MONTI’S

PROCEDURE AS AN ALTERNATIVE TECHNIQUE IN COMPLEX URETHRAL DISTRACTION

DEFECT

(

Download pdf )

doi: 10.1590/S1677-55382010000300008

JALIL HOSSEINI, ALI KAVIANI, MOHAMMAD M. MAZLOOMFARD, ALI R. GOLSHAN

Reconstructive Urology, Shohada Tajrish Hospital, Shaheed Beheshti Medical Sciences University, Tehran, Iran

ABSTRACT

Purpose:

Pelvic fracture urethral distraction defect is usually managed by the

end to end anastomotic urethroplasty. Surgical repair of those patients

with post-traumatic complex posterior urethral defects, who have undergone

failed previous surgical treatments, remains one of the most challenging

problems in urology. Appendix urinary diversion could be used in such

cases. However, the appendix tissue is not always usable. We report our

experience on management of patients with long urethral defect with history

of one or more failed urethroplasties by Monti channel urinary diversion.

Materials and Methods: From 2001 to 2007,

we evaluated data from 8 male patients aged 28 to 76 years (mean age 42.5)

in whom the Monti technique was performed. All cases had history of posterior

urethral defect with one or more failed procedures for urethral reconstruction

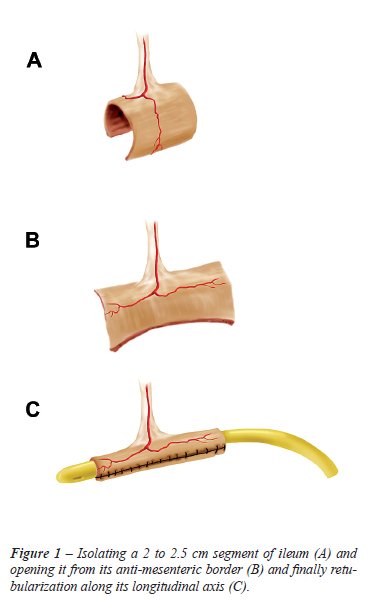

including urethroplasty. A 2 to 2.5 cm segment of ileum, which had a suitable

blood supply, was cut. After the re-anastomosis of the ileum, we closed

the opened ileum transversely surrounding a 14-16 Fr urethral catheter

using running Vicryl sutures. The newly built tube was used as an appendix

during diversion.

Results: All patients performed catheterization

through the conduit without difficulty and stomal stenosis. Mild stomal

incontinence occurred in one patient in the supine position who became

continent after adjustment of the catheterization intervals. There was

no dehiscence, necrosis or perforation of the tube.

Conclusion: Based on our data, Monti’s

procedure seems to be a valuable technique in patients with very long

complicated urethral defect who cannot be managed with routine urethroplastic

techniques.

Key

words: urethra; urethral stricture; urinary diversion

Int Braz J Urol. 2010; 36: 317-26

INTRODUCTION

Strictures and defects of the posterior urethra in men is one of the most significant clinical complications concerning urologists (1). Posterior urethral injuries in pelvic fracture were estimated at 5 to 10 percent in previous studies (2). Anastomosis is usually performed for defects of the posterior urethra. However, in some cases the urethral defect is so long that it cannot be negotiated with vigorous releasing of urethra from surrounding tissue, inferior pubectomy and even re-routing maneuvers (1,3). Based on the location and length of the stricture, various techniques have been used in such cases including onlay repairs, stricture excision with augmented anastomosis, a tubularized flap of sigmoid colon, and free or vascularized skin flap, etc. However, many complications have been related to these techniques (4,5). Other options such as perineostomy or suprapubic tube could also be used as salvage procedure (6,7). Application of appendix tissue for the creation of a catheterizable stoma remains a useful technique in patients with more severe urethral injuries (8); although, the appendix is not always usable (9). The appendix may be absent or insufficient in length or quality. It may have a precarious blood supply, a short mesentery or histopathologic changes, such as chronic inflammation or fibrous lumen obstruction (9). Regarding these situations, the technique which was originally proposed by Monti et al. is a good alternative method when the appendix is unavailable, atretic or used concurrently with another procedure (10). We reviewed our results regarding this surgical technique in eligible patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From 2001 to 2007, we evaluated data from 8 male patients aged 28 to 76 years (mean age 42.5) on whom we performed the Monti technique at Tajrish Hospital, Tehran, Iran. All patients had a previous history of urethral distraction defect and a history of at least one failed urethroplasty and a defect longer than 10 centimeters in distal prostatic, membranous, bulbar and some part of penile urethra. Due to a very long urethral defect that could not be repaired by urethroplasty, a Monti urinary diversion was performed in the patients. Informed consents were signed by all enrolled patients. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital.

