RADICAL

PROSTATECTOMY: EVOLUTION OF SURGICAL TECHNIQUE FROM THE LAPAROSCOPIC POINT

OF VIEW

(

Download pdf )

doi: 10.1590/S1677-55382010000200002

XAVIER CATHELINEAU, RAFAEL SANCHEZ-SALAS, ERIC BARRET, FRANCOIS ROZET, MARC GALIANO, NICOLAS BENOIST, OLEKSANDR STAKHOVSKY, GUY VALLANCIEN

Department of Urology, Institut Montsouris, Université Paris Descartes, Paris, France

ABSTRACT

Purpose:

To review the literature and present a current picture of the evolution

in radical prostatectomy from the laparoscopic point of view.

Materials and Methods: We conducted an extensive

Medline literature search. Articles obtained regarding laparoscopic radical

prostatectomy (LRP) and our experience at Institut Montsouris were used

for reassessing anatomical and technical issues in radical prostatectomy.

Results: LRP nuances were reassessed by

surgical teams in order to verify possible weaknesses in their performance.

Our basic approach was to carefully study the anatomy and pioneer open

surgery descriptions in order to standardized and master a technique.

The learning curve is presented in terms of an objective evaluation of

outcomes for cancer control and functional results. In terms of technique-outcomes,

there are several key elements in radical prostatectomy, such as dorsal

vein control-apex exposure and nerve sparing with particular implications

in oncological and functional results. Major variations among the surgical

teams’ performance and follow-up prevented objective comparisons

in radical prostatectomy. The remarkable evolution of LRP needs to be

supported by comprehensive results.

Conclusions: Radical prostatectomy is a

complex surgical operation with difficult objectives. Surgical technique

should be standardized in order to allow an adequate and reliable performance

in all settings, keeping in mind that cancer control remains the primary

objective. Reassessing anatomy and a return to basics in surgical technique

is the means to improve outcomes and overcome the difficult task of the

learning curve, especially in minimally access urological surgery.

Key

words: prostatectomy;

laparoscopy; minimally invasive; outcomes

Int Braz J Urol. 2010; 36: 129-40

INTRODUCTION

Radical

prostatectomy (RP) remains the gold standard for the surgical treatment

of localized prostate cancer. Evolution of the technique was started by

the pioneering work done by Walsh and Donker (1). The accurate description

of the dorsal vein complex, pelvic plexus and cavernous nerves and pelvic

fascia has had a real impact in a number of patients operated for prostate

cancer as regards morbidity and mortality procedure and scientific investigation

in prostatic carcinoma (2). Schuessler et al. (3) described their initial

experience in laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (LRP), which they initially

considered as having no benefits when compared to its open surgery counterpart.

However, they rationalized that technical progress and experience could

improve results. In 1998, the Montsouris team began their experience in

LRP with their own developed technique. LRP technique was well standardized

(4); however, changes have been gradually introduced as a natural evolution

of our surgical performance. The objective was to meet the demanding oncologic

and functional objectives of the procedure and verify the efficacy of

our technique. Our aim was to update the latest advances in our technique

for LRP, at a point where our team had evolved from the steep learning

curve of the procedure and arrived at a plateau level in which revaluation

and improvement became mandatory.

UNDERSTANDING THE ANATOMY

OF THE PROSTATE AND ITS IMPLICATIONS ON SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Whether RP is performed in open surgery, laparoscopic or perineal, the anatomy of the gland remains the cornerstone of surgery. Comprehensive understanding of the anatomical landmarks and its implications in the patient’s future quality of life are mandatory when attempting the procedure. This issue has propelled a rather wide range of surgical descriptions that subsequently produced a controversy in the anatomic nomenclature. In fact, the endopelvic fascia is also described as: lateral pelvic fascia or parietal layer of the pelvic fascia; the levator fascia is mentioned as outer layer periprostatic fascia and the prostatic fascia is also known as inner layer of periprostatic fascia (5). Furthermore, the arrival of laparoscopy presented the possibility of a magnified surgical field that has allowed urologic surgeons to verify prostatic anatomy and this has also contributed to extensive discussion (6).

