RETROPERITONEOSCOPY

FOR TREATMENT OF RENAL AND URETERAL STONES

(

Download pdf )

RODRIGO S. SOARES, PEDRO ROMANELLI, MARCOS A. SANDOVAL, MARCELO M. SALIM, JOSE E. TAVORA, DAVID L. ABELHA JR

Section of Urology, Hospital da Previdência dos Servidores do Estado de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Objective:

To assess the efficacy of retroperitoneoscopy for treating stones in the

renal pelvis and proximal ureter.

Materials and Methods: In the period from

August 2003 to August 2004, 35 retroperitoneoscopies for treatment of

urinary stones were performed on 34 patients. Fifteen patients (42%) had

stones in the renal pelvis, and in 2 cases, there were associated stones

in the upper caliceal group. Twenty patients (58%) had ureteral stones,

all of them located above the iliac vessel. Twenty-five patients (71%)

had previously undergone at least one session of extracorporeal lithotripsy

and 8 patients (26%) also underwent ureteroscopy to attempt to remove

the stone. Eight patients underwent retroperitoneoscopy as a primary procedure.

Stone size ranged from 0.5 to 6 cm with a mean of 2.1 cm.

Results: Retroperitoneoscopy was performed

by lumbar approach with initial access conducted by open technique and

creation of space by digital dissection. We used a 10-mm Hasson trocar

for the optics, and 2 or 3 additional working ports placed under visualization.

Following identification, the urinary tract was opened with a laparoscopic

scalpel and the stone was removed intact. The urinary tract was closed

with absorbable 4-0 suture and a Penrose drain was left in the retroperitoneum.

In 17 patients (49%), a double-J stent was maintained postoperatively.

Surgical time ranged from 60 to 260 minutes with a mean of 140 minutes.

The mean hospital stay was 3 days (1-10 days). The mean length of retroperitoneal

urinary drainage was 3 days (1-10 days). There were minor complications

in 6 (17.6%) patients and 1 case of conversion due to technical difficulty.

Thirty-three patients (94%) became stone free.

Conclusion: Retroperitoneoscopy is an effective,

low-morbidity alternative for treatment of urinary stones.

Key

words: kidney calculi; ureteral calculi; surgery; laparoscopy;

retroperitoneal space

Int Braz J Urol. 2005; 31: 111-6

INTRODUCTION

Recent advances in extracorporeal lithotripsy and endoscopic techniques have made open surgery infrequent for treatment of urinary stones. However, patients with large impacted stones, especially those located in the proximal ureter, pose a challenge for treatment, often requiring multiple interventions. In such cases, open surgery remains a good, cost-effective alternative for resolution. The recent development of laparoscopic surgery has broadened the therapeutic options for several pathologies. The laparoscopic ureterolithotomy was initially described by Wickhan (1) in 1979, and more widely divulged since the early 1990s by Gaur (2), using the retroperitoneoscopic access. The present study reports the experience with retroperitoneoscopic ureterolithotomy and pyelolithotomy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Over

the period from August 2003 to August 2004, 34 patients ranging from 14

to 65 years of age (mean 32 years) underwent 35 retroperitoneoscopic interventions

for removal of urinary stones. Nineteen patients were male and 15 were

female. Twenty-four presented microscopic hematuria and/or lumbar pain,

4 patients had recurrent urinary infection and 5 patients were asymptomatic.

One patient presented obstructive acute renal failure with anuria and

anasarca due to bilateral stones.

In all patients, the diagnosis was confirmed

with imaging exams (plain abdominal x-ray, ultrasonography and excretory

urography or abdominal computerized tomography). Twenty-four patients

presented moderate or more pronounced hydronephrosis due to the presence

of stones. Two patients presented ureteropelvic junction stenosis with

associated stones. Two patients had complete ureteropelvic duplicity with

ureteral stones in the upper collecting system. Twenty-nine patients had

radiopaque stones and 5 had radiolucent ones. Stones were located on the

right side in 17 patients, on the left side in 16 patients, and 1 patient

had bilateral lithiasis.

