CHANGING

PROFILE OF PROSTATIC ABSCESS

(

Download pdf )

SURESH K. BHAGAT, NITIN S. KEKRE, GANESH GOPALAKRISHNAN, V. BALAJI, MARY S. MATHEWS

Department of Urology (SKB, NSK, GG) and Department Clinical Microbiology (VB, MSM), Christian Medical College, Vellore, India

ABSTRACT

Purpose:

To compare the clinical presentation of prostatic abscess and treatment

outcome in two different time frames with regards to etiologies, co-morbid

factors and the impact of multidrug resistant organism.

Materials and Methods: We retrospectively assessed

the charts of 48 patients with the diagnosis of prostatic abscess from

1991 to 2005. The period was divided arbitrarily into two different time

frames; phase I (1991-1997) and phase II (1998-2005). Factors analyzed

included presenting features, predisposing factors, imaging, bacteriological

and antibiotic susceptibility profile, treatment and its outcome.

Results: The mean patient age in phase I (n =

18) and phase II (n = 30) were 59.22 ± 11.02 yrs and 49.14 ±

15.67 respectively (p = 0.013). Diabetes mellitus was most common predisposing

factor in both phases. Eleven patients in phase II had no co-morbid factor,

of which nine were in the younger age group (22 - 44 years). Of these

eleven patients, five presented with pyrexia of unknown origin and had

no lower urinary tract symptoms LUTS Two patients with HIV had tuberculous

prostatic abscess along with cryptococcal abscess in one in phase II.

Two patients had melioidotic prostatic abscess in phase II. The organisms

cultured were predominantly susceptible to first line antibiotics in phase

I whereas second or third line in phase II.

Conclusion: The incidence of prostatic abscess

is increasing in younger patients without co-morbid factors. The bacteriological

profile remained generally unchanged, but recently multi drug resistant

organisms have emerged. A worrying trend of HIV infection with tuberculous

prostatic abscess and other rare organism is also emerging.

Key

words: prostate; infection; abscess; antibiotics; predisposing

factors

Int Braz J Urol. 2008; 34: 164-70

INTRODUCTION

The

incidence of prostatic abscess (PA) has declined markedly with the widespread

use of antibiotics and the decreasing incidence of urethral gonococcal

infections. Predisposing factors for PA include indwelling catheter, instrumentation

of lower urinary tract, bladder outlet obstruction, acute and chronic

bacterial prostatitis, chronic renal failure, hemodialysis, diabetes mellitus,

cirrhosis and more recently, the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (1,2).

The clinical diagnosis of PA has historically been regarded as difficult

because of the lack of pathognomonic symptoms or specific clinical signs.

With the advent of transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) (3) and computed tomography

(CT), the diagnosis of prostatic abscess has been greatly facilitated

(4,5).

The pathologic spectrum of PA ranges from

microabscesses that resolve with antimicrobial treatment alone to large

multilocular abscesses requiring drainage. Although rare prostatic abscess

can result in severe complications, including rupture into the periprostatic

space, urethra, rectum (rectourethral fistula), perivesical space, perineum,

as well as into the peritoneum and bladder due to either delayed diagnosis

or inadequate drainage (6-8).

The spectrum of organisms responsible for

the causation of prostatic abscess has changed. In the past, Neisseria

gonorrhoeae and Staphylococcus aureus were common (6), nowadays the most

common organisms responsible for PA have been gram-negative bacteria,

especially Escherichia coli (1,8,9). Recently, we encountered several

cases of PA caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae, Entererococci spp, Mycobacteria

spp and Burkholderia pseudomallei suggesting the possibility of a shift

in the pattern of causation of the disease that prompted us to review

the clinical and laboratory data therapeutic details on prostatic abscess

over a fourteen-year period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A

