FOCAL

THERAPY WITH HIGH-INTENSITY FOCUSED ULTRASOUND FOR PROSTATE CANCER IN

THE ELDERLY. A FEASIBILITY STUDY WITH 10 YEARS FOLLOW-UP

(

Download pdf )

AMINE B. EL FEGOUN, ERIC BARRET, DOMINIQUE PRAPOTNICH, SHAWN SOON, XAVIER CATHELINEAU, FRANÇOIS ROZET, MARC GALIANO, RAFAEL SANCHEZ-SALAS, GUY VALLANCIEN

Department of Urology, Institute Montsouris, University Paris Descartes, Paris, France

Clinical Urology

Vol. 37 (2):

213-222, March - April, 2011

doi: 10.1590/S1677-55382011000200008

ABSTRACT

Purpose:

To evaluate the long-term efficacy of prostate cancer control and complication

rates, in the elderly, after focal therapy with high-intensity focused

ultrasound (HIFU).

Materials and Methods: Between June 1997

and March 2000, patients with localized prostate cancer were included

into a focal therapy protocol. Inclusion criteria were: PSA = 10 ng/mL,

= 3 positive biopsies with only 1 lobe involved, clinical stage = T2a,

Gleason score = 7 (3+4), negative CT scan and bone scan. Hemi-ablation

of the prostate was performed with the Ablatherm(R) device. Survival,

complication rates and urinary continence were evaluated. Control biopsies

were performed at 1 year. Treatment failure was defined as a positive

biopsy or need for salvage therapy.

Results: Twelve patients with a mean age

70 years were included. Median follow-up was 10 years. Control prostate

biopsies were negative in 11/12 (91%) patients. Overall survival was 83%

(10/12) and cancer specific survival was 100% at 10 years. Two patients

died from other causes. Recurrence free survival was 90% (95% CI; 0.71-1)

at 5 years, and 38% (95% CI; 0.04-0.73) at 10 years. Five patients had

salvage therapy with repeat HIFU (n = 1) or hormonal therapy (n = 4) and

all salvage patients were alive at 10 years. No patients developed lymph

node or bone metastasis. No patients suffered from urinary incontinence.

International Prostate Symptom Score was stable at 1 year. Complications

included two urinary tract infections and one episode of acute urinary

retention.

Conclusions: Hemi-prostate ablation with

HIFU can be safely performed in selected elderly patients with adequate

long-term cancer control and low complication rates. Results from larger

prospective studies using improved imaging techniques and extensive biopsy

protocols are awaited.

Key

words: prostate neoplasms; ultrasound; high-intensity focused;

transrectal

Int Braz J Urol. 2011; 37: 213-22

INTRODUCTION

Radical treatments such as radical prostatectomy (RP) or radiation therapy (RT) offer an excellent cancer cure rate around 85 to 90%, but post-treatment side-effects on urinary control and sexual function are common (1-3). In the elderly, the use of such radical treatments that reduce quality of life is questionable (3). Recently, there has been a demand to develop ablative therapies that attempt to reduce post-treatment side- effects, to avoid the psychological morbidity associated with active surveillance (AS) and maintain cancer control (4). In the United States, observational studies show that neither patients nor their physicians are enthusiastic about AS, an option chosen by only 10% of men (5). HIFU therapy, is a minimally invasive therapeutic option that has already shown efficacy in long-term cancer control with limited morbidity when applied to the whole gland (6,7). We hypothesize that applying HIFU on focal lesions could control disease with minimal harm to adjacent tissues, thus limiting post-treatment side effects of more radical therapy. We retrospectively reviewed our population and describe the long-term results of focal therapy with HIFU.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Between June 1997 and March 2000, patients with localized prostate cancer were included in a focal therapy protocol. Inclusion criteria were: prostate specific antigen (PSA) = 10 ng/mL, = 3 positive biopsies with only 1 lobe involved, clinical stage = T2a, Gleason score = 7 with no predominant pattern 4, and negative staging (absence of lymphadenopathy on CT scan and a negative bone scan). All patients provided written informed consent before entering the study. Patients with a previous history of any definitive treatment for prostate cancer or hormonal therapy were excluded.