OPTIMAL SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Once the surgical field has been developed, as described by Barré, RP can be summarized in the stages described in Table-1 (7). Laparoscopic and robotic approaches have specific variations, which are shown in Table-1.

We are still far from the well known “Trifecta” ideal combination

of oncologic success and adequate continence and potency (8), because

even when patients should be comprehensively selected for surgery, a great

number of particular variations still remain for each patient, including:

large prostate, post transurethral resection setting and the obese patient.

The best performances of RRP or LRP show a 11-14% of positive margins,

in 50 to 70% of patients with early continence and a maximum of 70% of

patients with potency at one year follow-up (4-8).

CONTINENCE PRESERVATION

TECHNIQUE

Ligation of the Dorsal Vein

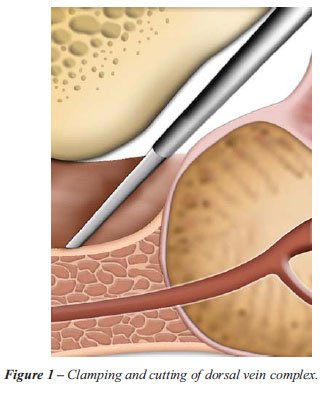

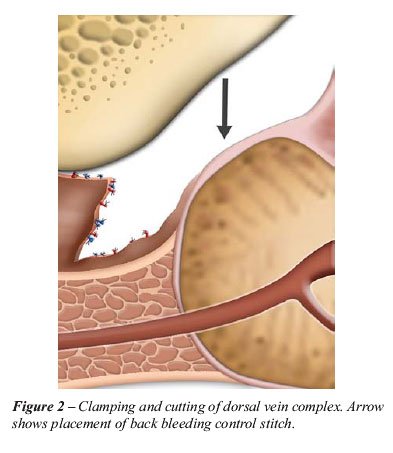

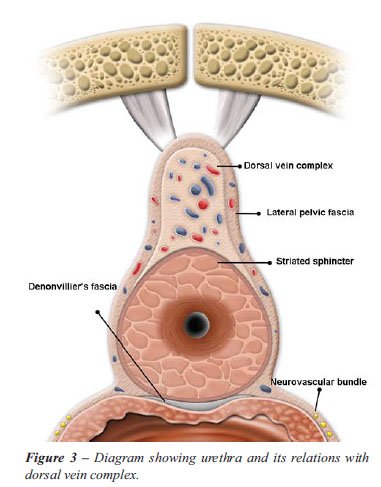

The dorsal vein complex (DVC) approach, aims to reduce blood loss and also to improve functional continence results. As described by Olerich (9), the sphincter complex (SC) responsible for passive urinary control, covers the prostate apex. Therefore, DVC and SC are parallel and transection of the DVC could eventually be excised at the anterior portion of the sphincter with a definite impact in postoperative continence improvement (10,11). For that reason, careful and elective ligation should be achieved in order to expose the prostatic apex and urethra (Figures-1 and 2).

Dissection of the Apex

Apex dissection

should be approached with the idea of avoiding both areas by leaving prostatic

tissue behind and not damaging the striated sphincter. Once the endopelvic

fascia is incised and the puboprostatic ligaments transected, careful

dissection to free the muscle fibers from the apex should be performed.

Careful observation of the shape of the prostate is important to delineate

the borders and therefore guide dissection (2,7), keeping in mind that

at the apical region nerve fibers run at 3 and 9 o’clock positions

posterolaterally to the urethra (11) (Figure-3).

Nguyen et al. (12) have proposed posterior reconstruction of Denonvilliers’

musculofascial plate (PRDMP) to enhance early continence after robotic

or laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. These authors suggest that PRDMP

leads to improved maintenance of membranous urethral length and significantly

higher early continence rates.

