INFLAMMATORY

ATROPHY ON PROSTATE NEEDLE BIOPSIES: IS THERE TOPOGRAPHIC RELATIONSHIP

TO CANCER?

(

Download pdf )

ATHANASE BILLIS, LEANDRO L. L. FREITAS, LUIS A. MAGNA, UBIRAJARA FERREIRA

Departments of Anatomic Pathology (AB, LLLF), Genetics and Biostatistics (LAM), and Urology (UF), School of Medicine, State University of Campinas (Unicamp), Campinas, Sao Paulo, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

Chronic inflammation of longstanding duration has been linked to the development

of carcinoma in several organ systems. It is controversial whether there

is any relationship of inflammatory atrophy to prostate cancer. It has

been suggested that the proliferative epithelium in inflammatory atrophy

may progress to high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and/or

adenocarcinoma. The objective of our study is to compare on needle prostate

biopsies of patients showing cancer the topographical relation of inflammatory

atrophy and atrophy with no inflammation to adenocarcinoma.

Materials and Methods: The frequency and

extent of the lesions were studied on 172 needle biopsies of patients

with prostate cancer. In cores showing both lesions, the foci of atrophy

were counted. Clinicopathological features were compared according to

presence or absence of inflammation.

Results: Considering only cores showing

adenocarcinoma, atrophy was seen in 116/172 (67.44%) biopsies; 70/116

(60.34%) biopsies showed atrophy and no inflammation and 46/116 (39.66%)

biopsies showed inflammatory atrophy. From a total of 481 cores in 72

biopsies with inflammatory atrophy 184/481 (38.25%) cores showed no atrophy;

166/481 (34.51%) cores showed atrophy and no inflammation; 111/481 (23.08%)

cores showed both lesions; and 20/481 (4.16%) showed only inflammatory

atrophy. There was no statistically significant difference for the clinicopathological

features studied.

Conclusion: The result of our study seems

not to favor the model of prostatic carcinogenesis in which there is a

topographical relation of inflammatory atrophy to adenocarcinoma.

Key

words: prostate; inflammation; atrophy; carcinoma; needle biopsy

Int Braz J Urol. 2007; 33: 355-63

INTRODUCTION

Chronic inflammation of longstanding duration has been linked to the development of carcinoma in several organ systems (1-3). In the prostate, it is controversial whether there is any relationship of atrophy with inflammation (or inflammatory atrophy) to prostate cancer (4-10). De Marzo et al. (5) propose that there is a topographical relation with morphological transitions within the same acinar/duct unit, between high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) and inflammatory atrophy which occur frequently (7). This finding supports a model whereby the proliferative epithelium in inflammatory atrophy may progress to HGPIN and subsequently to adenocarcinoma. The aim of this study is to compare in cores of needle biopsies of patients showing prostate cancer the topographic relation of inflammatory atrophy and atrophy with no inflammation to adenocarcinoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The

material of this retrospective study was obtained from 172 consecutive

men with cancer on needle prostate biopsies and subsequently submitted

to radical retropubic prostatectomy.

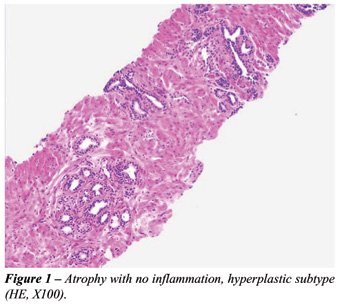

Both partial and complete prostatic atrophy

were considered. Partial prostatic atrophy was diagnosed according to

criteria described by Oppenheimer et al. (11) and complete atrophy by

criteria described by Billis (4). Three histological subtypes were identified:

simple atrophy, hyperplastic atrophy (or postatrophic hyperplasia) (Figure-1),

and sclerotic atrophy. Elastosis of the stroma was a useful microscopic

feature for the identification of prostatic atrophy of any subtype (12).

