EXTRACORPOREAL

SHOCKWAVE LITHOTRIPSY VERSUS URETEROSCOPY FOR DISTAL URETERIC CALCULI:

EFFICACY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION

(

Download pdf )

IBRAHIM F. GHALAYINI, MOHAMMED A. AL-GHAZO, YOUSEF S. KHADER

School of Medicine, Jordan University of Science & Technology, King Abdullah University Hospital, Irbid, Jordan

ABSTRACT

Objective:

We compared the efficacy of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL)

and ureteroscopy (URS) for the treatment of distal ureteral calculi with

respect to patient satisfaction.

Materials and Methods: This is a prospective

study where a total of 212 patients with solitary, radiopaque distal ureteral

calculi were treated with ESWL (n = 92) using Dornier lithotriptor S (MedTech

Europe GmbH) or URS (n = 120). Patient and stone characteristics, treatment

parameters, clinical outcomes, and patient satisfaction were assessed

for each group.

Results: The 2 groups were comparable in

regard to patient age, sex, stone size, and side of treatment. The stone-free

status for ESWL and URS at 3 months was 81.5% and 97.5%, respectively

(p < 0.0001). In addition, 88% of patients who underwent ESWL versus

20% who underwent URS were discharged home the day of procedure. Minor

complications occurred in 3.3% and 8.3% of the ESWL and URS groups, respectively

(p = 0.127). No ureteral perforation or stricture occurred in the URS

group. Postoperative flank pain and dysuria were more severe in the URS

than ESWL group, although the differences were not statistically significant

(p = 0.16). Patient satisfaction was high for both groups, including 94%

for URS and 80% for ESWL (p = 0.002).

Conclusions: URS is more effective than

ESWL for the treatment of distal ureteral calculi. ESWL was more often

performed on an outpatient basis, and showed a trend towards less flank

pain and dysuria, fewer complications and quicker convalescence. Patient

satisfaction was significantly higher for URS according to the questionnaire

used in this study.

Key

words: ureteral calculi; ureteroscopy; extracorporeal shockwave

lithotripsy

Int Braz J Urol. 2006; 32: 656-67

INTRODUCTION

Urinary

lithiasis can cause a greater or lesser degree of obstruction of the lower

ureter, depending on the size of the calculus, urothelial edema and the

degree of impaction, requiring instrumental treatment, sometimes as an

urgent procedure. In the past 25 years, the treatment of these calculi

has evolved from ureterolithotomy to ureterorenoscopy URS (1), extracorporeal

shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) (2), and endoscopic lithotripsy (3,4).

Advances in the design of the ureteroscope

and ongoing development in ESWL have greatly impacted the management of

ureteric stones (5). The indications for ureteroscopic lithotripsy have

increased with smaller semi-rigid ureteroscopes and reliable laser technology

and the production of more robust flexible instruments has further expanded

the indications for endoscopic intervention. Despite the definite success

of endourological stone treatment, ongoing questions about optimum management

remain debated among urologists.

ESWL and URS are currently accepted treatment

modalities for distal ureteral calculi. Some authors (6,7) favor ESWL

while others (8-10) prefer URS. For both treatment modalities stone-free

rates of more than 90% have been reported (7,9,10).

The American Urological Association Ureteral

Stones Clinical Guidelines Panel has found both to be acceptable treatment

options for patients, based on the stone-free results, morbidity, and

retreatment rates for each respective therapy. However, costs and patient

satisfaction or preference were not addressed (11).

We aim to compare herein the efficacy and

safety of ESWL and URS for distal ureteral calculi with respect to patient

satisfaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A

total of 212 patients undergoing therapy for distal ureteral calculi between

January 2001 and December 2004 were entered into the study. Patients presented

with radiodense ureteral stones distal to the bony pelvis on excretory

urogram or computed tomography (CT) which had not passed spontaneously

within 3 weeks. Patients were included in the study only if the intervention,

either ESWL or URS, was the primary modality and there was a minimum follow-up

period of 3 months. Patients for whom either therapeutic modality was

contraindicated because of pregnancy, urinary tract infection, coagulation

disorders or previous ureteral reimplantation were excluded from the study.

After defining the indications of treatment,

the patients were made aware of both the modalities of treatment and their

probable complications. The need for anesthesia, stent, urethral manipulation,

possible complications, need for repeated follow up especially after ESWL,

and the cost factor involved, were explained to the patient. The patients

were then asked to choose the mode of treatment.

ESWL was performed using the Dornier lithotriptor

S (MedTech Europe GmbH). All patients were positioned prone and the calculi

were localized with fluoroscopic guidance. All patients were given sedatives

and analgesics and the level of shockwave energy was progressively stepped

up till satisfactory stone fragmentation within the patient’s comfort.

URS was performed with rigid 8F Wolf ureteroscope following dilatation

of ureteric orifice if needed. The stones were either extracted via basket

or forceps, or disintegrated with the Pneumatic lithotripsy lithotriptor.