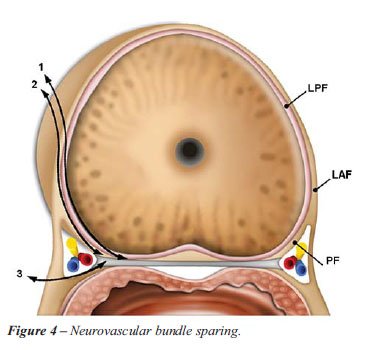

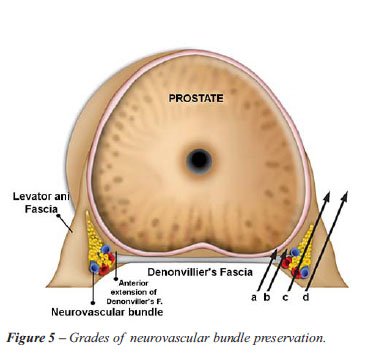

NERVE SPARING TECHNIQUE: MARGINS VS. POTENCY. ON WHICH SIDE OF THE FASCIA

DO WE STAND?

Walsh

et al. have stated that: “The Lateral fascia is divided into 2 layers

- the prostatic fascia and the levator fascia- and when the nerve sparing

is properly performed the prostatic fascia must remain on the prostate”

(13). The distinction between intrafascial, interfascial and extrafascial

dissection has been described by open surgery surgeons (1,7), however

there is still controversy as to whether or not a clear distinction of

the layers of tissue can be accomplished by open surgery, even by using

operating loupes (6). As described by Martínez-Piñeiro et

al., (14) the interfascial plane would be a plane between the prostatic

fascia and Denonvilliers fascia posterior and between the prostatic fascia

and the anterior extension of Denonvilliers’ fascia at the posterolateral

aspect of the prostate.

In our experience, we have been able to

obtain a highly detailed view of the anatomy with the endoscopic approach

and more recently, lenses provided by the robotic interface do in fact

improve the surgical field due to a three-dimensional perspective. Although

the improvements accomplished since Walsh’s first operation over

25 years ago, radical prostatectomy remains a challenging procedure with

a steep learning curve and two objectives that are contradictory. The

idea is to obtain reliable cancer control, which means avoidance of positive

surgical margins while preserving as much as possible functionality in

terms of continence and potency. Excellent rates of cancer control for

patients with organ-confined disease (5-year recurrence free probabilities

close to 100%) are accomplished by dedicated surgeons only when a surgical

technique is properly performed (15). Complete preservation of the neurovascular

bundles (NVB) is performed either with intrafascial or interfascial dissection

technique (6), however, we believe that the interfascial plane would be

the elected plane for comprehensive nerve sparing in order to be oncologically

safe while preserving functionality (Figures-4 and 5). Secin et al., (16)

have described the intrafascial technique as the reference procedure for

preservation of NVB in selected patients based on pre- and intraoperative

findings. Several authors have also supported the idea of an intrafascial

dissection (17-19). We agree that comprehensive and judicious preoperative

evaluation and adequate interpretation of operative findings are crucial

in final results of the prostatectomy, but there is also a need to state

a technical approach that might not only spread LRP even more, but offer

safety to patients in all settings. See Table-2 for variations on technique,

approach and type of nerve sparing technique for radical prostatectomy.

Antegrade and Retrograde Dissections

There are two nerve sparing techniques, the antegrade dissection that starts at the base of the prostate and continues along the posterolateral contour to end in the posterior edge (7,20), and the retrograde, which starts at the apex and develops a plane between the rectum and the prostate to expose the medial border of the NVB. Retrograde dissection was the initially described technique for RRP, and it is characterized by a high incision of the fascia. The antegrade dissection has been applied primarily in LRP and it has been criticized because of the starting point of dissection that can be rather high, creating an intrafascial dissection, or very low, which would injure the nerves (7). In the principles of interfascial dissection of the NVB, skilled dissection and avoiding energy sources around the NVB are more important factors than the nerve-preservation technique used (20).