Among the 34 patients, 31 had a single stone

and 3 had 2 or more stones or stone fragments. Twenty patients had ureteral

stones, with 14 located in the proximal ureter and 6 located in the middle

ureter. Fifteen patients presented renal stones, with 13 cases of single

pelvic stones and 2 cases of pelvic stones associated with stones in the

upper caliceal group. Twenty-five patients had previously undergone at

least 1 session of extracorporeal lithotripsy, and 7 patients also underwent

ureteroscopy in an attempt to remove the stone. One patient underwent

ureteroscopy only, which was unsuccessful. In 8 patients, retroperitoneoscopy

was indicated as the primary treatment. Eight patients presented previously

inserted double-J stents. One patient had a nephrostomy. Stone size ranged

from 0.5 cm to 6 cm in diameter (mean 2.1 cm).

The main indication for laparoscopy was

as an alternative to open and/or percutaneous surgery following failure

of extracorporeal lithotripsy and/or ureterolithotripsy. The condition

for indicating retroperitoneoscopy for ureteral stones was a location

above the iliac vessels, while the presence of an extra-renal or dilated

pelvis provided the condition for pelvic stones. The procedure was also

indicated in 2 cases with stones located in the upper calyx due to anatomical

aspects that favored extraction through the renal pelvis. Two patients

with UPJ stenosis underwent retroperitoneoscopic pyeloplasty during the

same surgical procedure. No patient presented previous lumbotomy. The

data for study analysis were collected retrospectively. All patients signed

an informed consent term.

Surgical Technique

The

procedure was a lumbar retroperitoneoscopic under general anesthesia in

all patients. In 5 cases, a double-J stent was positioned in retrograde

way during the immediate preoperative period. Patients were positioned

in the classic lumbotomy position with hyperextension. Access to the retroperitoneal

space was obtained with the open technique through a 1.5-mm subcostal

incision under the extremity of the 12th rib and muscle divulsion up to

the aponeurosis of the transverse muscle, which was then opened, and the

fascia transversalis, identifying the pre-renal fat. The creation of a

working space in the retroperitoneum was performed by digital dissection,

displacing the peritoneum medially without using a balloon. A Hasson trocar

was inserted in this space and fixed to the musculature with a purse-string

suture in order to avoid air leakage and development of subcutaneous emphysema,

and CO2 insufflation was performed until reaching 12-mm Hg tension. We

used 0-degree optics and, when needed, the working space was completed

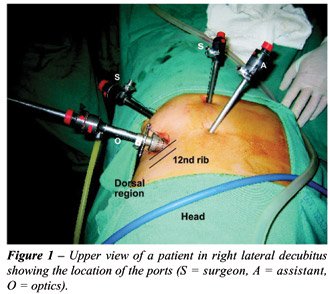

using the optics under visualization. Two additional trocars were placed

under visualization; a 5-mm trocar on the hemiclavicular line just above

the iliac spine and caudally to the optics port, and a 5- or 10-mm trocar

posterior to the optics at the posterior axillary line, forming a triangle.

Eventually, when retraction was required, another 5-mm trocar was placed

at an anterior position at the hemiclavicular line just below the costal

margin (Figure-1).

The ureter was initially identified in its

middle portion within the retroperitoneal fat and dissected up to the

level of the UPJ. Identifying the stone was also relatively easy in cases

with upstream dilation of the urinary tract. Two cases required the use

of radioscopy. The accurate location of the intra-ureteral stone was achieved

by palpation with laparoscopic forceps.

In the majority of cases, the urinary tract

was opened with a longitudinal incision using a laparoscopic scalpel.

At the beginning of our experience, due to the unavailability of tools,

the opening was performed using laparoscopic scissors or diathermy and

a metallic curve needle held by laparoscopic forceps. Stone extraction

was performed using laparoscopic forceps only. In both cases with stones

in the upper caliceal group, the stone was extracted with a rigid nephroscope

inserted through an Amplatz sheath placed at the incision site for the

optic port after removing the Hasson trocar. The nephroscope was guided

to the renal pelvis by a guide wire that had been previously positioned

through pyelotomy and the stone was removed using transnephroscopic forceps

under saline solution irrigation. In cases where it was feasible, the

stone was immediately removed from the cavity using the inner area of

one of the trocars without contacting the wall. Large stones were temporarily

kept in the retroperitoneal space and, at the end of the surgery, the

stone was introduced into a bag made out of a surgical glove and then

removed.