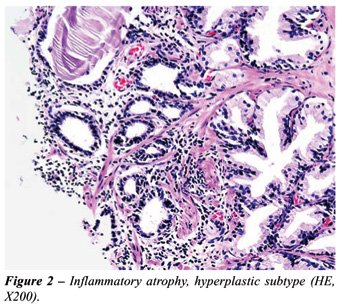

Inflammatory atrophy (prostatic atrophy

with inflammation) - Both inactive and active inflammation were considered.

Inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes, plasmacytes or macrophages was

considered inactive. The infiltrate was considered active whenever neutrophils

were seen in the stroma. All grades of inflammation were considered according

to a modified consensus development of a histopathological classification

system for chronic prostatic inflammation (13): mild (scattered individual

inflammatory cells), moderate (clusters of inflammatory cells) and severe

(confluent sheets of inflammatory cells) in areas of prostatic atrophy

of any kind: simple, hyperplastic (Figure-2) or sclerotic.

According to the pathologic findings, patients

were stratified into group A (biopsies with atrophy and no inflammation),

and group B (biopsies with inflammatory atrophy).

The frequency of atrophy was evaluated considering

all cores of the biopsy as well as only the cores showing adenocarcinoma.

Extent of inflammatory atrophy and atrophy with no inflammation was evaluated

according to the number of cores showing the lesion. In group B, we counted

the cores showing only inflammatory atrophy, cores showing atrophy and

no inflammation, and cores showing both lesions. In cores showing both

inflammatory atrophy and atrophy with no inflammation, the foci of each

lesion were counted using an image analyzer (ImageLab-2000).

The clinicopathological features included

age of the patients, preoperative PSA, and biopsy Gleason score.

The data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney

test for comparison of continuous variables with P < 0.05 being considered

statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using

Statistica 5.5 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

RESULTS

A

total of 1,088 cores (mean, median and range 6.32, 6 and 1-13, respectively)

were obtained from 172 needle biopsies of patients with prostate cancer.

Considering all cores of the biopsy, atrophy was seen in 144/172 (83.72%)

biopsies; 72/144 (50%) biopsies showed atrophy with no inflammation and

72/144 (50%) biopsies showed inflammatory atrophy. In 57/72 (79.16%) biopsies

with inflammatory atrophy inflammation was inactive, and in 15/72 (20.83%)

biopsies inflammation was active.

Considering only cores showing adenocarcinoma,

atrophy was seen in 116/172 (67.44%) biopsies; 70/116 (60.34%) biopsies

showed atrophy with no inflammation and 46/116 (39.66%) biopsies showed

inflammatory atrophy (Table-1).

There was a total of 481 cores in the 72

biopsies with inflammatory atrophy; 184/481 (38.25%) cores showed no atrophy;

166/481 (34.51%) cores showed atrophy and no inflammation; 111/481 (23.08%)

cores showed both lesions; and, 20/481 (4.16%) cores showed only inflammatory

atrophy (Table-2). In the cores showing both lesions, inflammatory atrophy

was seen in 193/398 (48.49%) foci, and atrophy with no inflammation was

seen in 205/398 (51.51%) foci.

Table-3 shows the clinicopathologic features

by groups A and B according to age, preoperative PSA and biopsy Gleason

score. There was no statistically significant difference between patients

showing atrophy and no inflammation (group A) and patients showing inflammatory

atrophy (group B).

COMMENTS

Prostatic

atrophy is one of the most frequent mimics of prostatic adenocarcinoma

(14). It occurs most frequently in the posterior lobe or peripheral zone

(15) and gained importance with the increasing use of needle biopsies

for the detection of prostatic carcinoma (16). The frequency of the lesion

in autopsies is 85% and increases with age (4). The etiopathogenesis of

prostatic atrophy is unknown. Compression due to hyperplastic nodules,

inflammation, hormones, nutritional deficiency, systemic or local ischemia,

are all factors that may play a role in the pathogenesis of atrophy (4,14,15,17,18).

The histologic subtypes of prostatic atrophy do not represent distinct

entities but a morphologic continuum of acinar atrophy. Subtyping atrophy

is useful not only for its recognition, and for distinguishing it from

prostate cancer (4,16).