ANATOMICAL RATIONALE

FOR A PROSTATIC VEIL

There is objective evidence that supports the fact of the existence of a neurovascular network that surrounds the prostate and that it could have an impact in postoperatory evaluated issues. However, the idea of giving it a cumbersome name, has just add more to the already crowded world of nomenclature in radical prostatectomy and therefore we agree with Rassweiler [5] to avoid using the so-called term “Veil of Aphrodite”. Ganzer et al. (21) have objectively verified that the highest percentage (74-84%) of the total nerve surface of the prostate is located dorsolaterally, with up to 39% of nerve surface area, found ventrolaterally. In their study, computerized planimetry offered a basic view that periprostatic nerve distribution is variable with a high percentage of nerves in the ventrolateral and dorsal position. They also verified an interesting decrease in total periprostatic nerve surface area from the base to the apex. Several researchers have also addressed the subject of periprostatic nerve distribution with comparable results in terms of most frequent localization of nerves (dorsolaterally) and a high percentage of variation from case to case (22-24).

ROBOTIC INTERFACE OFFERINGS FOR RADICAL PROSTATECTOMY LEARNING CURVE

As we have

previously mentioned, laparoscopic radical prostatectomy far from dying

is rapidly evolving (25). The use of the robot has reduced the learning

curve due to EndoWrist® technology, three-dimensional imaging and

magnification but there is still a need for solid evidence to back up

the analysis of the learning curve, as completing the procedure or being

able to perform it does not necessarily mean it is done well. The robot

represents a useful instrument for the surgeon and it should be regarded

as a procedure to be followed in the future, as its results will certainly

improve in the years to come.

Meanwhile, how many cases do we need to become expert surgeons in the

technique we perform on a daily basis? or perhaps more importantly, how

many cases do the fellows standing by our sides need to become safe and

reliable operators?

These remain controversial questions that we still need to address, not

only in radical prostatectomy but also as regards minimal urological access

surgery. The arrival of both, laparoscopy and more recently the robotic

interface has focused our attention on the term learning curve. In fact,

laparoscopic series brought with it a tremendous enthusiasm in terms of

validation of the technique and therefore extensive work in the procedure’s

learning curve.

Is there a formal definition for learning curve? Probably not. However,

let us see:

The Ross procedure is a challenging operation for patients with aortic

valve disease. The principle is to remove the patient’s normal pulmonary

valve and used it to replace the patient’s diseased aortic valve.

In Dr. Ross’s own series, 23% of the patients died during the first

year of the operation and 18% in the second year. In the following 10

years, the surgical mortality in a series of 188 patients dropped to 9%.

This is a learning curve. The message: It requires time and hard work

(26). The incorporation of new devices into surgical practice - such as

the robot - requires that surgeons acquire and master new skills. As in

any new technology, robotic surgery demands dedication to achieve expertise.

For a skilled laparoscopic surgeon the learning curve to achieve proficiency

with robotic radical prostatectomy is estimated at between 40 to 60 cases.

For the laparoscopically naive surgeon the curve is estimated at 80 to

100 cases (27). The Da Vinci assisted approach incorporates the advantages

of minimally invasive approach while presenting comparable results to

the open surgical approach. However, we do not believe that proficiency

could be achieved within the first 20 or 25 cases of robotic experience,

as has previously been stated (28). Robotic interface appears to offer

a significant benefit to the laparoscopically naive surgeon with respect

to learning curve, at an increased cost. We have previously demonstrated

that laparoscopic extraperitoneal radical prostatectomy is equivalent

to the robotic assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy in the hands of skilled