Surgical Technique

After isolating a 2 to 2.5 cm segment of ileum, with a suitable blood supply, we opened the ileal segment along its anti-mesenteric border by Metzenbaum scissors, and then closed the opened ileum transversely surrounding a 14-16 Fr urethral catheter using running Vicryl sutures (Figure-1). The length of small intestine which was resected did not determine the length of the newly built tube, but rather its diameter. Therefore, using 1 or 2 cm segment of the small intestine, leads to a narrow and wide tube, respectively. The 15 cm of terminal ileum was not routinely used for this type of procedure.

The double tube technique was used in obese patients. In this procedure,

a 5 cm segment of the ileum was isolated, cut into two halves and tabularized,

each one exactly as described previously. The two segments were anastomosed

to each other using an interrupted 3-0 Vicryl sutures to build a single

tube.

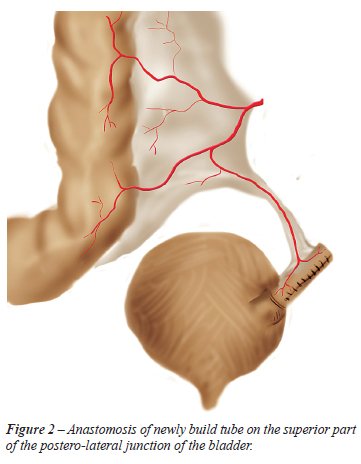

After the reconstruction of a new appendix, anastomosis was performed

on the superior part of the postero-lateral junction of the bladder. The

Mitrofanoff principle was not used; the bladder wall was opened and anastomosed

to the new appendix using 3-0 Vicryl sutures (Figure-2). The stoma was

made at level which was located proximally relative to the bladder in

order that gravity can help the patient’s continence. A cystostomy

tube was performed for all the patients to increase the safety measures.

All patients were discharged 5-6 days postoperatively as soon as they

could tolerate solid food. The diversion catheter was removed 3 weeks

post-operatively. All patients were put on a clean intermittent catheterization

(CIC) regimen using a 14 or 16 Fr nelaton catheter every 3 hours. Presence

of urinary leakage during the interval was considered as the patient being

incontinent. The cystostomy tube was removed 7 days later, if there was

no difficulty in catheterization.

Demographic characteristics, distraction defect length, previous surgical

procedures, time of operation and hospitalization, estimated blood loss,

and complications such as peri-operative bleeding (need for blood transfusion),

adjacent organ damage, hematoma and wound infection were recorded.

The patients were regularly followed-up at 3,6,18 and 24 months postoperatively,

with special attention to any problems with catheterization and incontinence.

Follow-up plan consisted of physical examination including stoma evaluation;

upper urinary tract sonography and determining of post catheterization

urine residue; and serum creatinine level and catheter size assessment.

RESULTS

Eight patients were included in this study. Causes of urethral injury and pelvic fracture consisted of 4 motor vehicle accidents, 2 falls and one shot gun injury. The time interval between injury and Monti procedure ranged from 23 to 48 months (mean 31.4). Patients’ general data, previous operative procedures and outcome are listed in Table-1. Sonographic assessment of upper urinary tract did not reveal any pathologic findings, and mean serum creatinine level was 1.3 mg/dL (0.6 to 1.7) pre-operatively. The patients did not have an available or suitable appendix (Table-2).

Seven patients underwent single tube technique and in the obese patient,

double tube procedure was performed. Mean surgical time was 4.5 hours

(range 3 to 8) with defect lengths of 11.75 cm (10 to 14). Average estimated

blood loss was around 350 cc (ranged 200 to 800). There was no need for

blood transfusion or adjacent organ damage. All patients were discharged

5-6 days post operatively.

Follow-up ranged from 24 to 30 months (mean 25.75). Immediate post-operative

complications such as hematoma and wound infection were not detected.

