PSEUDO-MEIGS’

SYNDROME ASSOCIATED TO RENAL PELVIS TUMOR

(

Download pdf )

CHIARA S. TESSMER, FRANKLIN C. BARCELLOS, LUIZ C. FALCHI

Section of Urology, Hospital Santa Casa de Pelotas, Catholic University of Pelotas, Federal University of Pelotas, RS, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

Pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome is associated with tumors different from

the benign ovary tumor, but it has never been described in association

to transitional cell carcinoma.

Case Report: A female 73 year-old patient

presenting pleural effusion nonmetastatic associated with renal pelvis

transitional cell carcinomathat resolved and did not recur after radical

nephroureterectomy.

Comments: Renal pelvis transitional cell

carcinoma can result in the Pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome. Although being

a rare clinical entity, the identification of such syndrome can result

in an accurate diagnosis, leading to an efficient surgical treatment,

without comorbidity for the patient.

Key

words: kidney; carcinoma, transitional cell; Meigs’ syndrome;

pleural effusion

Int Braz J Urol. 2005; 31: 256-8

INTRODUCTION

Meigs & Cass (1) described the Meigs’ syndrome from case reports of patients with right pleural effusion and ascites associated with benign ovary tumor, which were resolved after the removal of the ovarian lesion. The name pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome is used to describe the same clinical situation, but only when it is caused by tumors different from benign ovary tumor (1).

CASE REPORT

Female

patient, 73 year-old, admitted with hematuria, weight loss and dyspnea.

Examination of the thorax showed reduction of the vesicular murmur in

the right pulmonary base. In the right flank a non-painful mass was palpable.

Laboratory tests were performed: hematocrit 29.6%, leukocytes 9.300/mm3,

bacilli 372/mm3, platelet count 628.000/mm3, creatinine 0.6 mg/dL, glucose

96 mg/dL. Analysis of urine presented countless erythrocyte.

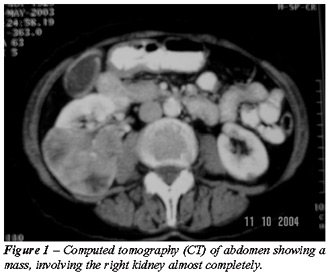

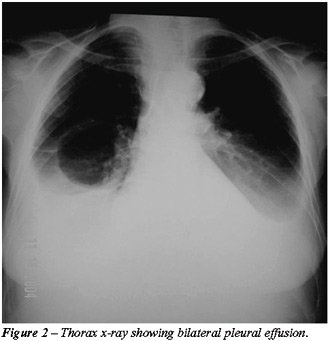

Computed tomography (CT) of abdomen showed

a mass, involving almost completely the right kidney (Figure-1). The chest

radiograph (Figure-2) and the CT scan demonstrated bilateral pleural effusion.

Bone scintigraphy was negative for metastasis; the echocardiography was

normal.

Carrying out bilateral thoracocentesis.

Gram, BAAR research, cultures of fungus and bacteria were all negatives.

Results for total proteins were 3.5g/dL (serum = 5.5 g/dL) and the DHL

was 156 u/L (serum = 212 u/L). Cytologic evaluation evidenced countless

erythrocyte and absence of malignant cells. Diagnosis of the biopsy was

bilateral chronic pleurisy. Two weeks after draining, patient’s

dyspnea returned. The CT scan evidenced pleural effusion. Therefore, the

patient was submitted to a thoracoscopy, but there was no alteration in

previous results.

Right nephroureterectomy was performed.

The pathological result was renal pelvis transitional cell carcinoma;

grade II of ASH. The patient had good postoperative evolution with complete

pleural effusion disappearance.

After 7 months of postoperative, patient

remained asymptomatic, with image tests without pleural liquid reaccumulation,

or others alterations.

COMMENTS

Renal

pelvis carcinomas more frequently metastasize in-continuity, but also

by hematogenic and lymphatic routes. The most common locals of hematogenic

dissemination are the liver, lungs, and bones (2). Although pulmonary

metastasis is common, metastases to pleura, as well as pleural effusion,

have not been described in association to transitional cell carcinoma.

The pleural effusion develops due to changes

in the capillary hemodynamic; when appearing as an exudate suggests a

local cause. Most of the times, the cause of the effusion becomes evident

after a proper investigation. In the absence of post-pneumonic effusion,

generalized hypoproteinemia or cardiac insufficiency, metastatic carcinoma,

tuberculosis, pulmonary infarct, and mesothelioma must be excluded (2).

Once the above causes were excluded, 2 biopsies

of pleura and 2 CT scanning were carried out to assure nonexistence of

pleural metastases. Besides, the hemorrhagic appearance of the liquid

could indicate the malignant nature; however, successive analyses of the

liquid and biopsy had been all negative to the presence of malignant cells,

attesting that the bloody liquid aspect did not demonstrate, necessarily,

the presence of malignancy (2).

The pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome has already

been reported associated with many different tumors, but there was just

one reported case associating the syndrome with renal neoplasm, in the

literature (2).

The pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome cases have

in common the cure of the pleural effusion after the removal of the lesion.

Such straight connection allows classifying different tumors as being

the cause of only one syndrome (1,3).

Therefore, the renal pelvis transitional

cell carcinomacan result in the pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome. The identification

of such syndrome results in an accurate diagnosis, leading to an efficient

surgical treatment, without comorbidity for the patient.

_______________________

Professor Heitor A. Jammke

contributed to this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Feldman ED, Hughes MS, Stratton P, Schrump DS, Alexander HR Jr: Pseudo-Meigs‘syndrome secondary to isolated colorectal metastasis to ovary: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2004; 93: 248-51.

- Dinney CP, Norman RW: Contralateral pleural effusion secondary to nonmetastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1990; 143: 1002-3.

- Ohsawa T, Ishida H, Nakada H, Inokuma S, Hashimoto D, Kuroda H, et al.: Pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome caused by ovarian metastasis from colon cancer: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003; 33: 387-91.

________________________

Received:

February 14, 2005

Accepted after revision: May 3, 2005

_______________________

Correspondence address:

Dr. Chiara Scaglioni Tessmer

Av. São Francisco de Paula, 2592

Pelotas, RS, 96080-730, Brazil

Phone: +55 53 228-4199

E-mail: chiara_tessmer@yahoo.com.br