Chronic inflammation of longstanding duration

has been linked to the development of carcinoma in several organ systems

(1-3). In the prostate, it is controversial whether there is any relationship

of inflammatory atrophy to prostate cancer (4-10). The term “proliferative

inflammatory atrophy” was proposed by De Marzo et al. (5) to designate

discrete foci of proliferative glandular epithelium with the morphological

appearance of simple atrophy or postatrophic hyperplasia occurring in

association with inflammation. According to these authors the morphology

of proliferative inflammatory atrophy is consistent with McNeal’s

description of postinflammatory atrophy (19), with that of chronic prostatitis

described by Bennett et al. (20), and with the lesion referred to previously

as “lymphocytic prostatitis” by Blumenfeld et al. (21). De

Marzo et al. (5) and Putzi and De Marzo (7) suggest that proliferative

atrophy may indeed give rise to carcinoma directly or that proliferative

atrophy may lead to carcinoma indirectly via development into HGPIN. This

hypothesis by the authors is based on three separate findings providing

supportive evidence: 1) A topographical relation with morphologic merging

between proliferative inflammatory atrophy and HGPIN in 34% of the inflammatory

atrophy lesions; 2) The phenotype of many of the cells in inflammatory

atrophy is most consistent with that of an immature secretory-type cell,

similar to that for the cells of HGPIN; and 3) proliferative inflammatory

atrophy, HGPIN, and carcinoma all occur with high prevalence in the peripheral

zone and low prevalence in the central zone of the human prostate.

Favoring a link of inflammation to prostate

adenocarcinoma, Cohen et al. (22) found a positive association between

Propionibacterium acnes and prostatic inflammation, which may be implicated

in the development of prostate cancer. However, the authors comment that

it is possible that prostatic inflammation may also be caused by other

microorganisms which could not be identified by the study, for example

obligate anerobes or species which are difficult to culture under laboratory

conditions. They also comment on a second important limitation of the

study related to the lack of appropriate negative controls such as prostate

tissue from patients without inflammation, atrophy and cancer.

Other studies are at odds with the findings

of De Marzo et al. (5) and Putzi and De Marzo (7). In 100 consecutively

autopsied men more than 40 years of age, Billis (4) studied the etiopathogenesis

of atrophy and its possible potential as a precancerous lesion. There

was no statistically significant relation of atrophy to histologic (incidental)

carcinoma or HGPIN. The author concluded that prostatic atrophy probably

is not a premalignant lesion. In this autopsy study, prevalence of atrophy

increased with age and chronic ischemia caused by local intense arteriosclerosis

seemed to be a potential factor for its pathogenesis. In a subsequent

study, Billis and Magna (9) stratified the 100 prostates into group A

(atrophy without inflammation) and group B (inflammatory atrophy). The

groups were correlated to age, race, histologic (incidental) carcinoma,

HGPIN, and extent of both these latter lesions. There was no statistically

significant difference between groups A and B for all the variables studied.

Neither a topographical relation nor a morphologic transition was seen

between prostatic atrophy and histologic carcinoma or HGPIN. The authors

concluded that inflammatory atrophy does not appear to be associated with

cancer or HGPIN.

Anton et al. (6) studying 272 radical prostatectomies

and 44 cystoprostatectomies concluded that postatrophic hyperplasia is

a relatively common lesion present in about one-third of prostates, either

with or without prostate carcinoma. The authors found no association between

the presence of postatrophic hyperplasia and the likelihood of cancer

and no topographic association between postatrophic hyperplasia and prostate

carcinoma foci.

Bakshi et al. (8) studied 79 consecutive

prostate biopsies: 54% of initial biopsies were benign, 42% of the cases

showed cancer, and 4% HGPIN or atypia. Postatrophic hyperplasia was seen

in 17% of benign initial biopsies with available follow-up. Of these,

75% had associated inflammation. There was no significant difference in

the subsequent diagnosis of prostate cancer for groups with postatrophic

hyperplasia, partial atrophy, atrophy, or no specific abnormality. The

authors concluded that the subcategories of atrophy do not appear to be

associated with a significant increase in the risk of diagnosis of prostate

cancer subsequently.

