VIDEO

ENDOSCOPIC INGUINAL LYMPHADENECTOMY (VEIL): MINIMALLY INVASIVE RESECTION

OF INGUINAL LYMPH NODES

(

Download pdf )

M. TOBIAS-MACHADO, ALESSANDRO TAVARES, WILSON R. MOLINA JR, PEDRO H. FORSETO JR, ROBERTO V. JULIANO, ERIC R. WROCLAWSKI

Section of Urology, ABC Medical School, Santo Andre, Sao Paulo, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Objectives:

Describe and illustrate a new minimally invasive approach for the radical

resection of inguinal lymph nodes.

Surgical Technique: From the experience

acquired in 7 operated cases, the video endoscopic inguinal lymphadenectomy

(VEIL) technique was standardized in the following surgical steps: 1)

Positioning of the inferior member extended in abduction, 2) Introduction

of 3 work ports distal to the femoral triangle, 3) Expansion of the working

space with gas, 4) Retrograde separation of the skin flap with a harmonic

scalpel, 5) Identification and dissection of the long saphenous vein until

the oval fossa, 6) Identification of the femoral artery, 7) Distal ligature

of the lymph node block at the femoral triangle vertex, 8) Liberation

of the lymph node tissue up to the great vessels above the femoral floor,

9) Distal ligature of the long saphenous vein, 10) Control of the saphenofemoral

junction, 11) Final liberation of the surgical specimen and endoscopic

view showing that all the tissue of the region was resected, 12) Removal

of the surgical specimen through the initial orifice, 13) Vacuum drainage

and synthesis of the incisions.

Comments: The VEIL technique is feasible

and allows the radical removal of inguinal lymph nodes in the same limits

of conventional surgery dissection. The main anatomic repairs of open

surgery can be identified by the endoscopic view, confirming the complete

removal of the lymphatic tissue within the pre-established limits. Preliminary

results suggest that this technique can potentially reduce surgical morbidity.

Oncologic follow-up is yet premature to demonstrate equivalence on the

oncologic point of view.

Key

words: penile cancer; groin; lymphadenectomy; video-assisted

surgery

Int Braz J Urol. 2006; 32: 316-21

INTRODUCTION

Inguinal

lymphadenectomy is indicated in patients presenting penile and urethral

cancer, after local treatment, when there is a lymph node mass that does

not disappear with antibiotic therapy, or when palpable lymph nodes appear

in the postoperative follow-up or when there are risk factors for the

development of inguinal metastasis (prophylactic lymphadenectomy). This

operation is frequently performed through a bilateral inguinal incision

from the iliac crest until the pubic tubercle. There is, however, a high

morbidity regarding the dissected skin flap to access the inguinal lymph

nodes, as well as skin necrosis and local infection, and depending on

the extension of the lymphadenectomy, higher frequency of edema in inferior

members, lymphocele, lymphedema and lymphorea (1).

Trying to reduce the morbidity of this radical

operation the literature shows surgical alternatives that aim at restricting

the inguinal dissection area. However, all techniques present different

local recurrence rates, probably due to false negative results (2).

Video-assisted surgery has been employed

in the iliac and retroperitoneal lymph nodes approach, reducing postoperative

discomfort, minimizing anatomic sequels and allowing a faster recuperation

of patients, keeping the functional results of conventional surgery for

the majority of indications.

We aimed at describing and illustrating

the technical details of a minimally invasive procedure for inguinal lymphadenectomy

recently described in the clinical scenario (3). This technique duplicates

the principles of conventional technique, promoting a radical resection

of inguinal lymph nodes, with encouraging preliminary results regarding

the reduction of surgical morbidity.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

The

technique described was developed in a prospective protocol that includes

up to now 7 patients presenting penile spinocellular carcinoma, without

palpable lymph nodes or that had a regression after a 6-week-antibiotic

therapy. All patients had an indication of bilateral lymphadenectomy due

to the presence of risk factors for lymph node dissemination such as:

clinical stage > T1 or information regarding the initial biopsy such

as histological grade > 1, lymphatic or vascular invasion.

