RADIOLOGICAL

CLASSIFICATION OF RENAL ANGIOMYOLIPOMAS BASED ON 127 TUMORS

(

Download pdf )

ADILSON PRANDO

Department of Radiology, Vera Cruz Hospital, Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Purpose:

Demonstrate radiological findings of 127 angiomyolipomas (AMLs) and propose

a classification based on the radiological evidence of fat.

Materials and Methods: The imaging findings

of 85 consecutive patients with AMLs: isolated (n = 73), multiple without

tuberous sclerosis (TS) (n = 4) and multiple with TS (n = 8), were retrospectively

reviewed. Eighteen AMLs (14%) presented with hemorrhage. All patients

were submitted to a dedicated helical CT or magnetic resonance studies.

All hemorrhagic and non-hemorrhagic lesions were grouped together since

our objective was to analyze the presence of detectable fat. Out of 85

patients, 53 were monitored and 32 were treated surgically due to large

perirenal component (n = 13), hemorrhage (n = 11) and impossibility of

an adequate preoperative characterization (n = 8). There was not a case

of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) with fat component in this group of patients.

Results: Based on the presence and amount

of detectable fat within the lesion, AMLs were classified in 4 distinct

radiological patterns: Pattern-I, predominantly fatty (usually less than

2 cm in diameter and intrarenal): 54%; Pattern-II, partially fatty (intrarenal

or exophytic): 29%; Pattern-III, minimally fatty (most exophytic and perirenal):

11%; and Pattern-IV, without fat (most exophytic and perirenal): 6%.

Conclusions: This proposed classification

might be useful to understand the imaging manifestations of AMLs, their

differential diagnosis and determine when further radiological evaluation

would be necessary. Small (< 1.5 cm), pattern-I AMLs tend to be intra-renal,

homogeneous and predominantly fatty. As they grow they tend to be partially

or completely exophytic and heterogeneous (patterns II and III). The rare

pattern-IV AMLs, however, can be small or large, intra-renal or exophytic

but are always homogeneous and hyperdense mass. Since no renal cell carcinoma

was found in our series, from an evidence-based practice, all renal mass

with detectable fat should be considered an AML.

Key

words: kidney neoplasms; angiomyolipomas; diagnostic imaging;

tomography, X-ray computed; hemorrhage

Int Braz J Urol. 2003; 29: 208-16

INTRODUCTION

Renal angiomyolipomas (AMLs) are benign neoplasms composed of mature adipose tissue, thick-walled blood vessels, and smooth muscle in varying proportions (1). Definite diagnosis of AML on computed tomography (CT) studies is made when macroscopic fat (low-density areas of -30 to -100 HU) is identified within the lesion (2,3). Our purpose is to demonstrate the imaging findings of 127 AMLs and to propose a radiological classification based on the presence and amounts of detectable fat.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between March 1995 and December 2001, renal AML was diagnosed in 85 consecutive patients at our institution. We retrospectively reviewed the imaging findings of these patients with AMLs (isolated, n = 73), multiple with tuberous sclerosis - TS (n = 8) and multiple without TS (n = 4). The patients were aged from 17 to 68 years (mean = 32 years). All patients had previous ultrasound (US) and were submitted to a dedicated helical CT. Non-contrast scans using 10-mm sections was initially done. If fat was not seen, 3- to 5-mm wide sections were scanned. In lesions smaller than 2 cm, 1 or 3-mm CT sections were performed and measurement of the attenuation values of individual pixels, were obtained (4). If fat was identified (more than 3 contiguous pixel with values below -30 HU), no further work-up was done. If no fat was seen, the patient received intravenous contrast injection for adequate preoperative staging since the mass was considered a renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Magnetic resonance was done as an additional method of evaluation in 16 patients. Of the 85 patients, 53 were followed by US or CT for 1 to 3 years to confirm stability, 32 were treated surgically due to a large perirenal component (n = 15), hemorrhage (n = 13) and impossibility of an adequate preoperative characterization (n = 4).