The double-J stent was positioned during

the surgical procedure in 9 cases, during the immediate peroperative period

by retrograde approach in 5 cases and during the peroperative period by

antegrade approach in 4, using a guide wire through one of the 5-mm ports.

The indication for inserting the stent in the peroperative period was

if there was complete obstruction of the urinary tract due to a long-term

impacted stone or the technical difficulty of achieving a satisfactory

closure of the renal pelvis or ureter at the beginning of our experience.

Suture of the urinary tract was performed

in all cases, except, due to technical difficulties, in one case of pyelolithotomy.

In the first 10 cases, closure was performed with single stitches using

non-absorbable 4-0 polyglycolic acid sutures; the other cases used 4-0

chromic catgut. Eventually the continuous suture was performed in wider

pyelotomies. A Penrose drain was placed in the retroperitoneum and exteriorized

through one of the port incisions, and was subsequently removed when the

drainage was lower than 30 mL/24 hours. The ureteral catheter was removed

on average 3 weeks after the procedure and a radiographic control was

performed around the 30th postoperative day.

RESULTS

Stone

removal using the retroperitoneoscopic approach was successfully accomplished

in 33 of the 35 interventions. In one case, conversion to open surgery

was required due to technical difficulties. In another case of ureteral

stone with a previously inserted double-J stent, it was impossible to

locate the stone even with radioscopic aid. This patient subsequently

underwent a new ureterosocopy, achieving stone removal.

Surgical time ranged from 60 min to 260

min (mean 140). Peroperative bleeding was negligible, except in 2 patients

that presented bleeding of approximately 500 mL due to damage to the left

gonadal vein and 1 parietal artery, respectively. In both cases, bleeding

was controlled without requiring conversion to open surgery. One patient

presented a voluminous retroperitoneal hematoma in the postoperative period,

which was treated conservatively. No case required blood transfusion,

the hospital stay ranged from 1 to 10 days (mean 3) and the follow-up

ranged from 2 to 12 months (mean 7). All patients became stone-free and

no case of urinary tract stenosis was observed during the follow-up.

The length of urinary drainage through the

Penrose drain ranged from 1 to 10 days (mean 3 days), being more prolonged

in cases where the urinary tract was not opened with laparoscopic scalpel,

in cases without double-J stent and in 1 case with double-J stent and

in 1 case where the pyelotomy was not sutured. In 2 cases with abundant

postoperative drainage, the postoperative insertion of a double-J stent

allowed the closure of the fistula in 1 day. Postoperative complications

occurred in 6 (17.6%) patients. Two patients presented an abscess at the

port site where the Penrose drain was exteriorized. One patient who had

previous nephrostomy developed urinary sepsis during the postoperative

period following inadvertent removal of the nephrostomy and improved after

inserting a retrograde ureteral catheter. One patient evidenced retroperitoneal

hematoma and was treated conservatively. One patient presented pain and

paresthesia in the ipsilateral lumbar region due to a thermal lesion of

the intercostal nerve during efforts to control the bleeding of the intercostal

artery, and was clinically managed. Another patient presented subcutaneous

emphysema due to subcutaneous insufflation of CO2 with no clinical repercussions.

COMMENTS

Despite

the development of extracorporeal lithotripsy and advancements in endoscopic

techniques for treatment of urinary stones, some patients still undergo

open surgery (3). The main surgical indications in our setting result

from failure and/or unavailability of minimally invasive techniques. The

recent advancement of laparoscopy in the urologic field has permitted

a new alternative for treatment of stones (4).