After signature of the informed consent

the patients were submitted to classic open surgery in one of the members

(control group) and a video-assisted surgery, named video endoscopic inguinal

lymphadenectomy (VEIL) in the other member (group of the technique to

be assessed).

Control

Member

For the open conventional surgery, we have

used the superficial inguinal lymphadenectomy technique and deep in the

Dressler triangle, medial to the femoral artery, without the preservation

of the long saphenous vein through a large inguinotomy.

Video

Endoscopic Inguinal Lymphadenectomy (VEIL)

1 – Positioning and preparation of

the inferior member - The leg is folded over the thigh in a way to put

in evidence the femoral triangle that is marked with ink over the skin.

After the marking, the leg is extended and fixed to the table with abduction

and light external rotation of the thigh. The video monitor is positioned

at the contralateral side to the operated one at the patient’s pelvic

waist.

2 – Introduction of the ports - At

2 cm of the femoral triangle vertex in a distal sense an incision of 1.5

cm in the skin and in the subcutaneous tissue until the Scarpa’s

fascia is performed, being developed a subcutaneous plan with scissors

and later with a digital maneuver in the largest possible extension. A

second incision of 1 cm, at around 2 cm above and 6 cm medially to the

first incision, to the introduction of a 10 mm port. It is possible to

identify the trajectory of the saphenous vein through this access. A laterally

symmetric position 5 mm port is introduced for graspers, dissection tweezers

and scissors. At the initial access, a 10 mm Hasson trocar is preferably

introduced. All the ports are fixed to the skin through a purse-string

suture with cotton 0. At the initial port, we introduce a 0-degree optic,

and at the medial port, we introduce the tweezers of the harmonic scalpel

and the clipper. The surgeon and the camera operator are positioned laterally

to the operated member.

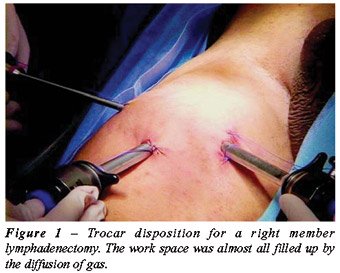

3 – Expansion with gas of the working

space – The creation of a working space is completed through the

initial insufflation of CO2 with a 15-mmHg pressure, with its fast diffusion,

being able to keep the pressure at 5-10 mmHg during the procedure (Figure-1).

Transillumination allows a good orientation regarding the progression

of the dissection area.

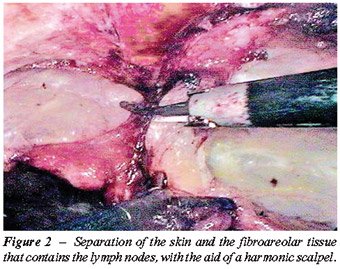

4 – Retrograde separation of the skin

flap – This time is fundamental to the success of the procedure

and is performed with a harmonic scalpel. Initially we perform the separation

between the skin and the fibroareolar tissue that contains the superficial

lymph nodes until the external oblique muscle fascia on the superior part

(Figure-2). Afterwards we proceed to the dissection of the fundamental

parameters, having as a limit the long adductor muscle and its fascia

medially, the sartorius muscle and its fascia laterally, and the inguinal

ligament superiorly. It is possible to identify branches of the femoral

nerve that should be preserved.

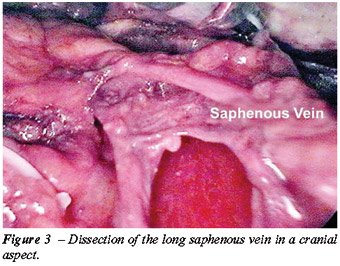

5 – Identification and cranial dissection

of long saphenous vein until the oval fossa (Figure-3).

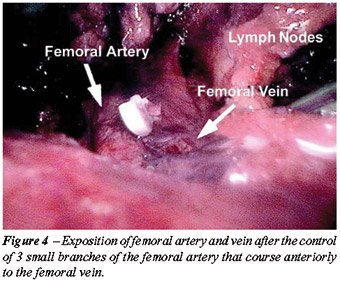

6 – Identification of the femoral

artery – After the identification of the femoral artery and the

opening of the femoral vein sheath we define the lateral limit of the

dissection, allowing the access to the deep cervical lymph nodes (Figure-4).