laparoscopic urological surgeons with respect to operative time, operative

blood loss, hospital stay, length of bladder catheterization and positive

margin rate (29). Improvement of our technique is found on a daily basis

and there is considerable experience needed to reach the best quality

in both open and laparoscopic standards. The latter is in agreement with

the study by Vickers et al. in their timely publication assessing surgical

learning curve for prostate cancer control (30). These investigators found

a statistical significance related to the surgeon’s experience and

cancer control after radical prostatectomy. This study is a return to

the basic concept of learning curves and suggests a real link between

surgical technique and cancer control. Its analysis showed a dramatic

improvement in cancer control with increasing surgeon experience up to

250 previous treated cases. As presented in a recent review of the robotic

literature by Ficarra et al., positive surgical margin rates decreased

with the surgeon’s experience and improvement in technique; reaching

percentages similar to those of retropubic and laparoscopic series (31).

Establishing a robotic prostatectomy program is an important challenge

to any institution requiring both financial support and a focused operating

room team (32), but this must not lead to an aggressive patient acquisition

(advertising, commercialization) during the basic learning curve, because

cancer care implies offering a product of the highest quality. The learning

curve plateaus come with training and experience. Surgeons have always

recognized a structured way to introduce new procedures and learning a

new technique requires dedication. Unfortunately, as reported by Tooher

et al., (33) the laparoscopic learning curve has only been addressed in

a limited number of studies.

NEED FOR REVISION AND STANDARDIZATION

As recently described, oncological outcomes after radical prostatectomy improve with the surgeon’s experience irrespective of patient risk and inadequate surgical technique leads to recurrence (34). It has been recently reported that patients undergoing minimally access prostatectomy (either pure lap or robotic assisted) vs. open radical prostatectomy (ORP) have a lower risk for perioperative complications and shorter lengths of stay, but they harbor higher probability for salvage therapy and anastomotic strictures (35). These unfavorable outcomes would be diminished by high surgical volume. The main limitation of this study was the comparison of surgical teams that do not necessarily represent the standard of care in both open and laparoscopic technique. Therefore, the aim is to improve LRP surgical technique and take advantage of the novel surgical instruments to guarantee a solid based concept of minimally access surgery as the most adequate therapeutic option for localized prostate cancer. As described by Touijer and Guillonneau (36) even when all the reports agree and demonstrate the benefits of minimal access surgery, there are no prospective series comparing LRP vs. ORP and there are important variations reported in the characteristics of the procedure: whether or not performing lymph node dissection, a wide range of positive margin rates (6% to 8% for organ-confined disease and from 35% to 60% with extraprostatic extension), lack of evaluation of short term biochemical recurrence and extreme variations in the evaluation and reporting of functional outcomes. Going back to basics, in our understanding, is a reevaluation and deployment of a surgical technique based on both the available knowledge of the subject and experience. Stolzenburg et al. have opened the way in this matter with their recent experience of extraperitoneal LRP with intrafascial dissection, in which they report a low frequency of surgical margins with 80% and 94% of potency and continence, respectively (37). However, Tooher et al. in their systematic review of comparative studies report that stronger evidence is needed when comparing LRP vs. RRP. There is still a desire in the medical community for a randomized control study and LRP still remains as the emerging alternative for the surgical treatment of localized prostate cancer (33).

LRP MONTSOURIS TECHNIQUE

Five trocars are used (three 5 mm, two 10 mm), one in the umbilicus and the others in the iliac fossa. There are no significant differences between the Trans- or extraperitoneal approach as we have previously described (38), however currently we usually perform an extraperitoneal approach with balloon dissection under direct visualization and insufflation of the space, which creates an optimal operative field. Trocars are positioned according to surgeon’s preference. Bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection is performed when it is indicated (PSA values > 10 ng/mL and Gleason score > 7 on primary prostatic biopsy) (39,40). In such cases, we rather perform a transperitoneal approach for the procedure. Table-3 shows a detailed description of the most recent surgical technique performed at our institution.