Placement of a ureteral stent at the conclusion of the procedure was left

to the discretion of the treating surgeon. Upon completion of the procedure,

fluoroscopic imaging was performed to determine whether the ureter was

stone-free. All patients were administered prophylactic antibiotic.

Complete stone clearance was assessed at

three months follow up. Patients were followed-up to assess the success

rates and complications of the two procedures. The follow up schedule

was similar in both groups of patients. Plain x-rays were obtained 1,

2, 4 and 6 weeks after discharge and thereafter if residual fragments

persisted. Obstruction of the upper urinary tract was excluded from diagnosis

with the help of ultrasonography. In case of recurrent ureteral colic

or if calculi failed to pass within 6 weeks ureteroscopic stone removal

was performed. Treatment failure was based on the need for further surgical

intervention during follow-up or failure to become stone-free within 3

months (7). At initial follow-up, patients were given a questionnaire,

which we use for all patients with urolithiasis in our center based on

published data about the factors that influenced patient satisfaction

(7,9) (Table-1). Those with total score of 8 or less were considered satisfied

with the procedure. The efficiency quotient (EQ) was calculated using

the formula: Stone free (%) × 100/ (100 + retreatment rate (%) +

rate of auxiliary procedures (%)) (12).

Data were analyzed using Statistical Package

for Social Sciences (SPSS, version 11.5). Pearson’s chi-square,

student t-test, Mann-Whitney U test was used where appropriate and p <

0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

One

hundred and twenty patients were treated with URS (male/female: 85/35),

while 92 (male/female: 70/22) patients were treated by ESWL. Patient’s

age varied between 11 and 75 years, with maximum number of patients between

35 to 45 years of age. There were no significant differences in the mean

age, sex ratio and stone size in both groups (Table-2). For the extracorporeal

modality, i.e. ESWL, the mean stone size was 10.4 ± 5.3 mm (range

4 to 27) (Table-2). In this group, 90% received intravenous sedation and

10% general anesthesia. Majority of the patients (88%) had treatments

as an outpatient procedure but all patients needed frequent follow-up

visits. Only 4 patients (4.3%) required pre-ESWL double pigtail stents

for persistent ureteric colic not responding to conservative treatment.

A total of 92 patients required 115 sessions of lithotripsy with average

number of 3720 shock waves at 10-20 kV. Stone-free status at 1 month and

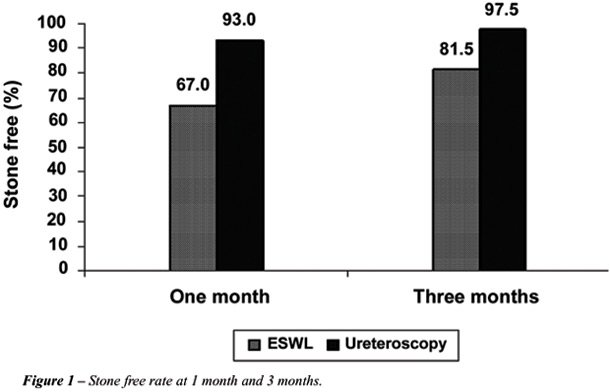

3 month were 67% (n = 62) and 81.5% (n = 75), respectively (Figure-1).

There were no major complications, although three patients (3.3%) developed

fever and infection. In total, 23 patients (25%) required more than one

session of ESWL for disintegration, whereas 17 patients (18.5%) where

ESWL failed were treated by URS for 16 cases and open ureterolithotomy

for one patient with a hard 27 mm stone (Table-3). Of these, there were

4 cases of “steinstrasse” (4%) after ESWL and only 2 were

treated conservatively; the other 2 required URS. EQ at 3 months was 57.

Considerable differences with regard to patient satisfaction were noted

with a mean score of 5.03 ± 3.08. Of the patients 74 (80%) were

satisfied and will recommend the procedure to the others while 18 (20%)

who required re-treatment or URS would opt for URS for recurrence (Table-3).

For the intracorporeal modality, i.e. URS

with pneumatic lithotripsy, the mean stone size was 9.2 ± 5.4 mm

(range, 4 to 27) (Table-2). In this group, 60% of patients had general

anesthesia, 25% local anesthesia and 15% intravenous sedation. The majority

of the patients had treatments as an inpatient procedure (80%) mainly

for ‘social’ reasons, like difficulty in transport. Some of

these were admitted for pain control, infection and stent-related symptoms

but all patients needed less frequent visits for follow-up than ESWL.