Traditionally the access for stone removal

in open surgery is achieved by retroperitoneal approach. Some authors

advocate laparoscopic surgery for managing stones using the intraperitoneal

approach (4-7) since it has the advantage of providing a larger working

space. The retroperitoneoscopic approach spread widely following the use

of a balloon for creating a working space in a study developed by Gaur

(2,8). This approach provides direct access to the urinary tract and avoids

manipulation and contact of urine with the intraperitoneal organs. The

main disadvantage of retroperitoneoscopic access is the smaller working

space, which renders reconstructive procedures such as suturing of the

urinary tract more difficult (8). In our experience, the use of a balloon

was not required for creating the retroperitoneal space. Using only digital

dissection and complementing the dissection with the optic itself when

required, we obtained a space that allowed us to fully perform the procedure

with satisfactory laparoscopic sutures. Positioning the surgeon’s

working ports caudally to the optics makes the procedure easier.

The lumbar retroperitoneoscopic approach

allows a fast and direct access to the urinary tract from the renal pelvis

to the ureter at the level of the iliac vessels. In favorable conditions,

it is possible to obtain access to stones located in caliceal groups,

especially the upper groups, through the renal pelvis. In 2 cases it was

possible to extract upper caliceal stones using a rigid nephroscope that

was inserted through an opening in the renal pelvis. Those cases had dilated

calices and wide infundibulum, which made the procedure easier. The combination

of laparoscopic and percutaneous nephrolithotripsy techniques has already

been described, especially for treating stones in ectopic kidneys (9).

However, the present study shows the possibility of successfully combining

these 2 techniques to extract caliceal stones in selected cases. The possibility

of accessing the stones using a transpelvic approach reduces the risk

of bleeding compared to the transparenchymal approach. This is an advantage

of retroperitoneoscopy over percutaneous nephrolithotomy. The selection

of patients with extra-renal and/or a dilated renal pelvis was fundamental

for obtaining good results with the retroperitoneoscopy. Another advantage

is the possibility of removing the stone intact with no fragmentation

and, thus, lower the risk of residual fragments. In all cases in this

series the stone was extracted intact, even in cases where the stone measured

more than 5 cm. At the moment, few studies have been published comparing

the classic open approach with retroperitoneoscopy (10). Other studies

are still required in order to assess each method’s advantages;

however, the advancement in laparoscopic techniques and instruments enables

us to widen the applications of retroperitoneoscopy (11,12).

Flexible urethroscopes or even flexible

cystoscopes using lasers (13-15) can also be used as a resource for application

by retroperitoneoscopic approach, similarly to what was performed in our

study with the rigid nephroscope, thus increasing the device’s scope

and the chances of success in selected cases.

Whether to use the ureteral catheter or

not is a controversial issue in urinary stone surgery (16). The presence

of a double-J stent makes identification of the ureter in the retroperitoneum

easier, however it makes the identification of the stone difficult since

it reduces the dilation of the urinary tract, and they can be easily mistaken

because of the stent’s rigidity. In one case from this series, in

a patient with a radiolucent ureteral stone, the presence of a previously

inserted double-J stent prevented the stone from being located.

In cases with anatomic changes to the urinary

tract, the laparoscopy represents a safe and effective alternative to

endoscopic procedures, which are often laborious and risky in such cases.

In 2 cases with pyeloureteral duplicity, the laparoscopic access enabled

easy localization and extraction of the stone after ureteroscopy efforts

had been frustrated. Similarly, in 2 cases with ureteropelvic junction

stenosis associated with stones in the dilated pelvis, laparoscopy enabled

easy stone extraction, and reconstruction with pelvic reduction, reproducing

the conventional open surgery (17).

Laparoscopy is a method that reproduces

the steps of open surgery and can be indicated as an alternative in cases

of therapeutic failure using less invasive methods (18,19). However, in

cases where the risk of failure using such method is high, such as anatomic

anomalies and voluminous and impacted ureteral stones, laparoscopy can

be indicated as a primary procedure (8). In cases of pelvic stones, the

retroperitoneoscopic pyelolithotomy is an alternative that allows the

removal of the intact stone with lower risk of residual fragments and

without requiring transparenchymal access, thus reducing the risk of bleeding.