POINTS OF CHANGE. STAYS AND GOES

It has been over 25 years since the Walsh and Donker anatomical description and over 10 years since the Montsouris experience in LRP started. The rapid evolution of surgical technique has been the rule and several variations for RP have been described. After years of experience, we would like to share the elements of the operation that we have kept overtime and others that we have discarded.

Stays:

• Opening of the pelvic fascia.

• Preservation of the bladder neck for cases with negatives biopsies

at prostatic base.

• Effective hemostasis by means of small clips and elective micro

bipolar energy.

• Antegrade nerve sparing dissection.

Goes:

• Direct dissection of the seminal vesicles after incising the peritoneum

above the pouch of Douglas

• Deep stitching without clamping of the dorsal vein complex to

accomplish hemostasis.

• Extensive lateral dissection of the apex and urethra.

• Intrafascial dissection during nerve sparing.

CONCLUSIONS

Radical prostatectomy is a complex surgical operation with difficult objectives; surgical technique should be standardized in order to allow an adequate and reliable performance in all settings, keeping in mind that cancer control remains objective number one. There is no unique way to attain the highest surgical quality (open or lap, antegrade or retrograde, intra- or interfascial), but there are several concepts and rules to be followed. Reassessing anatomy and going back to basics in surgical technique is the path to improve outcomes and overcome the difficult task of learning curve.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Miss Julia Dasic performed the artistic work in the figures.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Walsh PC, Donker PJ: Impotence following radical prostatectomy: insight into etiology and prevention. J Urol. 1982; 128: 492-7.

- Walsh PC: The discovery of the cavernous nerves and development of nerve sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 2007; 177: 1632-5.

- Schuessler WW, Schulam PG, Clayman RV, Kavoussi LR: Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: initial short-term experience. Urology. 1997; 50: 854-7.

- Guillonneau B, Vallancien G: Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: the Montsouris technique. J Urol. 2000; 163: 1643-9.

- Rassweiler J: Intrafascial nerve-sparing laproscopic radical prostatectomy: do we really preserve relevant nerve-fibres? Eur Urol. 2006; 49: 955-7.

- Martínez-Piñeiro L: Prostatic fascial anatomy and positive surgical margins in laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2007; 51: 598-600.

- Barré C: Open radical retropubic prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2007; 52: 71-80.

- Bianco FJ Jr, Scardino PT, Eastham JA: Radical prostatectomy: long-term cancer control and recovery of sexual and urinary function (“trifecta”). Urology. 2005; 66 (5 Suppl): 83-94.

- Oelrich TM: The urethral sphincter muscle in the male. Am J Anat. 1980; 158: 229-46.

- Stolzenburg JU, Schwalenberg T, Horn LC, Neuhaus J, Constantinides C, Liatsikos EN: Anatomical landmarks of radical prostatecomy. Eur Urol. 2007; 51: 629-39.

- Heidenreich A: Radical prostatectomy in 2007: oncologic control and preservation of functional integrity. Eur Urol. 2008; 53: 877-9.

- Nguyen MM, Kamoi K, Stein RJ, Aron M, Hafron JM, Turna B, et al.: Early continence outcomes of posterior musculofascial plate reconstruction during robotic and laparoscopic prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2008; 101: 1135-9.

- Walsh PC, Lepor H, Eggleston JC: Radical prostatectomy with preservation of sexual function: anatomical and pathological considerations. Prostate. 1983; 4: 473-85.

- Martínez-Piñeiro L, Cansino JR, Sanchez C, Tabernero A, Cisneros J, de la Peña JJ: Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Differences between the interfascialand the intrafascial technique. Eur Urol Suppl. 2006; 5: 331

- Vickers AJ, Bianco FJ, Gonen M, Cronin AM, Eastham JA, Schrag D, et al.: Effects of pathologic stage on the learning curve for radical prostatectomy: evidence that recurrence in organ-confined cancer is largely related to inadequate surgical technique. Eur Urol. 2008; 53: 960-6.