retrospective study was carried-out on 48 patients with prostatic abscess

diagnosed between June 1991 and June 2005. In order to determine changes

in disease pattern over time, the 14-year study period was arbitrarily

divided into two 7-year periods, phase I (1991 - 1997) and phase II (1998

- 2005). Institutional review board approval is not required for a retrospective

study in our country. The factors analyzed were age, presenting features,

digital rectal examinations, diagnostic imaging, associated co-morbidity,

bacteriological profile, antibiotic susceptibility pattern, treatment

modalities and its outcome during each phase. Urine samples were collected

as clean catch midstream voided sample and catheter specimen by sterile

technique. Pus from prostatic abscess was collected in a sterile culture

bottle during transurethral resection of the prostate or ultrasound guided

aspiration by aseptic technique. Identification of causative organisms

was performed by standard microbiologic methods (10). Antimicrobial susceptibility

testing was carried out using disk diffusion method (11). The interpretation

was based on the recommendations of Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute

(CLSI) (12). E. coli American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 25922, P.

aeruginosa ATCC 25922 and S. aureus ATCC 27853 were used as quality controls.

Statistical analysis was performed using

SPSS (Version 11.0) software. Age was compared using Mann-Whitney U Test

between the two phases. Other variables like lower urinary tract symptoms

(LUTS), acute urinary retention, pain localization, fever, chills, sepsis,

diabetes and digital rectal examination (DRE) findings, were compared

between the two phases using Chi-Square Test. All p values less than 0.05

were considered significant. The data are expressed as mean and ±

SD or median and range.

RESULTS

The

baseline data and clinical presentations in both the phases are shown

in Table-1. There was a recent statistically significant shift to younger

age at presentation (p = 0.013). The clinical presentations in both phases

were similar except LUTS and chills (Table-1). DRE measured size, tenderness

and induration and revealed similar findings in both phases.

Although the diabetes mellitus was the most

common factor in both phases, it was seen less frequently in phase II

(53.33%) than in phase I (77.77%) (Table-2). There were four patients

with no co-morbidity in phase I. There were 11 patients in phase II with

no co-morbid factor, of which nine were in the younger age group (22 -

44 years). Of these 11 patients five presented with pyrexia of unknown

origin (PUO) and the cause was prostatic abscess with no LUTS. There were

two patients with HIV infection, two with perinephric abscess and one

each with chronic liver disease and end stage renal disease in Phase II.

Urine culture was available in 13 of 18

patients in phase I and 28 of 30 patients in phase II (Table-3), it was

positive in 9 and 23 respectively. The pus culture was performed in eight

patients in phase I and 16 patients in phase II that was positive in two

and 14, respectively (Table-3). The urine culture and pus culture were

similar in only six cases. The organisms cultured were predominantly susceptible

to first line antibiotics (ampicillin, gentamicin, cotrimoxazole and quinolones)

in phase I whereas organisms were predominantly susceptible to second

line (amikacin, ceftazidime) or third line antibiotics (imipenem or meropenem),

in phase II. In phase I, of nine isolates four were E. coli and three

of them were sensitive to commonly used first line drugs (ampicillin,

ciprofloxacin, co-trimoxazole and gentamicin) and one was resistant. In

phase II , of nine E. coli isolates only two were sensitive to first line

antibiotics (ampicillin, cefuroxime, co-trimoxazole, gentamicin) and rest

7 were resistant and were susceptible to second line (amikacin, ceftazidime)

or third line antibiotics (imipenem and meropenem).

Of four Pseudomonas spp two were susceptible

to gentamicin and amikacin, and rests were susceptible only to ceftazidime,

imipenem and meropenem. Klebsiella spp was susceptible only to ceftazidime,

imipenem and meropenem. Burkholderia pseudomallei was susceptible only

to ceftazidime, imipenem and meropenem However, the susceptibility of

the gram positive organisms remained the same in both the phases.