Postma et al. (10) evaluated whether the

incidence of atrophy reported on sextant biopsies is associated with subsequent

prostate cancer detection. The authors concluded that atrophy is a very

common lesion in prostate biopsy cores (94%). Atrophy in an asymptomatic

population undergoing screening was not associated with a greater prostate

cancer or HGPIN incidence during subsequent screening rounds.

In the present study, from a total of 172

needle biopsies of men with prostate cancer, 144/172 showed atrophy; 72/144

(50%) biopsies showed atrophy and no inflammation and 72/144 (50%) biopsies

showed inflammatory atrophy. However, considering only cores with cancer,

atrophy was seen in 116/172 (67.44%) biopsies; 70/116 (60.34%) biopsies

showed atrophy and no inflammation and 46/116 (39.66%) biopsies showed

inflammatory atrophy. This finding seems to contradict the topographical

model by De Marzo et al. (5) whereby inflammatory atrophy may progress

directly to adenocarcinoma or indirectly via development to HGPIN. In

cores with adenocarcinoma it would be expected a higher frequency of inflammatory

atrophy. Another relevant finding in our study was the evaluation of the

extension of inflammatory atrophy in the 481 cores of the 72 biopsies

showing this lesion. In only 20/481 (4.16%) cores inflammatory atrophy

was the only lesion present. Most frequently cores showed either atrophy

with no inflammation (166/481, 34.51%) or both lesions (111/481, 23.08%).

A criticism to our findings is that a thin prostate needle biopsy may

not represent a real topographic relation between lesions if compared

to findings in large specimens such as radical prostatectomy or autopsy

prostates. In the study on autopsies with step-sectioning of the prostate,

a topographic relation of inflammatory atrophy and HGPIN and/or histologic

adenocarcinoma was also not found (9).

There was no statistically significant difference

for age (P = 0.7487), preoperative PSA (P = 0.7950), and Gleason score

in the biopsy (P = 0.5143) between patients with atrophy and no inflammation

and patients with inflammatory atrophy probably indicating no difference

in temporal onset and aggressiveness of the tumor in this two groups.

CONCLUSION

The result of our study seems not to favor the model of prostatic carcinogenesis in which there is a topographical relation of inflammatory atrophy to adenocarcinoma. In cores with adenocarcinoma, atrophy with no inflammation was more frequently seen than inflammatory atrophy, and in biopsies with inflammatory atrophy, only 4.16% of the cores showed this lesion as the only finding.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Ames BN: Mutagenesis and carcinogenesis: endogenous and exogenous factors. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1989; 14: 66-77.

- Weitzman SA, Gordon LI: Inflammation and cancer: role of phagocyte-generated oxidants in carcinogenesis. Blood. 1990; 76: 655-63.

- Bartsch H, Frank N: Blocking the endogenous formation of N-nitroso compounds and related carcinogens. IARC Sci Publ. 1996; 139: 189-201.

- Billis A: Prostatic atrophy: an autopsy study of a histologic mimic of adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 1998; 11: 47-54.

- De Marzo AM, Marchi VL, Epstein JI, Nelson WG: Proliferative inflammatory atrophy of the prostate: implications for prostatic carcinogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1999; 155: 1985-92.

- Anton RC, Kattan MW, Chakraborty S, Wheeler TM: Postatrophic hyperplasia of the prostate: lack of association with prostate cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999; 23: 932-6.

- Putzi MJ, De Marzo AM: Morphologic transitions between proliferative inflammatory atrophy and high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Urology. 2000; 56: 828-32.

- Bakshi NA, Pandya S, Schervish EW, Wojno KJ: Morphologic features and clinical significance of post-atrophic hyperplasia in biopsy specimens of prostate. Mod Pathol. 2002; 15: 154A.

- Billis A, Magna LA: Inflammatory atrophy of the prostate. Prevalence and significance. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003; 127: 840-4.

- Postma R, Schroder FH, van der Kwast TH: Atrophy in prostate needle biopsy cores and its relationship to prostate cancer incidence in screened men. Urology. 2005; 65: 745-9.

- Oppenheimer JR, Wills ML, Epstein JI: Partial atrophy in prostate needle cores: another diagnostic pitfall for the surgical pathologist. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998; 22: 440-5.