Technique

Patients underwent HIFU with the first-generation Ablatherm(R) device (EDAP-TMS, Vaux-en-Velin France) using a 2.5 and 3 MHz transducer under general anesthesia. At the very beginning of our experience, even positive apical biopsies where considered suitable for HIFU treatment. Nevertheless, in the operative protocol, the sphincter was always avoided. Initially transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) was offered prior to HIFU in patients with large prostate volumes. It was subsequently done routinely since TURP reduces post-operative bladder outlet obstruction (8). Overall, 5 patients underwent TURP before HIFU.

Endpoints

Cancer

control: treatment failure was defined as any positive control biopsy

(irrespective of the side) and/or salvage therapy. Prostate biopsies were

performed at 1 year after treatment and if there was a rising PSA. Salvage

therapy was introduced on treatment failure, that is, when a control biopsy

was positive or when PSA increased to above pre-treatment levels. In case

of treatment failure, patients were offered HIFU if the recurrence was

considered local (one positive biopsy in the same lobe); if more diffuse,

they were offered androgen deprivation therapy. Adverse events, death

and cause of death were recorded. Overall survival was calculated at the

time of death, regardless of cause. Prostate cancer specific survival

was calculated at the time of death from prostate cancer.

Quality of Life

Treatment related morbidity was recorded. Continence was evaluated as the number of pads used per day at 1, 6 and 12 months. Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) were assessed with the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), before treatment, and at 1, 6, and 12 months. Sexual function was not assessed in this study because 7/12 patients were not interested in sexual activity or had pre-existing erectile dysfunction. The International Index of Erectile Function-5 questionnaires were unavailable for the remaining patients. Subjective information related to sexual function was available in the charts, but because of the lack of objective data, sexual function was not assessed in this analysis.

Follow-up

PSA measurements were performed in all patients at 3 months from initial HIFU treatment, and then every 6 months thereafter. Clinical assessment was performed every 6 months during the first 5 years and then annually thereafter. A six-core control biopsy involving both prostatic lobes was performed 1 year after treatment and/or in case of rising PSA. The data was analyzed retrospectively.

RESULTS

A total of 12 patients met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in this protocol. Pre-treatment patient characteristics are shown in Table-1. Long-term oncologic and functional outcomes are shown in Table-2. Data on patients with recurrence is shown in Table-3. The mean age was 70 years (± 4.8) and median procedure time was 69 minutes. Median number of shots was 374 (161-533), median catheterization time was 2.5 days (range, 2-13). Mean prostate volume was 37 g (23-62), mean pre-operative PSA level was 7.3 ng/mL (2.6-10), mean number of positive biopsies was 2 (1-3) and median follow-up was 10.6 years (7.5-11.1). Six of the twelve patients had an initial apical positive biopsy. For two of these patients, this biopsy was the only positive biopsy. Control biopsies at one year were negative in 11/12 patients (91%). One of twelve patients harbored a residual Gleason 4 (2+2) cancer. This one patient with low grade, low volume disease was monitored with serial PSA, and was treated 4 years later with a second HIFU procedure on PSA increase. Treatment failure was observed in 5 patients. These patients had a salvage therapy with either HIFU (n = 1) or androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) (n = 4) and survival rate for recurrent patients was 100% at 9.5 to 11 years of follow-up. Three of the six patients with an initial apical positive biopsy recurred. None of the recurrences had subsequent lymphadenopathy or bone metastasis on staging. The last median PSA in the recurrence-free group was 1.63 ng/mL (range, 0.42-6.82). The patient re-treated with HIFU had a stable PSA at 4.6 ng/mL, 4.5 years after salvage HIFU treatment alone. The group treated with salvage ADT has a stable median PSA at 1.15 ng/mL (range, 0.13-3.2).