RESULTS

Tumor

size ranged from 0.5 to 36.5 cm in diameter. Follow-up studies demonstrated

growing of the AMLs in 2 patients with multiple lesions. Eighteen AMLs

(14%) were hemorrhagic, including 11 associated with spontaneous renal

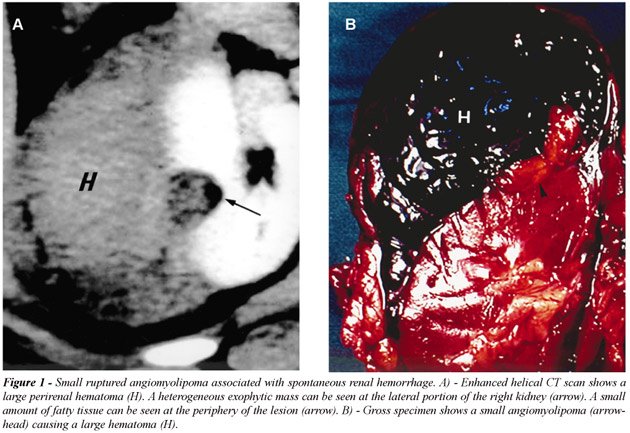

bleeding. Three of these lesions measured 2 to 4 cm in diameter (Figure-1).

The presence of an intrarenal or perinephric hematoma almost obscured

the fatty component of the tumor in the majority of patients. All hemorrhagic

and non-hemorrhagic lesions were grouped together since our objective

was to analyze the presence and the amounts of detectable fat. Based on

this criterion, AMLs were classified into 4 distinct radiological patterns:

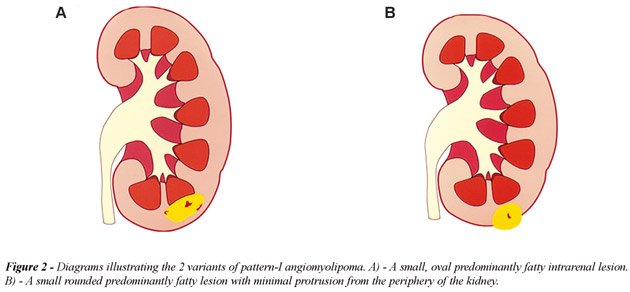

a) Pattern-I AML, predominantly fatty, included 68 lesions (54%): in this

group, the AMLs measured 0.5 to 3 cm in diameter and were oval or round

in shape, predominantly intrarenal or with discrete protrusion outside

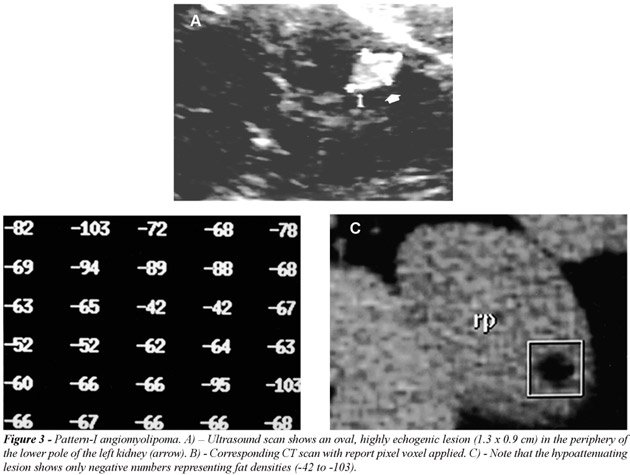

the kidney (Figure-2). All oval, or less frequently round, highly echogenic

lesions smaller than 1.5 cm on ultrasound were proved to be an AML by

helical-CT (Figure-3). Three of 16 lesions larger than 2 cm occurred in

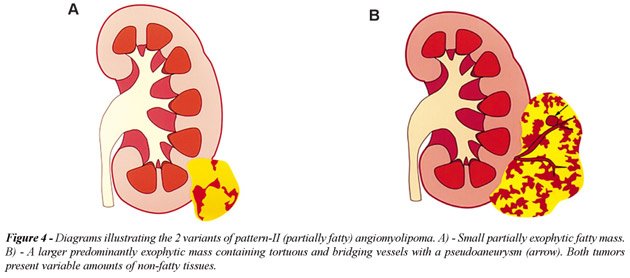

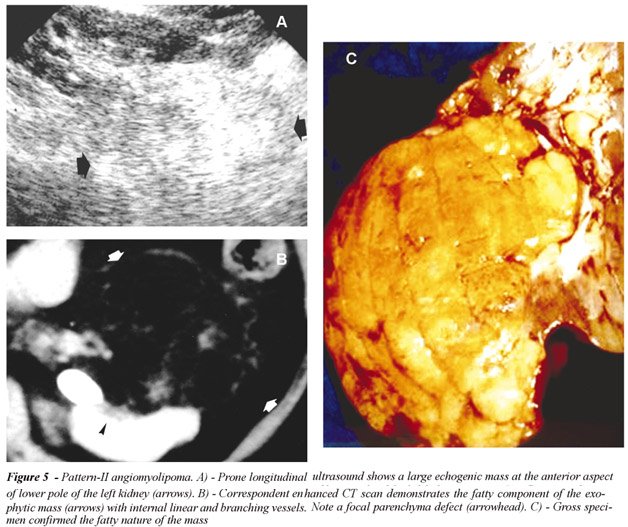

the renal sinus; b) Pattern-II AML, partially fatty, included 36 lesions

(29%): this group consisted of 22 small (3 to 5 cm) and 14 large (>5

to 36.5 cm) partially or predominantly exophytic masses extending outside

the kidney into the retroperitoneal space (Figure-4). These lesions presented

with variable amounts of non-fatty soft tissue mass, intratumoral vessels

or internal or perinephric hematoma (Figure-5). Only 2 AMLs were completely

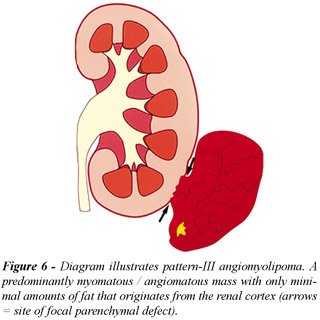

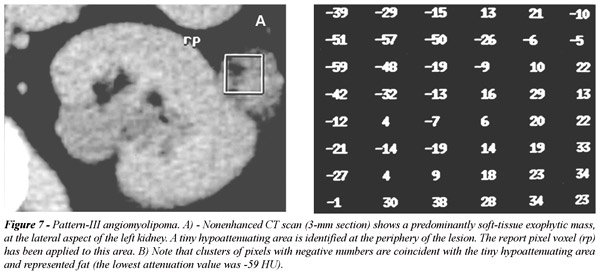

intrarenal and other 2 manifested as a renal sinus tumor; c) Pattern-III

AML, minimally fatty, included 8 lesions (11%): most AMLs with minimal

fat content manifested as a tumor with a predominantly extrarenal growth

extending into the perirenal space (Figure-6). The report pixels method

was essential for the detection of tiny amounts of fat within these lesions

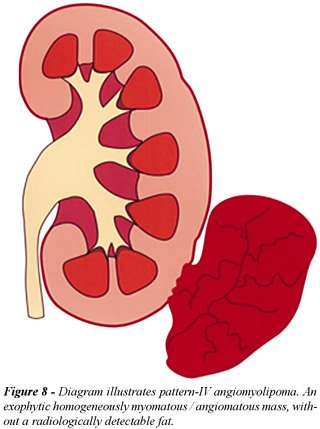

(Figure-7); d) Pattern-IV AML, without detectable fat, included 4 lesions

(6%): all 4 masses were predominantly exophytic and occurred only in non-TS

patients (Figure-8). All lesions showed high homogeneous attenuation on

nonenhanced CT scans and homogeneous enhancement on contrast-enhanced

CT images (11). In large lesions the presence of a small parenchyma defect

was important to determine its renal origin. All tumors were surgically

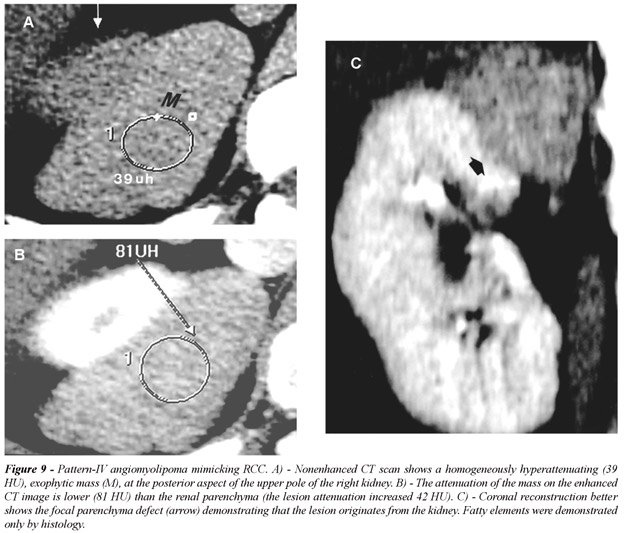

removed due to the preoperative diagnosis of a RCC (Figure-9).

DISCUSSION

Renal AML is a fairly common lesion, often discovered incidentally during ultrasound examination in women (30 - 60 years of age) and appears as hyperechoic mass with echogenicity similar or less intense than the renal sinus fat. They are usually single and small lesions, measuring 0.5 to 3 cm. About 20% of patients with AMLs have tuberous sclerosis (TS). In this condition, these tumors tend to be multiple and bilateral and have no gender predilection. Flank pain, hematuria or palpable mass, may result from its bleeding