- Billis A, Magna LA: Prostate elastosis: a microscopic feature useful for the diagnosis of postatrophic hyperplasia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000; 124: 1306-9.

- Nickel JC, True LD, Krieger JN, Berger RE, Boag AH, Young ID: Consensus development of a histopathological classification system for chronic prostatic inflammation. BJU Int. 2001; 87: 797-805.

- Srigley JR: Benign mimickers of prostatic adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2004; 17: 328-48.

- Liavag I: Atrophy and regeneration in the pathogenesis of prostatic carcinoma. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1968; 73: 338-50.

- Cheville JC, Bostwick DG: Postatrophic hyperplasia of the prostate. A histologic mimic of prostatic adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995; 19: 1068-76.

- Rich AR: On the frequency of occurrence of occult carcinoma of the prostate. J Urol.1935; 33: 3.

- Ro JY, Sahin AA, Ayala AG. Tumors and tumorous conditions of the male genital tract. In: Fletcher CDM (eds.), Diagnostic Histopathology of Tumors. New York, Churchill Livingstone. 1995; pp. 521-3.

- McNeal JE: Prostate. In: Sternberg SS (ed.), Histology for Pathologists. second edition. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven. 1997; pp. 997-1017.

- Bennett BD, Richardson PH, Gardner WA Jr. Histopathology and cytology of prostatitis. In: Lepor H, Lawson RK (eds.), Prostate Diseases. Philadelphia, WB Saunders Co. 1993; pp. 399-414.

- Blumenfeld W, Tucci S, Narayan P: Incidental lymphocytic prostatitis. Selective involvement with nonmalignant glands. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992; 16: 975-81.

- Cohen RJ, Shannon BA, McNeal JE, Shannon T, Garrett KL: Propionibacterium acnes associated with inflammation in radical prostatectomy specimens: a possible link to cancer evolution? J Urol. 2005; 173: 1969-74.

____________________

Accepted after revision:

December 30, 2006

_______________________

Correspondence address:

Dr. Athanase Billis

Dep. de Anatomia Patologica

Fac. de Ciências Médicas - UNICAMP

Caixa Postal 6111

Campinas, SP, 13084-971, Brazil

E-mail: athanase@fcm.unicamp.br

EDITORIAL COMMENT

High-grade

prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) is the most likely precursor

of prostatic adenocarcinoma, according to virtually all available evidence.

There are other possible findings in the prostate that may be premalignant

(Low-grade PIN, inflammatory atrophy, malignancy-associated foci, and

atypical adenomatous hyperplasia), but the data for them are much less

convincing than that for HGPIN (1).

The

paper by Athanase Billis and collaborators entitled “Inflammatory

Atrophy on Prostate Needle Biopsies: Is There Topographic Relationship

to Cancer?” deals with the interesting topic of preneoplastic lesions

and conditions of the prostate, in particular with proliferative inflammatory

atrophy (2). The objective of their study was to compare on needle prostate

biopsies of patients showing cancer the topographical relation of inflammatory

atrophy and atrophy with no inflammation to adenocarcinoma. The result

of their study did not favor the model of prostatic carcinogenesis in

which there is a topographical relation of inflammatory atrophy to adenocarcinoma.

Dr Billis’ study does not exclude that inflammatory atrophy could

be an early step in the development of prostate cancer and one of the

possible preneoplastic conditions and lesions that precede the appearance

of cancer.

Low-grade

PIN (LGPIN) - Earlier morphometric and immunohistochemical studies showed

that LGPIN has features that are intermediate between normal tissue and

HGPIN (1). Little information on LGPIN has been accumulated in recent

times. This is probably due to the fact, while HGPIN in needle biopsy

tissue is a risk factor for the subsequent detection of carcinoma, LGPIN

is not. Currently, LGPIN is not documented in pathology reports due a

relatively low risk of cancer following re-biopsy.