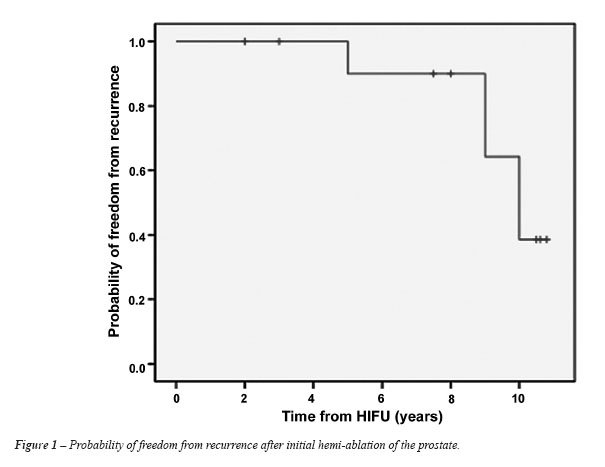

Two patients died during the follow-up period

from non-cancer related causes (both from heart failure), they were free

of disease when they died 2 and 3 years, respectively, with a PSA at 1.18

ng/mL and 0.42 ng/mL on the last follow-up. Each also had a negative control

biopsy. Recurrence free survival was 90% (95% CI; 0.71-1) at 5 years,

and 38% (95% CI; 0.04-0.73) at 10 years (Figure-1). Overall survival was

83% (10/12 still alive) and cancer specific survival was 100%. No urinary

incontinence was observed. Two of twelve patients experienced urinary

tract infection post-operatively: one episode of epididimo-orchitis, and

one asymptomatic urinary tract infection. One patient experienced acute

urinary retention post-operatively and had a supra-pubic catheter placed

for 13 days. No urethral strictures were recorded. One patient did not

have an IPSS score recorded. Eight of eleven patients (75%) had a similar

IPSS 1 year after treatment. Two of eleven patients had a lower IPSS and

one of eleven patients had a higher IPSS. Of the two patients with lower

IPSS scores one year after HIFU treatment; one did not receive further

therapy for lower urinary tract symptoms, while the other patient underwent

a TURP before HIFU to prevent post-treatment urinary retention.

COMMENTS

In

the PSA era, low-risk disease represents a growing proportion of newly

diagnosed prostate cancer. Recent data from Cancer of the Prostate Strategic

Urological Research Endeavor demonstrates the number of patients with

low-risk tumor characteristics (defined as serum PSA = 10 ng/mL, Gleason

score = 6 and clinical stage = T2a) rose from 27.5% from 1990 to 1994,

to 46.4% from 2000 to 2001 (5). Focal therapy has been suggested as an

alternative to radical treatment (4).

In our study, focal therapy with HIFU provided a 5 and 10 years recurrence

free survival of 90% and 38%, an overall survival of 83% (10/12), and

a cancer specific survival of 100% (12/12). Besides

the very large 95% CI resulting from the small sample size, these results

are comparable to HIFU treatment of the whole gland. In a multicenter

analysis including 140 patients treated with HIFU for the whole gland

(7), the overall survival was 90% at 5 years and 83% at 8 years. Prostate

cancer specific-survival rate was 98%. Treatment failure was defined as

presence of at least one positive biopsy, PSA > nadir PSA + 2 ng/mL

or salvage therapy. In this analysis, disease free survival was 66% at

5 years, and 59% at 7 years. When stratified for risk-group, disease free

survival at 5 years was 68% for low risk patients and 58% for the intermediate

risk patients (p = 0.021).

General limitations of whole-gland HIFU

also apply to focal therapy. The major limitation is apical cancer. In

the beginning of our experience, apical cancers were considered suitable

for HIFU and six of twelve patients had apical cancers in this study,

including 2 patients with exclusively apical lesions. Half of these patients

recurred in our series (2 patients in both lobes and 1 patient at the

apex). Increased incontinence risk has been described with treating apical

lesions (9). Even at the beginning of our experience special attention

was given to the sphincter and no urinary incontinence was observed in

this study. Improvement in real-time magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

thermometry for monitoring the treatment effect can further reduce the

risk of treating apical lesions (10). Re-treatment with HIFU is also a

relatively safe option since there is no cumulative effect of ultrasound.

In a cohort of 223 patients with a retreatment rate of 22%, Blana et al.

reported there was no significant difference in urinary infection, outlet

obstruction, and chronic pelvic pain after one or several HIFU sessions.

However, they observed a significant increase in urinary incontinence

and impotence rates in this retreatment group (11). Salvage radiotherapy

(RT) has recently been described as an option after HIFU failure with

reasonable results (12). Even if most of our patients were treated with

ADT, focal therapy with HIFU allows many options for salvage therapy such

as repeat HIFU (9,11,13), RT (12), and radical prostatectomy (RP) (14)

in case of recurrence.

Although radical treatment offers excellent

cancer cure rates, post treatment side effects on urinary, sexual and

bowel function are common (15). In the low-risk patient, RP offers a probability

of freedom from progression of 79% to 91% and a cancer specific survival

rate of 97% and 89% at 10 and 15 years (1,2). RT provides a 10-year progression-free

survival rate for low risk patients treated with 75.6 Gy of 85% (16).