At this moment it can be necessary to control with 1 or 2 branch clips

coming from the femoral artery that run anteriorly to the femoral vein.

7 – Distal ligature of the lymph node

block at the femoral triangle vertex – the fibroareolar tissue is

dissected with a harmonic scalpel and the control of the final section

at the femoral triangle vertex is obtained with clips.

8 – Liberation of the lymph nodes

until the great vessels above the femoral floor. During this operative

time, the use of the harmonic scalpel and a careful manipulation of the

specimen in areas near the veins are necessary to avoid vascular lesion.

As in the conventional technique, the aim is to skeletonize the femoral

veins, resecting all local lymphatic tissue (Figure-4).

9 – Distal ligature of the long saphenous

vein with clips

10 – Control of the branches and the

long saphenofemoral junction with a harmonic scalpel and metallic clips

- most part of the branches of the long saphenous vein are controlled

only by the harmonic scalpel. Branches larger than 4 mm need clips for

the ligature. The entrance of the long saphenous vein in the femoral vein

should be well dissected and controlled preferably with polymer clips

(Figure-5).

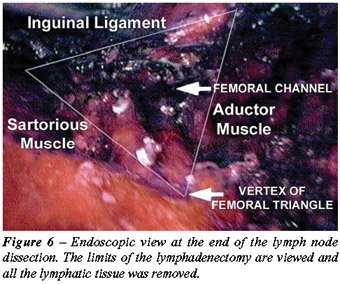

11 – Final liberation of the specimen

medially to the long saphenous vein, ligating the proximal portion of

the lymph nodes at the deep region of the femoral channel with clips.

After completing the liberation of the specimen, the endoscope view attests

that all the tissue of the region was completely resected (Figure-6).

12 – Removal of the surgical specimen

by the 15 mm incision. In case the specimen is of large dimensions, it

can be put inside a bag and latter removed.

13 – Vacuum drainage through the 5

mm orifice and suture of the larger incisions (Figure-7).

COMMENTS

Approximately

30% of the patients with penile spinocellular carcinoma present lymph

node metastasis at the time of the diagnosis. Bilateral inguinal lymphadenectomy

is a procedure accepted as a prognostic and therapeutic value in cases

of penile and urethral spinocellular carcinoma with high risk of developing

metastasis (1). However, morbidity associated to this surgery is high,

being questioned its need mainly when the intention is prophylactic. In

the past, due to the data presented, some centers adopted a conservative

conduct through a rigid clinic follow-up.

Contemporary works have demonstrated that

prophylactic lymphadenectomy offers better survival results than salvage

lymphadenectomy performed in those patients where we have initially opted

for a rigorous observation. Besides that, they have also showed that the

non-controlled lymph node disease was an important cause for morbidity

and mortality in patients with penile cancer.

Before the dilemma of offering radical surgery

with a significant morbidity to 70% of the patients in an unnecessary

way or harm the survival of 30% of the patients submitted to the surveillance

regimen, new alternatives were reported in literature. The techniques

described in the last 20 years to reduce the morbidity are based on the

reduction of inguinal dissection templates. Even though the evident reduction

of operation complications described both with simplified lymphadenectomy

and with the employment of sentinel lymph node with radioisotopes, some

authors believe that its higher morbidity could be related to a rate of

15% of late recurrence of the disease with possible involvement of these

individual’s survival (2).

The present work was motivated by the attempt

to reduce the complications of inguinal lymphadenectomy, based on the

initial works of video-assisted saphenous vein resection, subcutaneous

endoscopic procedures used in plastic surgery and video endoscopic resection

of axillary lymph nodes. (4-6).

Recently, Bishoff et al. described the possibility

of modified dissection of inguinal lymph nodes through endoscopic subcutaneous

access performed in 2 human cadavers and in 1 patient with penile cancer

stage T3N1M0. Dissection was possible on the human cadavers but it was

however not possible in the patient due to the adherence of the enlarged

lymph nodes to the femoral veins (7). After some technical changes we

have performed, to this date, the surgery in a safe and efficient way

in 7 patients with indication of prophylactic lymphadenectomy.