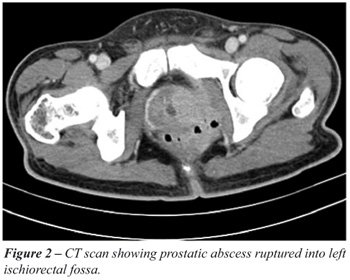

In phase I diagnosis was confirmed by abdominal

ultrasound in nine patients and transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) in three

whereas in phase II the common mode of diagnosis was TRUS in 17, trans-abdominal

ultrasound in six (Figure-1) and CT scan in one patient with perinephric

abscess and other two with ruptured prostatic abscess making it possible

to exactly define the extra-prostatic extent of pus in the ischiorectal

fossa and perirectal tissue (Figure-2).

The value of DRE in diagnosing prostatic

abscess remained the same in both phases demonstrated by the fact that

six patients in phase I and four in phase II were diagnosed based solely

on DRE.

As treatment, in addition to appropriate

antibiotics, in phase I, 10 patients underwent transurethral resection

of the prostate (TURP) along with transurethral drainage of pus, as they

were older and with symptoms of prostatic enlargement. Three patients

had TUR drainage, four had spontaneous rupture and one patient underwent

transperineal aspiration. In phase II, TUR drainage was the most common

mode of treatment, which was performed in 14 patients as patients were

of a younger age group, only four elderly patients with concomitant prostatic

enlargement had TURP. Three had TRUS guided aspiration, one with distal

penile urethral stricture had transperineal aspiration with statistical

process control and four had spontaneous rupture. Two patients with microabscesses

and one with melioidosis were treated exclusively with antibiotics. One

patient who underwent transperineal aspiration in phase II developed septic

shock requiring ventilatory and vasopressure support in intensive care

unit. None of the patients in phase I or phase II had septicemia due to

formal TURP and TUR drainage.

In phase I, four patients had spontaneous

rupture due to delayed diagnosis. One developed perineal abscess and one

pararectal abscess requiring open drainage, and in two patients abscesses

had ruptured into the prostatic urethra. In phase II, there were four

patients with spontaneous rupture due to delayed diagnosis. One developed

horse shoe perineal abscess that required open drainage and temporary

sigmoid colostomy. One had pararectal abscess that was managed by incision

and drainage. One had rectourethral fistula that was treated with antibiotic

and suprapubic drainage for three months. In one abscess ruptured into

the prostatic urethra. In phase II, there were two patients of HIV infection

with tuberculous prostatic abscess, along with tuberculous pyocele and

Cryptococcus neoformans isolated on pus culture in one.

All patients recovered well in both the

phases except one death in phase II who had melioidosis. Three young patients

in phase II following TUR drainage of prostatic abscess developed retrograde

ejaculation. Mean duration of hospital stay were similar in both the phases,

11.37 days (range 6 - 23 days) and 9.33 days (range 2 - 28 days ) as was

the duration of antibiotic therapy 28 days (14 - 42 days) and 30 days

(9 - 90 days) in phase I and phase II respectively.

COMMENTS

Prostatic

abscess is an infrequent condition in the modern antibiotic era with an

incidence of 0.5% to 2.5% of all prostatic disease (8). Prostatic abscess

can occur in patients of any age but is mainly found in men in their 5th

and 6th decade of life (13). As seen in our series, prostatic abscess

is occurring in a younger age group.

Predisposing factors for development of

prostatic abscess are diabetes mellitus, bladder outlet obstruction, indwelling

catheter, chronic renal failure, patients on hemodialysis, chronic liver

disease and more recently HIV infection (14). In our series, diabetes

was the most common predisposing factor, with HIV causing tuberculous

abscesses, in two patients. In phase II 53% of patients were diabetic.

They were younger and keeping with the WHO report (15) of diabetes occurring

in younger individuals in the Indian subcontinent. Three patients (21.42%)

in phase I and 7 patients(43.75%) in phase II were diagnosed to be diabetic

for the first time when they presented with prostatic abscess. This could

be a major new form of presentation in keeping with the increased incidence

of diabetes.

Prostatic abscess should be considered as

a possible etiology when evaluating for PUO in younger men as five of

11 patients without predisposing factor presented with PUO.