For RP, urinary incontinence and impaired sexual function rates were 14%

and 79%, respectively, 5 years after treatment. For RT, these values were

4% and 64%, respectively, 5 years after treatment (17). Gastrointestinal

problems occur in 59% of patients undergoing RT compared to 14% of age-matched

controls (18). Compared with radical treatment, focal therapy could provide

a way to control low-risk cancers with minimal morbidity. In our population,

the only side-effects were urinary tract infection in 2 cases and acute

urinary retention in 1 case. With the routine use of pre-operative TURP,

the rate of urinary retention can be reduced (8). Nevertheless, we do

not perform pre-HIFU TURPs for our focal therapy patients, since this

is not in agreement with our definition of focal therapy. Furthermore,

LUTS were not significantly changed by HIFU 12 months after treatment

and no urethral strictures were recorded. As expected, our data demonstrates

focal therapy with HIFU minimizes side-effects. Our findings are also

better than the results for the whole gland HIFU protocols reported in

the literature. In a multicenter trial conducted on 402 patients, urinary

retention was present in 9% of patients, urethral strictures developed

in 4%, and epididymitis in 6% (9). In another study 94% of patients recovered

normal urinary continence, 14% had urinary obstruction associated with

strictures, 6% complained of pelvic pain for less than 6 months and 26%

previously potent patients developed severe erectile dysfunction (7).

In a phase II trial assessing feasibility, safety and early efficacy of

hemi prostate ablation with HIFU, Emberton et al. found that the probability

of men being free of significant genito-urinary toxicity was 95% at 3

months. Patients were 100% pad-free immediately following treatment. Erectile

function sufficient for intercourse occurred in 70% by 2 weeks, and at

3 months, 95% had erections sufficient for penetration (19). In a prospective

study, comparing whole gland and focal therapy with HIFU, these two options

where equivalent for short-term cancer control. No signi?cant differences

were observed in the 2 year biochemical disease free survival for patients

in the low and intermediate risk groups. Complications tended to be lower

in the focal therapy group (20).

Despite reasonable short-term evidence supporting

the safety and feasibility of AS in men with low-risk prostate cancer

(21), few patients accept this approach. Active surveillance among patients

older than 75 years has fallen by half in the PSA era, with less than

one-quarter of low-risk patients electing initial observation (22). Moreover,

due to anxiety, 50% of these patients usually exit the surveillance protocols

during follow-up (21). Compared with AS, focal therapy offers a method

to treat the index foci of cancer, relieving anxiety associated with waiting

for the disease to progress. Focal HIFU is an attractive option with the

advantage of delaying definitive therapy and minimizing its associated

adverse effects on patients’ quality of life (23).

Despite obvious limitations of a non-randomized

retrospective study, including a small sample size, our results are interesting

with regards to the long-term oncologic and functional outcomes after

hemi-ablation of the prostate with HIFU. One of the weaknesses of our

study is the use of a sextant biopsy protocol as recommended in the 1990’s.

Standard transrectal prostate biopsy strategies have been developed to

improve cancer detection but not to accurately locate or stage prostate

tumors. To better characterize cancer location, many different techniques

such as image guidance with color Doppler ultrasonography or MRI, transrectal

saturation biopsies and perineal mapping biopsies are under evaluation

(24-27). Sextant biopsy protocols are insufficient to correctly characterize

the cancer and some tumors may have been underestimated (28). It is not

clear to what extent this under sampling can explain the recurrence rate

observed in our study. One can argue that prostate cancer multifocality

explains the high level of recurrence when the whole gland is not treated,

and that focal therapy may be of limited efficacy. More than 80% of the

patients have multifocal prostate cancer (29) with 80% of secondary tumor

foci < 0.5 cm3 (30). Volume distribution of the secondary cancers,

however, is almost identical to the cancers found incidentally in men

undergoing cystoprostatectomy for bladder cancer (29). There is a growing

body of evidence to support that the prognosis of the disease is driven

by the index tumor foci. Our results are concordant with this assertion

and it is encouraging to observe that the 10 year cancer specific and

disease free survival of this small sample feasibility study are comparable

to the whole gland treatment with HIFU.

Prostate cancer treatments have dramatically

evolved towards a more selective approach in order to reduce treatment

burden whilst retaining cancer control. Over 10 years ago, our team has

embraced HIFU for the treatment of prostate cancer and for the first time

we have described the long-term efficacy of focal therapy with HIFU and

the limited morbidity of this procedure. Our results are encouraging and

we plan to include more patients and eventually younger patients with

very strict selection criteria. The main limitation of this non-randomized

retrospective study is the small sample size, which precludes statistical

analysis; thus, our findings must be interpreted according to this limitation.