or large size. Small AMLs are usually further investigated with CT in order to differentiate from small hyperechoic renal cell carcinomas while larger AML may mimic perirenal liposarcomas. For these reasons and the fact that there are still controversies regarding the incidence of AMLs without fat, we propose an original radiological classification of these tumors. The purpose of this classification, which is based on the presence and amounts of detectable fat, is to demonstrate that variable radiological manifestations of AMLs are related to their growing mechanism. This knowledge may facilitate their differential diagnosis and their radiological work-up. In our series of 127 lesions, all tumors with detectable fat by dedicated helical-CT study, even those were fat was obscured by hematoma, proved to be an AML (n = 123, 94%). Pattern-I, the most common manifestation of AML, can be differentiated from hyperechoic small RCC when a hypoechoic rim (pseudocapsule) or intratumoral tiny cysts are identified (5-7). When small pattern-I lesions (< 1.5 cm), are detected by ultrasound, no further investigation with CT is necessary since in our series all of these lesions proved to be AMLs. Spontaneous renal bleeding secondary to an AML usually occurs when the tumor is larger than 4 cm (8), but in 3 of 11 lesions (27%), the tumor measured 2.5 to 4 cm in diameter. Spontaneously hemorrhagic pattern-II renal AMLs must be differentiated from a RCC or other vascular entities (9). For this reason a careful search must be done during CT evaluation in order to detect fat (3), which in our series was invariable found at the periphery of the lesion (Figure-2). As this tumor grows they tend to be exophytic (pattern II or III). These lesions should be distinguished from well-differentiated, low grade retroperitoneal or capsular liposarcoma and the very rare RCC engulfing perirenal fat (10,11). AML can be distinguished from a perirenal liposarcoma on CT scans by the presence of typical internal tortuous angiomatous vessels and a renal parenchyma defect (Figure-5); both findings usually not seen in liposarcomas (10). Pattern-IV AML has a distinct radiological behavior; as they grow the lesions maintain its high attenuation, homogeneous enhancement and its exophytic appearance (12). Similarly to pattern-III AML, the demonstration of a renal parenchyma defect in pattern IV AML is essential in order to establish its origin. Although isolated cases of calcified and non-calcified RCC containing fat has been described (13,14), for an evidence-based practice, all renal mass with detectable fat should be considered an AML.