The clinical diagnosis of prostatic abscess

is sometimes difficult because of nonspecific symptoms (8). This condition

usually presents as an irritative voiding symptoms, perineal pain, and

fever and occasionally as acute urinary retention (1). In our series,

17 patients (94.44%) in phase I and 22 patients (73.33%) in phase II presented

with irritative LUTS. This may be due to the fact that patients were of

the older age group in phase I than in phase II. The patients with prostatic

abscess presented more commonly with fever and chills in phase II than

in phase I. The number of patients with sepsis was higher in phase II

(36.67%) than in phase I (22.2%). This is most probably due to infection

caused by multi drug resistant bacteria related to the misuse of antibiotics

in the community. In our series in phase I, 75% of E. coli were sensitive

to commonly used first line drugs (ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, co-trimoxazole

and gentamicin) and in phase II, more than 75% of E. coli were resistant

to first line antibiotics and were susceptible to second line (amikacin,

ceftazidime) or third line antibiotics (imipenem and meropenem).

The microbiology of prostatic abscess has

undergone a complete metamorphosis in the antibiotic era. More recently,

various reports have shown that the common organisms causing prostatic

abscess are E. coli and other enteric gram negative bacilli (1,8,9). More

recently we have reported two cases of prostatic abscess due to Burkholderia

pseudomallei (16).

However, the prevalence of immunocompromised

individuals has increased in the modern era (phase II), and the potential

for uncommon fastidious pathogens, particularly mycobacterial, fungal

and anaerobic pathogens, melioidosis, in addition to typical gram-negative

bacilli, will make the diagnosis of prostatic abscess more complicated

(14,16,17).

Surprisingly urine culture and pus culture

isolates were similar in only six cases (all in phase II). Of these, 4

were gram negative bacilli, this includes E. coli (n = 2), Klebsiella

spp (n = 1) and Pseudomonas spp (n = 1) and 2 were gram positive cocci

(S. aureus). Of six patients, five were diabetic and four had sepsis at

presentation. It is important to send material for culture (pus, urine,

and/or prostatic chips) in order to identify the etiologic agent, especially

in immunocompromised patients because they usually present with uncommon

microorganisms (18). Urine culture may be negative unless the abscess

ruptures into urethra or bladder. Thus it is important to emphasize that

pus culture and sensitivity should be performed routinely for management

of prostatic abscess.

Although the bacteriological profile was

similar in both phases, it is important to note that the antibiotic susceptibility

profile had changed, with organisms resistant to first line drugs and

sensitive only to higher antibiotics.

In our series, trans-abdominal USG was the

most common modality of diagnosis in phase I, but in phase II, TRUS became

the major diagnostic tool and was performed in 56.67% of patients and

has now become a standard protocol as the transrectal probe was acquired

later part of 1st phase.

Prostatic abscess currently occurring in

a relatively younger population has treatment implications. Transurethral

drainage could result in retrograde ejaculation as seen in three patients

in this series and hence one would like to resort to transperineal / transrectal

aspiration. TURP is indicated in elderly patients with associated bladder

outlet obstruction due to prostatic enlargement. In our series, in phase

I most of the patients being older with associated obstructive LUTS had

a formal TURP, in addition to drainage and the abscess. In phase II, 50%

of patients were treated by transurethral drainage of abscess, 3 patients

had TRUS guided aspiration where one required TUR drainage due to recurrent

prostatic abscess. In very few cases, open surgical drainage may be indicated

mainly in those patients with extraprostatic involvement (17). In this

series two patients with spontaneous rupture in each phase required open

surgical drainage.

Potential complications due to a late diagnosis

include spontaneous rupture into the urethra, perineum, bladder or rectum

and the development of septic shock with a mortality rate of 1% to 16%

(8). There was one mortality due to infection with melioidosis in this

series.