All patients performed catheterization through the conduit without difficulty

every 3 hours. Catheter size ranged from 14 to 16 Fr. None of the 8 patients

had stomal stenosis during the follow-up period. Mild stomal incontinence

occurred in one patient in the supine position which became continent

after some adjustments of the catheterization intervals. This patient

had previous history of urethroplasty and failed appendicovesicostomy

at another surgical center. There was no dehiscence, necrosis, or perforation

of the tube during the follow-up period.

Also, there was no significant difference between pre-operative and post-operative

serum creatinine levels and upper tract sonographic data, which were evaluated

at the time of scheduled surgery as well as 3,6,18 and 24 months post-operatively.

COMMENTS

In 1989

Turner-Warwick explained some features of complex urethral distraction

defect including long urethral gap between tow ends (11). In severe urethral

injuries with long strictures or urethral defects especially in patients

who have undergone failed previous surgical treatments, various methods

have been used to obtain urethral continuity (4). Surgical options are

offered based on the location and length of the stricture. One-stage vascularized

scrotal skin flap urethroplasty and a two-stage Johanson’s procedure

were two surgical examples for treatment of complex lengthy urethral strictures

(12). Skin flap urethroplasty can lead to some complications such as recurrent

stricture, troublesome post void dribbling, and diverticulum formation

(4). In the last decade, buccal mucosa urethroplasty has increased in

popularity because of its feasibility, good functional outcome, and low

morbidity at the reconstructed urethra. However, treatment of long, complicated

urethral strictures by buccal mucosal graft may not be useful, because

of limited material (4,5).

Recently some investigators have described novel surgical techniques for

male long segment urethral defect. In 2006, Yue-Min Xu et al. reported

a new technique for treatment of men with long urethral defect after pelvic

trauma using the intact and pedicled pendulous urethra to replace the

bulbar and membranous urethra, followed by reconstruction of the anterior

urethra (12). Buyukunal et al. developed a new treatment modality in a

rabbit model, using appendix interposition for substitution of severe

posterior urethral injuries (13). This technique was also used by Aggarwal

et al. in recurrent urethral strictures (14).

Other options such as perineostomy or suprapubic tube could also be used

as a salvage procedure in such situations. Suprapubic tube is a safe and

simple treatment of acute or chronic urinary retention but has some complications

especially in long-term such as infection, difficulty in changing of catheter

and risk of malignancy (6). Barbagli et al. evaluated the clinical outcome

of patients with complex urethral pathology who were treated with perineal

urethrostomy. These authors showed that success rate of urethroplasty

after perineal urethrostomy is lower in younger patients with traumatic

urethral stricture (7).

In 1980, Mitrofanoff first described the use of the appendix as a continent

urinary stoma (15). The major indications for constructing a urinary diversion

are patients with a low leak-point pressure and neurogenic bladder, an

unreconstructable bladder (e.g. exstrophy), an unreconstructable urethral

disease or the inability to catheterize the urethra in a neurogenic bladder

(8).

With this concern, we use a urinary diversion in patients with unreconstructable

long urethral defect, in order to empty their bladder. As Monti et al.

described in 1997 (10), a continent catheterizable conduit using short

segments of the small intestine was used for this aim. The use of this

technique allows us to obtain some benefits. Only 2 to 2.5 cm segment

of the ileum is required. The caliber of such a tube allows catheterization

with a 16F to 18F catheter, and the mucosal folds of the ileum are aligned

with its longitudinal axis. These tubes have an abundant supply of blood

and are able to be used anywhere inside the abdomen (9,10).

It is important to note that the length of the segment can be adjusted

by using a double tube or using a section of the large bowel, allowing

application of this technique in adults or obese patients (9). A 2.0-2.5

cm segment of bowel will usually result in a tube of 6-7 cm in length,

when re-tubularized transversely. If a longer channel is needed, two consecutive

segments can be cut, and anastomosed together to form a tube twice as

long but with mesentery only in the central portion of the tube. In our

study, one patient was candidate for the double tube technique. No stenosis

or incontinence occurred during his follow-up.