The ongoing evolution of imaging is also an exciting and important variable

in the development of focal therapy (31). As previously defined for open

radical prostatectomy, the trifecta remains the essential group of variables

to evaluate for any focal therapy approach (1,32). At the beginning of

the HIFU experience, we neither had a definition of risk of recurrence,

nor a definition for focal therapy. The definition of focal therapy for

prostate cancer describes the treatment of men with organ-confined, low

to moderate risk prostate cancer. In these cases, the patient undergoes

ablation of only the malignant tumor foci in order to provide acceptable

freedom from disease progression and also a high probability of preserving

genitourinary and bowel function.

According to the literature, HIFU is a treatment

of proven efficacy for localized prostate cancer with limited side-effects.

It offers the opportunity to treat elderly patients with a minimally invasive

technique that can be repeated and in our initial series could be combined

with TURP to offer better urinary outcome (33-36).

A focal approach for prostate cancer performed

ten years ago and based on a sextant biopsy diagnosis allowed patients

to have similar outcomes as patients treated in the same period with a

whole gland approach. This cohort should further expand the discussion

on focal therapy, because selected elderly patients were offered ablation

of only a half of their prostates and were conferred an acceptable freedom

from disease progression and cancer-specific survival.

CONCLUSIONS

This retrospective feasibility study shows that hemi-prostate ablation with HIFU is a reasonable treatment strategy for a selected population of low or intermediate risk prostate cancer in elderly men. The long-term cancer control rate is adequate, recurrences can be treated with a second HIFU session or other techniques. In the elderly, the concept of cancer control instead of cancer cure with HIFU has to be discussed, as it seems to provide an effective long-term disease control with minimal treatment-related morbidity. More extensive biopsy protocols and more accurate imaging techniques will certainly improve patients’ selection. Larger prospective studies with a long follow-up are awaited to confirm our small size preliminary results.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Bianco FJ Jr, Scardino PT, Eastham JA: Radical prostatectomy: long-term cancer control and recovery of sexual and urinary function (“trifecta”). Urology. 2005; 66(5 Suppl): 83-94.

- Roehl KA, Han M, Ramos CG, Antenor JA, Catalona WJ: Cancer progression and survival rates following anatomical radical retropubic prostatectomy in 3,478 consecutive patients: long-term results. J Urol. 2004; 172: 910-4.

- Alibhai SM, Naglie G, Nam R, Trachtenberg J, Krahn MD: Do older men benefit from curative therapy of localized prostate cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2003; 21: 3318-27.

- Scardino PT, Abenhaim LL: Focal therapy for prostate cancer: analysis by an international panel. Urology. 2008; 72(6 Suppl): S1-2.

- Cooperberg MR, Broering JM, Kantoff PW, Carroll PR: Contemporary trends in low risk prostate cancer: risk assessment and treatment. J Urol. 2007; 178: S14-9.

- Gelet A, Chapelon JY, Bouvier R, Souchon R, Pangaud C, Abdelrahim AF, et al.: Treatment of prostate cancer with transrectal focused ultrasound: early clinical experience. Eur Urol. 1996; 29: 174-83.

- Blana A, Murat FJ, Walter B, Thuroff S, Wieland WF, Chaussy C, et al.: First analysis of the long-term results with transrectal HIFU in patients with localised prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2008; 53: 1194-201.

- Vallancien G, Prapotnich D, Cathelineau X, Baumert H, Rozet F: Transrectal focused ultrasound combined with transurethral resection of the prostate for the treatment of localized prostate cancer: feasibility study. J Urol. 2004; 171: 2265-7.

- Thüroff S, Chaussy C, Vallancien G, Wieland W, Kiel HJ, Le Duc A, et al.: High-intensity focused ultrasound and localized prostate cancer: efficacy results from the European multicentric study. J Endourol. 2003; 17: 673-7.

- de Senneville BD, Mougenot C, Moonen CT: Real-time adaptive methods for treatment of mobile organs by MRI-controlled high-intensity focused ultrasound. Magn Reson Med. 2007; 57: 319-30.

- Blana A, Rogenhofer S, Ganzer R, Wild PJ, Wieland WF, Walter B: Morbidity associated with repeated transrectal high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment of localized prostate cancer. World J Urol. 2006; 24: 585-90.