CONCLUSIONS

Prostatic abscess should be considered in the differential diagnosis of young men who present with pyrexia of unknown origin. It could be the primary presentation in a recently diagnosed diabetic. The incidence of prostatic abscess is increasing in younger males. This is probably related to the higher incidence of diabetes in younger males in this region. Clinical findings could be subtle especially in younger men who may not present with LUTS. While the bacteriology remains largely unchanged, the emergence of multi drug resistant organisms points to the rampant misuse of antibiotics. The emergence of HIV brings the added concern that some of the abscesses could be the result of tuberculous infection.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Angwafo FF 3rd, Sosso AM, Muna WF, Edzoa T, Juimo AG: Prostatic abscesses in sub-Saharan Africa: a hospital-based experience from Cameroon. Eur Urol. 1996; 30: 28-33.

- Leport C, Rousseau F, Perronne C, Salmon D, Joerg A, Vilde JL: Bacterial prostatitis in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Urol. 1989; 141: 334-6.

- Cytron S, Weinberger M, Pitlik SD, Servadio C: Value of transrectal ultrasonography for diagnosis and treatment of prostatic abscess. Urology. 1988; 32: 454-8.

- Davidson KC, Garlow WB, Brewer J: Computerized tomography of prostatic and periurethral abscesses: 2 case reports. J Urol. 1986; 135: 1257-8.

- Vaccaro JA, Belville WD, Kiesling VJ Jr, Davis R: Prostatic abscess: computerized tomography scanning as an aid to diagnosis and treatment. J Urol. 1986; 136: 1318-9.

- Sargent JC, Irwin R: Prostatic abscess: a clinical study of 42 cases. Am J Surg. 1931; 11: 334-7.

- Mitchell RJ, Blake JR: Spontaneous perforation of prostatic abscess with peritonitis. J Urol. 1972; 107: 622-3.

- Granados EA, Riley G, Salvador J, Vincente J: Prostatic abscess: diagnosis and treatment. J Urol. 1992; 148: 80-2.

- Jacobsen JD, Kvist E: Prostatic abscess. A review of literature and a presentation of 5 cases. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1993; 27: 281-4.

- Myer’s and Koshi’s Manual of Diagnostic Procedure in Medical Microbiology and Immunology/Serology. Faculty, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Christian Medical College, Vellore, India. Pondicherry, All India Press, 2001.

- Bauer AW, Kirby WM, Sherris JC, Turck M: Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am J Clin Pathol. 1966; 45: 493-6.

- Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (formerly, National committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance Standards for Antimicrobials Disc Susceptibility Tests. 8th ed. Approved Standards NCCLS Document M2-A7, Wayne, PA: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, 2000.

- Pai MG, Bhat HS: Prostatic abscess. J Urol. 1972; 108: 599-600.

- Trauzzi SJ, Kay CJ, Kaufman DG, Lowe FC: Management of prostatic abscess in patients with human immunodeficiency syndrome. Urology. 1994; 43: 629-33.

- Mohan V, Deepa M, Deepa R, Shanthirani CS, Farooq S, Ganesan A, et al.: Secular trends in the prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in urban South India--the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES-17). Diabetologia. 2006; 49: 1175-8.

- Viswaroop BS, Balaji V, Mathai E, Kekre NS: Melioidosis presenting as genitourinary infection in two men with diabetes. J Postgrad Med. 2007; 53: 108-10.

- Ludwig M, Schroeder-Printzen I, Schiefer HG, Weidner W: Diagnosis and therapeutic management of 18 patients with prostatic abscess. Urology. 1999; 53: 340-5.

- Oliveira P, Andrade JA, Porto HC, Pereira Filho JE, Vinhaes AF: Diagnosis and treatment of prostatic abscess. Int Braz J Urol. 2003; 29: 30-4.

____________________

Accepted after revision:

March 6, 2008

_______________________

Correspondence address:

Dr. Ganesh Gopalakrishnan

Department of Urology

Christian Medical College

Vellore, S. India

Fax: + 914 162 232-103

E-mail: ganeshgopalakrishnan@yahoo.com