One of the best characteristics provided by Monti’s procedure is

urinary continence. In the series with longer follow-up periods, continence

maintenance is always greater than 90% and shows no considerable changes

with time (16,17). Narayanaswamy et al. reported their results with 94

Mitrofanoff procedures, of which 25 were Monti channels. Overall 23 of

25 patients were successfully catheterized at the time of the report and

only 3 of 25 had stomal leakage (18). In another large series Castellan

et al. reported a comparison among different types of channels for urinary

and fecal incontinence, including 45 Monti urinary channels, with a mean

follow-up of 38 months. Four of these channels were double Monti channels,

while the others were single Monti channels. Channel replacement was performed

in three patients (7%) due to complete fibrosis, and 3 cases (7%) had

stomal incontinence (16).

We did not use the Mitrofanoff principle to create an anti-incontinent

submucosal tunnel. Only anastomosis was performed on the superior part

of the postero-lateral junction of the bladder. Yang et al. (19) evaluated

the pressure profile of the channel tube, and detected two high-pressure

zones: one in the sub mucosal tunnel and the other at the point at which

the muscle layer of the abdominal wall is crossed. These data suggest

that the muscle layer of the abdominal wall is a major factor in preserving

of continence (9).

Our study shows that Monti’s procedure, even without the use of

the Mitrofanoff principle, is a reliable technique with low incontinence

and stricture rate. Obviously, we are not proposing that the Monti’s

procedure be the definitive treatment for complicated posterior urethral

injuries. Moreover, it can be performed in patients with very long urethral

stricture that cannot be corrected with the urethroplastic techniques,

and who also do not have a suitable appendix for appendix diversion techniques.

However, evaluation of patient’s satisfaction and the choice of

eligible cases need more investigations with larger number of patients.

CONCLUSION

Based on our data, Monti’s procedure is a valuable technique in patients with very long complicated urethral defect who lack a suitable appendix for appendicovesicostomy technique.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Hosseini J, Tavakkoli Tabassi K: Surgical repair of posterior urethral defects: review of literature and presentation of experiences. Urol J. 2008; 5: 215-22.

- Cass AS, Godec CJ: Urethral injury due to external trauma. Urology. 1978; 11: 607-11.

- Andrich DE, Mundy AR: What is the best technique for urethroplasty? Eur Urol. 2008; 54: 1031-41.

- Xu YM, Qiao Y, Sa YL, Wu DL, Zhang XR, Zhang J, et al.: Substitution urethroplasty of complex and long-segment urethral strictures: a rationale for procedure selection. Eur Urol. 2007; 51: 1093-8; discussion 1098-9.

- Barbagli G, Lazzeri M: Surgical treatment of anterior urethral stricture diseases: brief overview. Int Braz J Urol. 2007; 33: 461-9.

- Scorer CG: The suprapubic catheter; a method of treating urinary retention. Lancet. 1953; 265: 1222-5.

- Barbagli G, De Angelis M, Romano G, Lazzeri M: Clinical outcome and quality of life assessment in patients treated with perineal urethrostomy for anterior urethral stricture disease. J Urol. 2009; 182: 548-57.

- Freitas Filho LG, Carnevale J, Melo Filho AR, Vicente NC, Heinisch AC, Martins JL: Posterior urethral injuries and the Mitrofanoff principle in children. BJU Int. 2003; 91: 402-5.

- Monti PR, de Carvalho JR, Arap S: The Monti procedure: applications and complications. Urology. 2000; 55: 616-21.

- Monti PR, Lara RC, Dutra MA, de Carvalho JR: New techniques for construction of efferent conduits based on the Mitrofanoff principle. Urology. 1997; 49: 112-5.

- Turner-Warwick R: Prevention of complications resulting from pelvic fracture urethral injuries--and from their surgical management. Urol Clin North Am. 1989; 16: 335-58.

- Wu DL, Jin SB, Zhang J, Chen Y, Jin CR, Xu YM: Staged pendulous-prostatic anastomotic urethroplasty followed by reconstruction of the anterior urethra: an effective treatment for long-segment bulbar and membranous urethral stricture. Eur Urol. 2007; 51: 504-10; discussion 510-11.

- Büyükünal SN, Cerrah A, Dervisoglu S: Appendix interposition in the treatment of severe posterior urethral injuries. J Urol. 1995; 154: 840-3.

- Aggarwal SK, Goel D, Gupta CR, Ghosh S, Ojha H: The use of pedicled appendix graft for substitution of urethra in recurrent urethral stricture. J Pediatr Surg. 2002; 37: 246-50.