REFERENCES

- Wickham JEA: The Surgical Treatment of Urinary Lithiasis. In Wickham JEA (ed.), Urinary Calculus Disease. New York, Churchill Livingstone. 1979; pp. 145-98.

- Gaur DD: Retroperitoneal laparoscopic ureterolithotomy. World J Urol. 1993; 11: 175-7.

- Assimos DG, Boyce WH, Harrison LH, McCullough DL, Kroovand RL, Sweat KR: The role of open stone surgery since extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. J Urol. 1989; 142: 263-7.

- Raboy A, Ferzli GS, Ioffreda R, Albert PS: Laparoscopic ureterolithotomy. Urology. 1992; 39: 223-5.

- Harewood LM, Webb DR, Pope AJ: Laparoscopic ureterolithotomy: the results of an initial series, and an evaluation of its role in the management of ureteric calculi. Br J Urol. 1994; 74: 170-6.

- Micali S, Moore RG, Averch TD, Adams JB, Kavoussi LR: The role of laparoscopy in the treatment of renal and ureteral calculi. J Urol. 1997; 157: 463-6.

- Keeley FX, Gialas I, Pillai M, Chrisofos M, Tolley DA: Laparoscopic ureterolithotomy: the Edinburgh experience. BJU Int. 1999; 84: 765-9.

- Gaur DD, Trivedi S, Prabhudesai MR, Madhusudhana HR, Gopichand M: Laparoscopic ureterolithotomy: technical considerations and long-term follow-up. BJU Int. 2002; 289: 339-43.

- Holman E, Toth C: Laparoscopically assisted percutaneous transperitoneal nephrolithotomy in pelvic dystopic kidneys: experience in 15 successful cases. J Laparoendosc Adv Sur Tech A. 1998; 8: 431-5.

- Goel A, Hemal AK: Evaluation of role of retroperitoneoscopic pyelolithotomy and its comparison with percutaneous nephrolithotripsy. Int Urol Nephrol. 2003; 35: 73-6.

- Gaur DD, Trivedi S, Prabhudesai MR, Gopichand M: Retroperitoneal laparoscopic pyelolithotomy for staghorn stones. J Laparoendosc Surg Tech A. 2002; 12: 299-303.

- Kaouk JH, Gill IS, Desai MM, Banks KL, Raja SS, Skarel M, et al.: Laparoscopic anathrophic nephrolithotomy: feasibility study in a chronic porcine model. J Urol. 2003; 169: 691-6.

- Chow GK, Patterson DE, Blute ML, Segura JW: Ureteroscopy: effect of technology and technique on clinical practice. J Urol. 2003; 170: 99-102.

- Kerbl K, Rehman J, Landman J, Lee D, Sundaram C, Clayman RV: Current management of urolithiasis: progress or regress? J Endourol. 2002; 16: 281-8.

- Landman J, Lee DI, Lee C, Monga M: Evaluation of overall cost and currently available small flexible ureteroscopes. Urology. 2003; 62: 218-22.

- Chew RH, Knudson BE, Deustedt JD: The use of stents in contemporary urology. Curr Opin Urol. 2004; 14: 111-5.

- Ramakumar S, Lancini V, Chan DY, Parsons JK, Kavoussi LR, Jarrett TW: Laparoscopic pyeloplasty with concomitant pyelolithotomy. J Urol. 2002; 167: 1378-80.

- Skrepetis K, Doumas K, Siafakas I, Lykourinas M: Laparoscopic versus open ureterolithotomy. A comparative study. Eur Urol. 2001; 40: 32-6.

- Goel A, Hemal AK: Upper and mid-ureteric stones: a prospective unrandomized comparison of retroperitoneoscopic and open ureterolithotomy. BJU Int. 2002; 89: 635-6.

_______________________

Received: October 6, 2004

Accepted after revision: January 13, 2005

_______________________

Correspondence address:

Dr. Rodrigo S. Quintela Soares

Rua Aluminio 50 / 31

Belo Horizonte, MG, 30220-090, Brazil

Phone: + 55 31 3222-2666

E-mail: quintelarod@yahoo.com