CONCLUSIONS

This proposed classification might be useful to understand the imaging manifestations of AMLs, their differential diagnosis and the necessity for eventual further radiological work-up. Small (< 1.5 cm), pattern-I AMLs tend to be homogeneous predominantly intra-renal, fatty lesion. In our series, all hyperechoic lesions measuring 1.5 cm or less represented an AML; therefore, further evaluation with helical CT is probably not necessary in this group of patients. As these lesions grow they tend to present variable amounts of non-fatty tissue and vascular components and to appear as partially or completely exophytic and heterogeneous (patterns II and III). Pattern-IV AMLs, however, although extremely rare (only 6%) can be small or large, but are always exophytic homogeneous and hyperdense renal mass. Although pattern-IV AML present some suggestive radiological signs, differentiation from malignant renal tumor is almost impossible. Since no renal cell carcinoma was found in our series, from an evidence-based practice, all renal mass with detectable fat should be considered an AML.

REFERENCES

- Bennington JL, Beckwith JB: Tumors of the Kidney, Renal Pelvis, and Ureter. In: Firminger HI (ed). Atlas of Tumor Pathology. 2nd ed. Washington, AFIP. 1975; Series 2, fasc 12.

- Bosniak MA: AML of the kidney: a prospective diagnosis is possible in virtually every case. Urol Radiol. 1981; 3: 135-42.

- Bosniak MA, Megibow AJ, Hulnick D, Horii S, Raghavendra BN: CT diagnosis of renal AML: the importance of detecting small amounts of fat. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988; 151:497-501.

- Kurosaki Y, Tanaka Y, Kuramoto K, Itay Y: Improved CT fat detection in small kidney AMLs using thin sections and single voxel measurements. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1993; 17:745-8.

- Forman HP, Middleton WE, Nelson GL, McClennan BL: Hyperechoic RCC: increase in detection at US. Radiology 1993; 188: 431-4.

- Siegel CL, Middleton WD, Teefey SA, McClennan B: Hyperechoic renal tumors: anechoic rim and intratumoral cysts in US differentiation of RCC from AML. Radiology 1996; 198: 789-93.

- Silverman SG, Pearson GD, Seltzer SE, Polger M, Tempany CM, Adams DF, et al: Small (< 3 cm) hyperechoic renal masses: comparison of helical an conventional CT for diagnosis AML. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996; 167: 877-81.

- Oesterling JE, Fishman EK, Goldman SM: The management of renal AML. J Urol. 1986; 135: 1121-4.

- Zhang LQ, Fielding JR, Zou KH: Etiology of spontaneous perirenal hemorrhage: a meta-analysis. J Urol. 2002; 167: 1593-6.

- Israel GM, Bosniak MA, Slywotzky CM, Rosen RJ: CT differentiation of large exophytic renal AMLs and perirenal liposarcomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002; 179: 769-73.

- Prando A: Intratumoral fat in a renal cell carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991; 156: 871.

- Jinzaki M, Tanimoto A, Narimatsu Y: AML: imaging findings in lesion with minimal fat. Radiology. 1997; 2002: 497-502.

- Helenon O, Merrian S, Paraf F: Unusual fat-containing tumors of the kidney: a diagnostic dilemma. Radiographics 1997; 17: 129-44.

- D’Angelo PC, Gash JR, Hoin AW, Klein FA: Fat in renal cell carcinoma that lacks associated calcifications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002; 178: 931-2.