- Mitrofanoff P: Cystostomie continente trans-appendiculiaire dans le traitement des vessies neurologiques. Chir Pediatr. 1980; 21: 297-305.

- Castellan MA, Gosalbez R Jr, Labbie A, Monti PR: Clinical applications of the Monti procedure as a continent catheterizable stoma. Urology. 1999; 54: 152-6.

- Leslie JA, Dussinger AM, Meldrum KK: Creation of continence mechanisms (Mitrofanoff) without appendix: the Monti and spiral Monti procedures. Urol Oncol. 2007; 25: 148-53.

- Narayanaswamy B, Wilcox DT, Cuckow PM, Duffy PG, Ransley PG: The Yang-Monti ileovesicostomy: a problematic channel? BJU Int. 2001; 87: 861-5.

- Yang WH: Yang needle tunneling technique in creating antireflux and continent mechanisms. J Urol. 1993; 150: 830-4.

____________________

Accepted

after revision:

November 3, 2009

_______________________

Correspondence

address:

Dr. Mohammad

Mohsen Mazloomfard

Shohada Tajrish Hospital

Shaheed Beheshti Medical Sciences University

Tehran, Iran

Fax: + 98 21 8852-6901

E-mail: mazloomfard@yahoo.com

EDITORIAL COMMENT

The authors report their experience on the management of eight patients with long urethral defects already submitted to at least one unsuccessful urethroplasty. All of them received continent cutaneous urinary diversion using as efferent catheterizable conduit transversely tubularized ileal segments with direct implantation into the bladder wall without antireflux technique. After two years of minimum follow up all subjects were continent with easy catheterization. The ileal tube was created to replace the appendix when unavailable to construct a urinary diversion based on the Mitrofanoff principle. Until that the proposed technical alternatives (around 20) showed clearly inferior results compared to the appendix technique and were based on the use of ureteral segments, longitudinally tapered ileal segments, gastric tubes, tubularized cecum flaps, fallopian tube, skin tubes (preputial penile or clitoral skin flaps, labia minora flaps), vas deferens, tubularized bladder flap, Meckel’s diverticulum, hipogastric artery segment, human umbilical vein, rectus abdominis muscle, aponeurosis flap. The long term follow up of ileal tube technique application provided equivalent results to those of the appendix related to function, durability and low complications index (1,2). For the tube construction, some technical points matter. The tube made from 2.5 cm isolated segment allows 14F to 16F catheters inside and the measurement should be performed with the bowel at rest, without stretching it. The tubularization is done with running suture of Vicryl 3-0 in adults and 4-0 in children and preceded by resection of lateral mucosal excess of the open intestinal plate. In the case of double tube, the suture between the plates should be done with simple interrupted stitch, which makes the tubularization easier. You can also use the double spiral tube, as proposed by Casale (3). The passage of the tube to the skin should be straight and as short as possible. Very long tubes evolve with greater difficulty in catheterization. The reservoir must be fixed to the abdominal wall with vicryl 3-0 interrupted stitch to stabilize the structure. The stoma can be done in a simple way or with skin flaps interposition. It is noteworthy the author’s option for direct implantation of the tube into the bladder wall trusting just in the resistance offered by the abdominal muscle layer when the tube pass through it. Since the Mitrofanoff’s pioneer publication in 1980 (reference 15) there were rare descriptions of direct implantation of the conduit into the reservoir without antireflux technique and with short periods of continence. Yang himself quoted by the authors (reference 19 in the article) utilized the antireflux technique in his unique case with ileal tube and interprets literally the pressure profile study of the tube: “The results show that although there are 2 high pressure profile zones for the continent ileal tube, the skeletal muscle pressure zone has a lesser role in the continence mechanism than the submucosal portion of the ileal tube”. Stress tests show an equal increased pressure inside the reservoir and in the antireflux tunnel but not in the skeletal muscle zone. This conclusion is the current stand-point and it seems risky to dismiss the use of an antireflux technique mainly in cases in which the tube implantation was done into the bladder wall, a structure that offers the best results among the available options. Long term studies show that the continent cutaneous urinary diversion made by the Mitrofanoff technique with appendix or reconfigured ileal tube offers consistent and lasting results besides the use of technical principles of easier execution already widely known and used in Urology.