In

Bostwick’s progression model of PIN to carcinoma, the transition

between normal, low-grade PIN, high-grade PIN, and then carcinoma is continuous

(3). Few epidemiologic, morphologic, or molecular genetic studies have

examined the relation between low and high-grade PIN development. In part,

this relates to the difficulty in distinguishing low-grade PIN from normal

tissue on the one hand and high-grade PIN on the other. Nevertheless,

Putzi and De Marzo (4) found that lesions that could be considered low-grade

PIN often coexisted with high-grade PIN, suggesting either that high-grade

PIN is derived from low-grade PIN or that high and low grade PIN arise

concomitantly.

Focal

Prostate Atrophy as a Morphological Manifestation of a “Field Effect”

and a Potential Prostate Cancer Precursor - Pathologists have long recognized

focal areas of epithelial atrophy in the prostate that appear more commonly

in the peripheral zone of the prostate. These lesions may be associated

with chronic inflammation, and less commonly with acute inflammation (5).

The term proliferative inflammatory atrophy (PIA) has been proposed (5).

Many

of the atrophic cells are not quiescent and possess a phenotype that is

intermediate between basal and luminal cells. Intermediate epithelial

cells have been postulated to be the targets of neoplastic transformation

in the prostate (6). Additionally, PIA cells show elevated levels of GSTP1,

glutathione S transferase alpha (GSTA1) and COX-2 in many cells, suggesting

that these cells are responding to increased oxidant/nitrosative/electrophilic

stress. Many of the molecular and genetic changes seen in HGPIN and cancer

have also been documented in PIA (7).

In

morphological studies, it has been observed frequent merging of areas

of focal atrophy directly with high grade PIN (7). It has been observed

these atrophic lesions near early carcinoma lesions, at times with direct

merging between atrophic epithelium in PIA and adenocarcinoma (7). Some

of such changes could be called atrophic HGPIN.

Malignancy-associated

changes (Putative preneoplastic markers with minimal or no morphological

changes) - Malignancy-associated changes refer to molecular abnormalities

in the epithelial cells that are not usually distinguishable by routine

light microscopic examination.

Scant

data are available in the prostate. Normal-looking epithelium in prostates

with adenocarcinoma may show some molecular abnormalities in GSTP- I and

telomerase that are similar to those in cancer (2). These observations

are related to the so-called “enzyme-altered foci” as putative

preneoplastic markers (8,9). According to Dr TG Pretlow and co-workers,

the most abundant of these lesions with molecular alterations show minimal

or no morphological changes (8). Changes occur also in the stroma. Montironi

et al (10) have shown that the degree of vascularization in normal-looking

prostate tissue from total prostatectomies performed because of a preoperative

diagnosis of PCa is close to that of LGPIN.

The

transition from normal-looking epithelium to prostate cancer without an

intermediate morphological stage identifiable as HGPIN was considered

possible (8). This raises the question of the existence of PIN without

morphological changes as a precursor of some well-differentiated adenocarcinomas

of the transition zone.

Atypical

adenomatous hyperplasia – AAH (Adenosis) - Is characterized by a

circumscribed proliferation of closely packed small glands that tends

to merge with the surrounding, histologically benign glands (11). AAH

has been considered a premalignant lesion of the transition zone. A direct

transition from AAH to cancer, as it has been observed between HGPIN and

cancer, has not been documented. The link between cancer and AAH is probably

an epiphenomenon and that the data are insufficient to conclude that AAH

is a premalignant lesion.

REFERENCES

- Montironi R, Mazzucchelli R, Algaba F, Lopez-Beltran A: Morphological identification of the patterns of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and their significance. J Clin Pathol. 2000; 53: 655-65.

- Billis A, Freitas LLL, Magna LA, Ferreira U: Inflammatory Atrophy on Prostate Needle Biopsies: Is There Topographic Relationship to Cancer?” Int Braz J Urol. 2007 (present work).

- Bostwick DG, Brawer MK: Prostatic intra-epithelial neoplasia and early invasion in prostate cancer. Cancer. 1987; 59: 788-94.

- Putzi MJ, De Marzo AM: Morphologic transitions between proliferative inflammatory atrophy and high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Urology, 2000; 56:828-32.

- De Marzo AM, Marchi VL, Epstein JI, Nelson WG: Proliferative inflammatory atrophy of the prostate: implications for prostatic carcinogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1999; 155: 1985-92.