- Secin FP, Serio A, Bianco FJ Jr, Karanikolas NT, Kuroiwa K, Vickers A, et al.: Preoperative and intraoperative risk factors for side-specific positive surgical margins in laparoscopic radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2007; 51: 764-71.

- Curto F, Benijts J, Pansadoro A, Barmoshe S, Hoepffner JL, Mugnier C, et al.: Nerve sparing laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: our technique. Eur Urol. 2006; 49: 344-52.

- Stolzenburg JU, Rabenalt R, Tannapfel A, Liatsikos EN: Intrafascial nerve-sparing endoscopic extraperitoneal radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2006; 67: 17-21.

- Menon M, Kaul S, Bhandari A, Shrivastava A, Tewari A, Hemal A: Potency following robotic radical prostatectomy: a questionnaire based analysis of outcomes after conventional nerve sparing and prostatic fascia sparing techniques. J Urol. 2005; 174: 2291-6, discussion 2296.

- Rassweiler J, Wagner AA, Moazin M, Gözen AS, Teber D, Frede T, Su LM: Anatomic nerve-sparing laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: comparison of retrograde and antegrade techniques. Urology. 2006; 68: 587-91; discussion 591-2.

- Ganzer R, Blana A, Gaumann A, Stolzenburg JU, Rabenalt R, Bach T, et al.: Topographical anatomy of periprostatic and capsular nerves: quantification and computerised planimetry. Eur Urol. 2008; 54: 353-60.

- Lunacek A, Schwentner C, Fritsch H, Bartsch G, Strasser H: Anatomical radical retropubic prostatectomy: ‘curtain dissection’ of the neurovascular bundle. BJU Int. 2005; 95: 1226-31.

- Kiyoshima K, Yokomizo A, Yoshida T, Tomita K, Yonemasu H, Nakamura M, et al.: Anatomical features of periprostatic tissue and its surroundings: a histological analysis of 79 radical retropubic prostatectomy specimens. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004; 34: 463-8.

- Eichelberg C, Erbersdobler A, Michl U, Schlomm T, Salomon G, Graefen M, et al.: Nerve distribution along the prostatic capsule. Eur Urol. 2007; 51: 105-10; discussion 110-1.

- Cathelineau X, Sanchez-Salas R, Barret E, Rozet F, Vallancien G: Is laparoscopy dying for radical prostatectomy? Curr Urol Rep. 2008; 9: 97-100.

- Hasan A, Pozzi M, Hamilton JR: New surgical procedures: can we minimise the learning curve? BMJ. 2000; 320: 171-3.

- Ahlering TE, Skarecky D, Lee D, Clayman RV: Successful transfer of open surgical skills to a laparoscopic environment using a robotic interface: initial experience with laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2003; 170: 1738-41.

- Samadi D, Levinson A, Hakimi A, Shabsigh R, Benson MC: From proficiency to expert, when does the learning curve for robotic-assisted prostatectomies plateau? The Columbia University experience. World J Urol. 2007; 25: 105-10.

- Rozet F, Jaffe J, Braud G, Harmon J, Cathelineau X, Barret E, Vallancien G: A direct comparison of robotic assisted versus pure laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: a single institution experience. J Urol. 2007; 178: 478-82.

- Vickers AJ, Bianco FJ, Serio AM, Eastham JA, Schrag D, Klein EA, et al.: The surgical learning curve for prostate cancer control after radical prostatectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007; 99: 1171-7.

- Ficarra V, Cavalleri S, Novara G, Aragona M, Artibani W: Evidence from robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: a systematic review. Eur Urol. 2007; 51: 45-55; discussion 56.

- Badani KK, Hemal AK, Peabody JO, Menon M: Robotic radical prostatectomy: the Vattikuti Urology Institute training experience. World J Urol. 2006; 24: 148-51.