REFERENCES

- Lemelle JL, Simo AK, Schmitt M: Comparative study of the Yang-Monti channel and appendix for continent diversion in the Mitrofanoff and Malone principles. J Urol. 2004; 172: 1907-10.

- Cain MP, Dussinger AM, Gitlin J, Casale AJ, Kaefer M, Meldrum K, et al.: Updated experience with the Monti catheterizable channel. Urology. 2008; 72: 782-5.

- Casale AJ: A long continent ileovesicostomy using a single piece of bowel. J Urol. 1999; 162: 1743-5.

Dr. Paulo

R. Monti

Section of Urology

Federal University of Minas Triangle

Uberaba, Minas Gerais, Brazil

E-mail: montipr@zaz.com.br

EDITORIAL COMMENT

Traumatic posterior urethral strictures (better defined as “pelvic fracture related urethral injuries”) as well as non-traumatic posterior strictures are rare conditions (1,2). As mentioned by the authors, most of these strictures can be managed by anastomotic repair. However, reports on “what to do” after failed urethroplasty are very scarce. The Monti-procedure was first described in 1997 (3) in an animal (dog) model and quickly found clinical applications as a continent catheterizable stoma in adult and paediatric patients (4), in case the appendix could not been used. This paper is the first to describe this technique for posterior urethral strictures after failed urethral reconstruction. The major importance of this paper is that it shows the feasibility of the procedure in these situations. Although it is explained in the text, the title is somewhat misleading. Monti’s procedure must not be regarded as an alternative to other procedures (such as anastomotic repair, substitution urethroplasty, perineostomy) in complex urethral distraction defects. One or even more attempts to restore urethral continuity must always be performed for these often young patients. If these attempts failed however, a strategy that abandons the urethral outlet can be proposed. For this reason, I prefer the term “salvage procedure” rather than the term “an alternative technique” for the Monti’s procedure in these patients. The authors did not apply the Mitrofanoff principle for implantation at the bladder. One patient out of 8 suffered from stomal incontinence. The authors state that this technique has thus a low continence rate. However, this conclusion is drawn on a small number of patients. Unless larger series can prove the opposite, there is at the present no reason to abandon the Mitrofanoff principle for prevention of stomal incontinence. Patients must also be informed about the long-term complications related to the Monti’s procedure difficult catheterisation, stomal stenosis and incontinence and it has been reported that 23-27.5% will need revision surgery at the Monti’s tube (5,6). There is no reason to assume that these complication and revision rate will be different in patients with traumatic urethral distraction defects.

REFERENCES

- Lumen N, Hoebeke P, Troyer BD, Ysebaert B, Oosterlinck W: Perineal anastomotic urethroplasty for posttraumatic urethral stricture with or without previous urethral manipulations: a review of 61 cases with long-term followup. J Urol. 2009; 181: 1196-200.

- Lumen N, Oosterlinck W: Challenging non-traumatic posterior urethral strictures treated with urethroplasty: a preliminary report. Int Braz J Urol. 2009; 35: 442-9.

- Monti PR, Lara RC, Dutra MA, de Carvalho JR: New techniques for construction of efferent conduits based on the Mitrofanoff principle. Urology. 1997; 49: 112-5.

- Castellan MA, Gosalbez R Jr, Labbie A, Monti PR: Clinical applications of the Monti procedure as a continent catheterizable stoma. Urology. 1999; 54: 152-6.

- Leslie JA, Dussinger AM, Meldrum KK: Creation of continence mechanisms (Mitrofanoff) without appendix: the Monti and spiral Monti procedures. Urol Oncol. 2007; 25: 148-53.

- Leslie JA, Cain MP, Kaefer M, Meldrum KK, Dussinger AM, Rink RC, et al.: A comparison of the Monti and Casale (spiral Monti) procedures. J Urol. 2007; 178: 1623-7; discussion 1627.

Dr. Nicolaas

Lumen

Department of Urology

Ghent University Hospital

Ghent, Belgium

E-mail: nicolaas.lumen@ugent.be

EDITORIAL COMMENT

In his commentary,

recently, Barbagli underlined that the management of posterior urethral

strictures, in patients after pelvic fracture urethral distraction defects

(PFUDD), has evolved over time (1). Forty, thirty years ago, in the ‘70s

and the ‘80s, the transpubic urethroplasty was considered the gold

standard in the majority of adults and children suffering from PFUDD.