- Pasticier G, Chapet O, Badet L, Ardiet JM, Poissonnier L, Murat FJ, et al.: Salvage radiotherapy after high-intensity focused ultrasound for localized prostate cancer: early clinical results. Urology. 2008; 72: 1305-9.

- Poissonnier L, Chapelon JY, Rouvière O, Curiel L, Bouvier R, Martin X, et al.: Control of prostate cancer by transrectal HIFU in 227 patients. Eur Urol. 2007; 51: 381-7.

- Liatsikos E, Bynens B, Rabenalt R, Kallidonis P, Do M, Stolzenburg JU: Treatment of patients after failed high intensity focused ultrasound and radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: salvage laparoscopic extraperitoneal radical prostatectomy. J Endourol. 2008; 22: 2295-8.

- Korfage IJ, Essink-Bot ML, Borsboom GJ, Madalinska JB, Kirkels WJ, Habbema JD, et al.: Five-year follow-up of health-related quality of life after primary treatment of localized prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 2005; 116: 291-6.

- Dearnaley DP, Sydes MR, Graham JD, Aird EG, Bottomley D, Cowan RA, et al.: Escalated-dose versus standard-dose conformal radiotherapy in prostate cancer: first results from the MRC RT01 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007; 8: 475-87.

- Potosky AL, Davis WW, Hoffman RM, Stanford JL, Stephenson RA, Penson DF, et al.: Five-year outcomes after prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004; 96: 1358-67.

- Widmark A, Fransson P, Tavelin B: Self-assessment questionnaire for evaluating urinary and intestinal late side effects after pelvic radiotherapy in patients with prostate cancer compared with an age-matched control population. Cancer. 1994; 74: 2520-32.

- Ahmed HU, Zacharakis E, Dudderidge T, Armitage JN, Scott R, Calleary J, et al.: High-intensity-focused ultrasound in the treatment of primary prostate cancer: the first UK series. Br J Cancer. 2009; 101: 19-26.

- Muto S, Yoshii T, Saito K, Kamiyama Y, Ide H, Horie S: Focal therapy with high-intensity-focused ultrasound in the treatment of localized prostate cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008; 38: 192-9.

- Klotz L: Active surveillance with selective delayed intervention: using natural history to guide treatment in good risk prostate cancer. J Urol. 2004; 172: S48-50; discussion S50-1.

- Cooperberg MR, Lubeck DP, Meng MV, Mehta SS, Carroll PR: The changing face of low-risk prostate cancer: trends in clinical presentation and primary management. J Clin Oncol. 2004; 22: 2141-9.

- Eggener SE, Scardino PT, Carroll PR, Zelefsky MJ, Sartor O, Hricak H, et al.: Focal therapy for localized prostate cancer: a critical appraisal of rationale and modalities. J Urol. 2007; 178: 2260-7.

- Pelzer A, Bektic J, Berger AP, Pallwein L, Halpern EJ, Horninger W, et al.: Prostate cancer detection in men with prostate specific antigen 4 to 10 ng/mL using a combined approach of contrast enhanced color Doppler targeted and systematic biopsy. J Urol. 2005; 173: 1926-9.

- Puech P, Huglo D, Petyt G, Lemaitre L, Villers A: Imaging of organ-confined prostate cancer: functional ultrasound, MRI and PET/computed tomography. Curr Opin Urol. 2009; 19: 168-76.

- Chon CH, Lai FC, McNeal JE, Presti JC Jr: Use of extended systematic sampling in patients with a prior negative prostate needle biopsy. J Urol. 2002; 167: 2457-60.

- Moran BJ, Braccioforte MH, Conterato DJ: Re-biopsy of the prostate using a stereotactic transperineal technique. J Urol. 2006; 176: 1376-81; discussion 1381.

- Tareen B, Godoy G, Sankin A, Temkin S, Lepor H, Taneja SS: Can contemporary transrectal prostate biopsy accurately select candidates for hemi-ablative focal therapy of prostate cancer? BJU Int. 2009; 104: 195-9.

- Wise AM, Stamey TA, McNeal JE, Clayton JL: Morphologic and clinical significance of multifocal prostate cancers in radical prostatectomy specimens. Urology. 2002; 60: 264-9.

- Villers A, McNeal JE, Freiha FS, Stamey TA: Multiple cancers in the prostate. Morphologic features of clinically recognized versus incidental tumors. Cancer. 1992; 70: 2313-8.