- van Leenders G, Dijkman H, Hulsbergen-van de Kaa C, Ruiter D, Schalken J: Demonstration of intermediate cells during human prostate epithelial differentiation in situ and in vitro using triple-staining confocal scanning microscopy. Lab Invest. 2000; 80: 1251-8.

- De Marzo AM, DeWeese TL, Platz EA, Meeker AK, Nakayama M, Epstein JI, Isaacs WB, Nelson WG: Pathological and molecular mechanisms of prostate carcinogenesis: implications for diagnosis, detection, prevention, and treatment. J Cell Biochem. 2004; 91: 459-77.

- Montironi R, Thompson D, Bartels PH (1999) Premalignant Lesions of the Prostate. In: Lowe DG, Underwood JCE (Eds), Recent Advances in Histopathology. Orlando, Elsevier, 1999; pp. 147-72.

- Pretlow TG, Nagabhushan M, Pretlow TP: Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and other changes during promotion and progression. Path Res Pract. 1995; 191: 842-9.

- Montironi R, Galluzzi CM, Diamanti L, Taborro R, Scarpelli M, Pisani E: Prostatic intra-epithelial neoplasia. Qualitative and quantitative analyses of the blood capillary architecture thin tissue sections. Path Res Pract. 1993; 189: 542-8.

- Cheng L, Shan A, Cheville JC, Qian J, Bostwick DG: Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia of the prostate: a premalignant lesion? Cancer Res. 1998; 58: 389-91.

Dr. Rodolfo

Montironi

Polytechnic University of the Marche Region

Institute of Pathological Anatomy

School of Medicine, United Hospitals

Ancona, Italy

E-mail: r.montironi@univpm.it

Dr. Liang

Cheng

Dept of Pathology & Lab Medicine

Indiana University School of Medicine

Indianapolis, IN, 46202, USA

E-mail: liang_cheng@yahoo.com

EDITORIAL COMMENT

A hypothesis for prostate carcinogenesis proposes that injury to the prostate from a variety of causes leads to chronic inflammation and proliferative inflammatory atrophy (PIA) which may be a risk factor for prostate cancer. Prostatic glandular atrophy can be diffuse or focal with diffuse atrophy resulting from androgen deprivation. PIA is a type of focal atrophy that occurs in the absence of androgen deprivation and occurs in small or large foci, most commonly in the peripheral zone. Recognized morphological types of PIA include simple atrophy and postatrophic hyperplasia in which chronic inflammation as well as increased proliferative activity has been demonstrated. It is unknown whether the other types of focal atrophy, including simple atrophy with cyst formation and partial atrophy have increased cellular proliferation. Therefore, these lesions are currently not considered PIA. A variety of other carcinomas including those in the liver, stomach, large bowel and urinary bladder appear to be related to long-standing chronic inflammation and proliferation. Prostate cancer and its precursor, high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) have has been linked with PIA lesions through topographical and morphological associations. De Marzo et al. (1) have shown frequent morphological transitions between HGPIN and PIA suggesting that PIA may be a high-risk lesion for prostate cancer through HGPIN. Although topographical and morphological associations alone are not proofs of a cancer-causing role for PIA lesions, these support a model of prostatic carcinogenesis in proliferative epithelium in chronic inflammation. The authors studied needle core biopsies of patients with prostate cancer and did not show a topographical relationship of inflammatory atrophy to adenocarcinoma. Other studies have shown similar results with inflammatory atrophy found to be a very common lesion. These findings, while not supporting this model of prostate carcinogenesis, do not rule out this association and ultimately experimental animal studies, epidemiological studies and molecular pathological approaches are needed to clarify this hypothesis.

REFERENCE

1. Putzi MJ, De Marzo AM: Morphologic transitions between proliferative inflammatory atrophy and high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Urology. 2000; 56: 828-32.

Dr. H. Samaratunga

Department of Anatomical Pathology

Sullivan Nicolaides Pathology

Royal Brisbane Hospital

University of Queensland

Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

E-mail: hema_samaratunga@snp.com.au