_______________________

Received:

January 23, 2003

Accepted after revision: May 5, 2003

_______________________

Correspondence

address:

Dr. Adilson Prando

Av. Andrade Neves, 707

Campinas, SP, 13013-161, Brazil

Fax: + 55 19 3231-6629

E-mail: aprando@mpc.com.br

EDITORIAL COMMENT

The

authors add important new information to the literature by demonstrating

the variable radiologic features of angiomyolipomas (AMLs). Four specific

categories are defined. The use of this categorization permits the application

of new information concerning these lesions in a more effective manner.

Such a framework has been needed to for appropriate patient care, particularly

since a variety of therapeutic approaches are available.

Pattern

I lesions, which are predominantly fatty, intrarenal and small, represent

an important group. The current paper found no renal cell carcinomas in

patients whose lesions were less than 1.5 cm in size and highly reflective

on ultrasonographic studies. Forman et. al. (1) reviewed 90 pathologically

proven RCCs. In their series, all 5 renal cell carcinomas, which were

less than 1.5 cm in size, were highly echogenic. Thus, one would conclude

from these 2 articles that echogenic masses under 1.5 cm in size are typically

angiomyolipomas, but that when renal cell carcinoma is seen when it is

under 1.5 cm in size it is echogenic and indistinguishable from an AML.

The current article concludes that echogenic masses under 1.5 cm can be

considered AMLs and need no further work-up. A more conservative approach

of verifying this diagnosis with CT or magnetic resonance imaging to identify

the rare, small RCC is standard at many institutions. The cost effectiveness

of this conservative approach remains to be defined.

Pattern

II and III lesions which contain some macroscopic fat can clearly be considered

AMLs. Many physicians would use follow-up studies of these lesions to

define the growth rate of these masses both for prophylactic treatment

of rapidly growing AMLs and to identify the very rare renal cell carcinoma

that contains macroscopic fat.

Pattern

IV lesions which contain no fat and are typically exophytic and perirenal

remain the most challenging category. All of these masses were considered

RCCs and treated surgically which is the standard approach. Biopsy of

renal masses, once considered to be risky because of the possibility of

spread of tumor, has been found to be safe using fine needle technique

(2). Such biopsies are used for such indications including transitional

vs. renal cell carcinoma, lymphoma vs. carcinoma, infection vs. tumor

and to diagnose RCC when a tumor is unresectable. Two angiomyolipomas

were biopsied successfully by Caroli et. al., establishing the diagnosis

(2). The use of biopsy for echogenic masses without fat when seen in an

appropriate setting, such as a middle-aged female or a premenopausal female

with lymphangiomyomatosis (3), remains limited to a few institutions,

but it has great potential.

Finally,

32 of the 53 patients were treated surgically in the current series. In

cases in which hemorrhage or large size are the indications for surgery,

an alternative technique is catheter embolization. (4). This is generally

the initial approach used at our institution in these situations.

The

categorization of AMLs in this article, based on a large series of cases

that were carefully studied, has significant management implications and

will be of use in evaluating therapeutic alternatives.

References

1. Forman HP, Middleton WE, Nelson GL, McClennan BL: Hyperechoic RCC:

increase in detection at US. Radiology 1993; 188: 431-4.

2. Caoili EM, Bude RO, Higgins EJ, Hoff DL, Nghiem HV: Evaluation of sonographically

guided percutaneous core biopsy of renal masses AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;

179: 373-8.

3. Rumacik WM, Bosniak MA, Rosen RJ, Hulnick D: Atypical renal and perirenal

hamartomas associated with lymphangiomyomatosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

1984; 142: 971-82.

4. Han YM, Kim JK, Roh BS, Song HY, Lee JM, Lee YH, et al.: Renal angiomyolipoma:

selective arterial embolization-effectiveness and changes in angiomyogenic

components in long-term follow-up Radiology 1997; 204: 65-70.

Dr.

Arthur T. Rosenfield

Professor of Diagnostic Radiology and Urology

Yale University School of Medicine

New Haven, Connecticut, USA