- Tooher R, Swindle P, Woo H, Miller J, Maddern G: Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer: a systematic review of comparative studies. J Urol. 2006; 175: 2011-7.

- Klein EA, Bianco FJ, Serio AM, Eastham JA, Kattan MW, Pontes JE, et al.: Surgeon experience is strongly associated with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy for all preoperative risk categories. J Urol. 2008; 179: 2212-6; discussion 2216-7.

- Hu JC, Wang Q, Pashos CL, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL: Utilization and outcomes of minimally invasive radical prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2008; 26: 2278-84.

- Touijer K, Guillonneau B: Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: a critical analysis of surgical quality. Eur Urol. 2006; 49: 625-32.

- Stolzenburg JU, Rabenalt R, Do M, Schwalenberg T, Winkler M, Dietel A, et al.: Intrafascial nerve-sparing endoscopic extraperitoneal radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2008; 53: 931-40.

- Cathelineau X, Cahill D, Widmer H, Rozet F, Baumert H, Vallancien G: Transperitoneal or extraperitoneal approach for laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: a false debate over a real challenge. J Urol. 2004; 171: 714-6.

- Bishoff JT, Reyes A, Thompson IM, Harris MJ, St Clair SR, Gomella L, et al.: Pelvic lymphadenectomy can be omitted in selected patients with carcinoma of the prostate: development of a system of patient selection. Urology. 1995; 45: 270-4.

- Partin AW, Yoo J, Carter HB, Pearson JD, Chan DW, Epstein JI, et al.: The use of prostate specific antigen, clinical stage and Gleason score to predict pathological stage in men with localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 1993; 150: 110-4.

____________________

Accepted after revision:

September 26, 2009

_______________________

Correspondence address:

Dr. Xavier Cathelineau

Department of Urology

Institut Montsouris

42, Bd Jourdan, 75014

Paris, France

Fax: + 0033 1 5661 66 41

E-mail: xavier.cathelineau@imm.org

EDITORIAL COMMENT

Open radical

prostatectomy is the gold standard and most widespread treatment for clinically

localized prostate cancer. However, in recent years laparoscopic and robot-assisted

laparoscopic prostatectomy has rapidly been gaining acceptance among urologists

worldwide and has become an established treatment for organ-confined prostate

cancer.

Schuessler et al. in 1997 (1), described the initial experience in laparoscopic

radical prostatectomy (LRP), which they concluded that this technique

did not provide any advantages over open surgery.

As the authors described in this revision, in 1998, the Montsouris team

started their experience in LRP. LRP technique was well standardized and

changes have been gradually introduced as a natural evolution of the technique.

A better understanding of the periprostatic anatomy and further modification

of surgical technique will result in continued improvement in functional

outcomes and oncological control for patients undergoing radical prostatectomy,

whether by open or minimally-invasive surgery. The oncologic results are

in line with those reported with the use of the retropubic approach (2).

Today patients diagnosed with clinically localized prostate cancer have

more surgical treatment options than in the past including open, laparoscopic

and robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy.

However, cost-efficacy, learning curves and oncologic outcomes and remain

important considerations in the dissemination of minimally-invasive prostate

surgery.

REFERENCES

- Schuessler WW, Schulam PG, Clayman RV, Kavoussi LR: Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: initial short-term experience. Urology. 1997; 50: 854-7.

- Paul A, Ploussard G, Nicolaiew N, Xylinas E, Gillion N, de la Taille A, et al.: Oncologic Outcome after Extraperitoneal Laparoscopic Radical Prostatectomy: Midterm Follow-up of 1115 Procedures. Eur Urol. 2009; 17. [Epub ahead of print]

Dr. Mauricio Rubinstein

Section of Urology

Federal University of Rio de Janeiro State

Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

E-mail: mrubins74@hotmail.com