICT OF

INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Gilbert SM, Hensle TW: Metabolic consequences and long-term complications of enterocystoplasty in children: a review. J Urol. 2005; 173: 1080-6.

- Feng AH, Kaar S, Elder JS: Influence of enterocystoplasty on linear growth in children with exstrophy. J Urol. 2002; 167: 2552-5; discussion 2555.

- Macedo A Jr, Srougi M: A continent catheterizable ileum-based reservoir. BJU Int. 2000; 85: 160-2.

- Freitas RG, Nobre YT, Macedo A Jr, Demarchi GT, Ortiz V, Srougi M: Continent urinary reconstruction in rhabdomyosarcoma: a new approach. J Pediatr Surg. 2004; 39: 1333-7.

- Calado AA, Macedo A Jr, Barroso U Jr, Netto JM, Liguori R, Hachul M, et al.: The Macedo-Malone antegrade continence enema procedure: early experience. J Urol. 2005; 173: 1340-4.

- Macedo A Jr, Garrone G, Leslie B, Liguori R, Ottoni SL, Ortiz V: A new method to augment the bladder, provide a catheterizable stoma and reconstruct the bladder neck in one operation from a single intestinal segment: The technique step-by-step. J Ped Urol 2006; 2: 84. Abstract no 17.

- Thomas JC, Dietrich MS, Trusler L, DeMarco RT, Pope JC 4th, Brock JW 3rd, et al.: Continent catheterizable channels and the timing of their complications. J Urol. 2006; 176: 1816-20; discussion 1820.

- Leslie JA, Dussinger AM, Meldrum KK: Creation of continence mechanisms (Mitrofanoff) without appendix: the Monti and spiral Monti procedures. Urol Oncol. 2007; 25: 148-53.

- Vilela ML, Furtado GS, Koh I, Poli-Figueiredo LF, Ortiz V, Srougi M, et al.: What is important for continent catheterizable stomas: angulations or extension? Int Braz J Urol. 2007; 33: 254-61; discussion 261-3.

- Rapoport D, Secord S, MacNeily AE: The challenge of pediatric continent urinary diversion. J Pediatr Surg. 2006; 41: 1113-7.

- Metcalfe PD, Cain MP, Kaefer M, Gilley DA, Meldrum KK, Misseri R, et al.: What is the need for additional bladder surgery after bladder augmentation in childhood? J Urol. 2006; 176: 1801-5; discussion 1805.

- Brough RJ, O’Flynn KJ, Fishwick J, Gough DC: Bladder washout and stone formation in paediatric enterocystoplasty. Eur Urol. 1998; 33: 500-2.

- Soergel TM, Cain MP, Misseri R, Gardner TA, Koch MO, Rink RC: Transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder following augmentation cystoplasty for the neuropathic bladder. J Urol. 2004; 172: 1649-51; discussion 1651-2.

- Lane T, Shah J: Carcinoma following augmentation ileocystoplasty. Urol Int. 2000; 64: 31-2.

- Filmer RB, Spencer JR: Malignancies in bladder augmentations and intestinal conduits. J Urol. 1990; 143 :671-8.

____________________

Accepted

after revision:

March

10, 2009

_______________________

Correspondence

address:

Dr. Antonio

Macedo Jr.

Rua Maestro Cardim, 560 / 215

São Paulo, SP, 01323-000, Brazil

Fax: +55 11 3287-3954

E-mail: macedo.dcir@epm.br

EDITORIAL COMMENT

This retrospective series of children under age 5 years undergoing continent urinary diversion provides food for thought to readers. The short and long term complication rates, including stone formation, ongoing leakage, stomal stenosis and the need for further surgery are similar to those previously published from other centers regarding older patients. The surgical technique described is another novel variation of the Mitrofanoff principle. Clearly, the technical feasibility of performing this surgery in young patients has been established by the authors, but as they rightly point out, the necessity for such surgery at a young age remains debatable. The one death in their series, although perhaps a statistical aberration, speaks to the gravity of performing these procedures in young patients with often compromised reserves. Caution should be advised before considering continent urinary diversion as the standard approach to the young incontinent patient. These patients and their families are often well served with incontinent stomas, and pull-ups or pads until size, maturity and socialization mandate a surgical solution.

Dr.

Andrew E. MacNeily

BC Children’s Hospital

Vancouver, British Columbia

Canada

E-mail: amacneily@cw.bc.ca