- Prando A: Clinical stage T1c prostate cancer: evaluation with endorectal MR imaging and MR spectroscopic imaging. Int Braz J Urol. 2010; 36: 100-1.

- DiBlasio CJ, Derweesh IH, Malcolm JB, Maddox MM, Aleman MA, Wake RW: Contemporary analysis of erectile, voiding, and oncologic outcomes following primary targeted cryoablation of the prostate for clinically localized prostate cancer. Int Braz J Urol. 2008; 34: 443-50.

- Barua J, Campbell I I, Cole O, Harris D, Kaisary A, Larner T, et al.: High-intensity focused ultrasound for localized prostate cancer: initial experience with a 2-year follow-up. BJU Int. 2009; 104: 1794; authors reply 1794-5.

- Abdel-Wahab M, Pollack A: Prostate cancer: Defining biochemical failure in patients treated with HIFU. Nat Rev Urol. 2010; 7: 186-7.

- Berge V, Baco E, Karlsen SJ: A prospective study of salvage high-intensity focused ultrasound for locally radiorecurrent prostate cancer: Early results. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2010; 44: 223-7.

- Uchida T, Shoji S, Nakano M, Hongo S, Nitta M, Murota A, et al.: Transrectal high-intensity focused ultrasound for the treatment of localized prostate cancer: eight-year experience. Int J Urol. 2009; 16: 881-6.

____________________

Accepted

after revision:

July 30, 2010

_______________________

Correspondence

address:

Dr. Eric Barret

Department of Urology

Institut Montsouris,

42, boulevard Jourdan,

75014, Paris, France

Fax: + 33 1 5661-6641

E-mail:eric.barret@imm.fr

EDITORIAL COMMENT

During

the last decade developments showed that in most oncologic therapies invasiveness

has been reduced. Instead of removing the entire organ radically and surgically

the focus is now on the treatment of cancer affected areas only.

Focal therapy in prostate cancer had first

been introduced for “male lumpectomy” in 2004 by G. Onic using

Cryotherapy.

Statistics show that all local therapies

have a high cancer-specific long-term survival rate.

Therefore, the time seems to be right for

“NOTES” (Natural Orifice Therapeutic Endoscopic Surgery) -

as it is provided by HIFU (High Intensity Focused Ultrasound).

The Montsouris group has used transrectal

pulsed focused HIFU since 1996 when it was introduced into clinical practice.

They participated in multicenter studies and registered their data in

a database ready to be stratified according to specific patient or indication

groups. In past years “focal” HIFU has been restricted to

few specific cases based on individual medical decision. Thirteen patients

have been treated based on current focal HIFU criteria in 12 years (unilateral,

low risk PCa treated by hemi-ablation only). Their results have been collected

and retrospectively analyzed. The data underline the feasibility of the

focal HIFU concept as a realistic balance between low invasiveness, sufficient

radicality and low side-effect rate. Even though recurrence free survival

of 90% after 5 years decreased to 38% after 10 years, cancer-specific

survival still remained 100%.

However, it proves, that this collection

of individual indications confirms the feasibility of the focal concept

and the validity of “focal HIFU therapy” as well as the rationality

of using the NOTES approach for this indication.

It is not possible to draw more statements

from a study with such a small number of patients treated by different

devices, with different technical settings and a changing application

mode.

Other minimal invasive therapies such as

Brachy-, Cryo- or Photodynamic therapy are technically able to perform

partial treatments as well, but the disadvantage of perineal, tissue and

cancer perforating approaches cannot compete with the non invasive NOTES

approach by transrectal HIFU.

Patients who decide for focal therapy want

to avoid side-effects without major loss of cancer treatment efficacy.

Even though this publication is just a feasibility study with 13 patients

it proves that this desire of the patient can be met by the focal treatment

of PCa with High Intensity Focused Ultrasound.

Focal HIFU may be the first step to postpone

more invasive therapies, to preserve functional and sexual prostatic integrity

without the psychological burden of “watchful waiting” in

prostate cancer therapy.

Once better diagnostic technologies visualize

PCa affected areas, focal HIFU with its NOTES approach will have an even

higher acceptance within the urological armentarium to treat prostate

cancer.

Dr. Christian

Chaussy &

Dr. Stefan Thueroff

Department of Urology

Klinikum Munich-Harlaching

Sanatoriumsplatz 2

D-81545, Muenchen, Germany

E-mail: chau1@aol.com