The idealized technique allows a complete

excision of inguinal lymph nodes, the way it is done in conventional surgery,

allowing an initial impression of benefit regarding the lower postoperative

morbidity when compared to the conventional technique. The medium 120

minutes operative time is still superior to the open technique; however,

we should consider the learning curve. Surprisingly enough, there were

no skin complications. The presence of infraumbilical subcutaneous emphysema

of spontaneous resolution is the rule, being uncommon the clinical manifestation.

Hypercarbia can occur intraoperatively, being completely reversible with

hyperventilation, without the need for conversion. In a subjective analysis,

all patients preferred endoscopic surgery. Pathological exam of surgical

specimens showed that the medium number of lymph nodes excised did not

differ from that obtained with conventional surgery.

We attribute this preliminary result to

the following technical principles: 1) Non use of electrical current and

mechanical retraction with subcutaneous retractors. The retraction is

performed atraumatically by the gas, minimizing cutaneous lesions, 2)

Short incisions outside the area of the great vessels allow a shorter

area of lesion of the separated flap and probably less chance of infection,

besides making unnecessary the rotation of the sartorius muscle flap to

recover femoral veins, 3) Control of the lymph nodes, visualized by magnification,

with harmonic scalpel and clips. The proximal and distal ligature of major

channels is fundamental to avoid important lymphoceles or lymphorea.

The presence of skin adherences or palpable

mass of lymph nodes, predictive factors for technical difficulty, were

excluded from this initial study which objectives were to assess the possibility

and technical equivalence to classical lymph nodes resection.

CONCLUSIONS

The

VEIL technique is feasible and allows the radical removal of inguinal

lymph nodes at the same dissection template as conventional surgery. The

main anatomic repairs of open surgery can be identified in an endoscopic

view, confirming the complete removal of the lymphatic tissue within the

pre-established limits.

Preliminary results with this new endoscopic

approach for inguinal lymphadenectomy are promising, with potential to

reduce morbidity. It seems not to change expected oncologic results with

the conventional technique, but the follow-up is still short for definite

conclusions.

Future studies and validation by other authors

will determine the real role of this procedure in the staging and treatment

of patients with penile and urethral spinocellular carcinoma.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Bevan-Thomas R, Slaton JW, Pettaway CA: Contemporary morbidity from lymphadenectomy for penile squamous cell carcinoma: the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Experience. J Urol. 2002; 167: 1638-42.

- d’Ancona CA, de Lucena RG, Querne FA, Martins MH, Denardi F, Netto NR Jr: Long-term follow-up of penile carcinoma treated with penectomy and bilateral modified inguinal lymphadenectomy. J Urol. 2004; 172: 498-501; discussion 501.

- Machado MT, Tavares A, Molina Jr WR, Zambon JP, Forsetto Jr P, Juliano RV, Wroclawski ER: Comparative study between videoendoscopic radical inguinal lymphadenectomy(VEIL) and standard open lymphadenectomy for penile cancer: preliminary surgical and oncological results. J Urol. 2005; 173: 226, Abst 834.

- Folliguet TA, Le Bret E, Moneta A, Musumeci S, Laborde F: Endoscopic saphenous vein harvesting versus ‘open’ technique. A prospective study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1998; 13: 662-6.

- Dardour JC, Ktorza T: Endoscopic deep periorbital lifting: study and results based on 50 consecutive cases. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2000; 24: 292-8.

- Avrahami R, Nudelman I, Watenberg S, Lando O, Hiss Y, Lelchuk S: Minimally invasive surgery for axillary dissection. Cadaveric feasibility study. Surg Endosc. 1998; 12: 466-8.

- Bishoff JA, Lackland AF, Basler JW, Teichman JM, Thompson IM: Endoscopy subcutaneous modified inguinal lymph node dissection (ESMIL) for squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. J Urol. 2003: 169; Supl 4: 78.

____________________

Accepted

after revision:

January 15, 2006

_______________________

Correspondence address:

Dr. Marcos Tobias-Machado

Rua Graúna, 104/131

São Paulo, SP, 04514-000, Brazil

Fax: + 55 11 3288-1003

E-mail: tobias-machado@uol.com.br