Since ‘90s, thank to Webster and Ramon’s work, an elaborated

perineal approach to the posterior urethra was suggested (2). It used

ancillary maneuvers, such as separation of the corporeal body, inferior

pubectomy and retrocrural urethral rerouting, in order to reduce the gap

between the bulbar urethra and the prostatic apex, to remove scar tissue

and to perform a tension-free anastomosis.

The management of failed posterior urethroplasty after PFUDD remains challenging

and its surgery demanding. In this issue of International Brazil Journal

of Urology, Hosseini et al. reported their experience on the treatment

of adult patients with complex urethral defect after one or more failed

posterior urethroplasties using the Monti channel urinary diversion. The

paper is worth reading as it reports data in adult population, although

the Monti procedure is generally used in children. The reader should be

aware that failed posterior urethroplasty, in adults, may require urinary

diversion just like in primary reconstructive surgery for children. Adults

and children are two different populations. In children, PFUDD may evolve

into complex urethral strictures because it involves a not-yet-developed

proximal urethra (prostatic tract and bladder neck) as well as rudimentary

gland and pubo-prostatic ligaments (3,4). Furthermore, prepubescent boys

may have insufficient vascular connections in the glans, which is smaller

than in adults, resulting in inadequate retrograde blood flow to the distally-based

bulbar urethral flap (as a result of bulbar urethral transection and full

mobilization). This compromises retrograde blood flow to the anastomotic

site may explain the lower success rate of anastomotic urethroplasty in

prepubescent boys compared to the adult population (5).

Recently, we compared the spectrum of posterior urethral strictures following

PFUDD in developing countries and in Western countries, in order to evaluate

if the differences in etiopathogenesis and early treatment of PUFDD might

influence the outcome (6). We found remarkable differences in pathogenesis

and early treatment of patients with PFUDD. In developing countries, the

majority of patients with PFUDD developed an obliterative complex posterior

stricture as a consequence of a more serious trauma and delayed primary

treatment, which was done by the general surgeon. Hosseini et al.’s

paper could confirm this suggestion and it pushes us to reflect upon the

following matter. Due to increasing migration rates, the urologists, working

in Western countries, will most likely once again encounter the forgotten

complicated posterior urethral strictures after PFUDD, in the migrants

who have been previously managed in their original country that may require

complex perineal/transpubic access or urinary diversion. The implications

are evident. Surgical training for urethral reconstruction surgery should

be done within international approved surgical training programs which

deal with complex, challenging and forgotten situations such those Hosseini

and colleagues described and treated in their work.

REFERENCES

- Barbagli G: History and evolution of transpubic urethroplasty: a lesson for young urologists in training. Eur Urol. 2007; 52: 1290-2.

- Webster GD, Ramon J: Repair of pelvic fracture posterior urethral defects using an elaborated perineal approach: experience with 74 cases. J Urol. 1991; 145: 744-8.

- Wu DL, Jin SB, Zhang J, Chen Y, Jin CR, Xu YM: Staged pendulous-prostatic anastomotic urethroplasty followed by reconstruction of the anterior urethra: an effective treatment for long-segment bulbar and membranous urethral stricture. Eur Urol. 2007; 51: 504-10; discussion 510-11.

- Chapple C, Barbagli G, Jordan G, Mundy AR, Rodrigues-Netto N, Pansadoro V, McAninch JW: Consensus statement on urethral trauma. BJU Int. 2004; 93: 1195-202.

- Flynn BJ, Delvecchio FC, Webster GD: Perineal repair of pelvic fracture urethral distraction defects: experience in 120 patients during the last 10 years. J Urol. 2003; 170: 1877-80.

- Kulkarni SB, Barbagli G, Kulkarni JS, Romano G, Lazzeri M: The Spectrum of Posterior Urethral Strictures Following Pelvic Fracture Urethral Distraction Defects (PFUDD) in Developing and Developed Countries, and Implications in the Choice of Surgical Technique. J. Urol. 2010; in press.

Dr. Massimo Lazzeri

Department of Urology

Santa Chiara Hospital

Florence, Italy

E-mail: lazzeri.m@tiscali.it

Dr. Guido

Barbagli

Center for Reconstructive Urethral Surgery

Arezzo, Italy