After URS, ureteric catheter or double J stent was kept in 41 patients

(34.2%) for 24 hours to 3 weeks. Of these, 12 patients (10%) required

postoperative double-J ureteric stenting due to high stone load. In 28

cases (23%), the calculi could be extracted without fragmentation (forceps

retrieval in 17 and basket retrieval in 11) and all other stones were

fragmented using the Pneumatic lithotripsy lithotriptor. Repeat URS was

however required in 8 patients (6.7%) after 4 weeks (Table-3). EQ at 3

months was 89. In these patients the initial attempt of URS failed due

to failure to adequately dilate the ureteric orifice in six and submucosal

dissection with false passage in two patients. Open surgery was required

for one of these patients who had a hard 25 mm stone. The proximal migration

of calculus occurred in 2 patients (1.7%) who were treated by ESWL. Mean

hospital stay in URS was two days. With respect to complications, there

were 6 cases (5%) of infection in addition to 2 cases of proximal stone

migration and 2 cases of submucosal dissection. No long-term complications,

such as ureteric stricture, were documented during the follow-up period.

Oral pain medication was used in 86% of the URS compared with 74% of ESWL

cases (p = 0.019), for a significantly longer duration (2.4 ± 1.5

versus 1.9 ± 1.5 days, respectively, p = 0.029). Follow-up was

significantly shorter for the URS group (4.2 ± 3.4 versus 5.8 ±

3.0 weeks, p = 0.0001) (Table-3). Stone-free status at 1 month and 3 months

were 93% and 97.5%, respectively (Figure-1). The mean satisfaction score

was 4.03 ± 2.08 which is significantly different from the ESWL

group (p = 0.043). Overall, 113 patients (94%) were completely satisfied

with the therapeutic modality chosen and will recommend it to the others

except for the 7 patients who required re-treatment or open surgery and

preferred to undergo ESWL for recurrence (Table-3).

COMMENTS

Ureteric

stones have a high probability of spontaneous clearance. Spontaneous passage

should be favored if possible (11,13). According to a meta-analysis by

the AUA Guidelines Panel, newly diagnosed stones with a diameter <

5 mm will pass in up to 98%, depending on the degree of obstruction, urothelial

edema and degree of impaction (11). With close controls and in absence

of risk factors like impaired renal function, pain, urinary tract infection

or fever, these stones can be followed safely until spontaneously cleared.

However, most authors recommend not exceeding 4-6 weeks, especially for

obstructive ureteric calculi (14,15). These data show that the success

rate is strongly influenced by the timing of therapeutic intervention

(9). The sooner therapy is initiated, the more stones that might have

passed spontaneously will be treated and, thus, false results in favor

of the chosen procedure will be obtained. In particular small stones have

a high spontaneous passage rate and so therapeutic intervention should

be delayed to allow clearance (9). For this reason treatment was delayed

in our study until 3 weeks after the diagnosis of a prevesical stone unless

earlier therapeutic intervention was mandatory because of recurrent colic.

Peschel et al. (9) have reported on the

differences that they have encountered in dealing with distal ureteral

calculi with both ESWL and URS (rigid or semi-rigid). URS was significantly

better in terms of shorter operative time, fluoroscopy time and time to

achieve a stone free status. The authors recommend URS as first-line treatment

for smaller stones (< 5 mm) that do not pass spontaneously.

In our series patient satisfaction was uniformly

high in both groups but only significantly higher for URS (94 %) compared

to shock wave lithotripsy (80%) (p = 0.002). Also, patient willingness

to undergo a repeated procedure of the same type favored URS. No true

validated instrument exists for comparing patient symptoms and satisfaction

with these different treatment options (16).

The efficacy of the treatment cannot be

only judged by the stone free rate but various other parameters like postoperative

symptoms, patient willingness to undergo a repeated procedure or to recommend

it and the time of return to normal activity. The satisfaction criteria

in this study were more extensive. In our series from the patient viewpoint

achieving a stone-free state as soon as possible is the ultimate goal

once the therapeutic approach has been chosen by most of the patients.

Patient satisfaction generally reflected

treatment success. When assessing the efficacy of treatment an important

consideration is the time it takes to achieve a stone free status. Peschel

et al. (9) also concluded that in this respect there are considerable

differences between ESWL and URS. Results of their patient assessment

clearly demonstrated how important it is to achieve a stone free state

early and even the patients who were free of symptoms said that the awareness

of residual stone fragments and fear of colic were an ever present source

of discomfort and restricted their ability to perform daily activities.

Therefore, most patients in their study were satisfied with URS but would

not be satisfied with ESWL. Pearle et al. (7) found no significant difference

in postoperative symptoms between the 2 treatment groups despite the presence

of a ureteral stent in virtually all patients who underwent URS but only

16% of the ESWL group. Their sample size may preclude statistical significance

but there was a definite trend towards fewer symptoms in regard to bladder

irritability with shock wave lithotripsy. The ESWL group used less pain

medication for a shorter period compared with the URS group, and patient

satisfaction slightly favored ESWL (7). They recommended ESWL with a HM3

lithotripter as first-line treatment for distal stones. In our series,

oral pain medication was used by 74% of the ESWL group compared to 86%

of the URS cases, (p = 0.019), and the duration of analgesic use was significantly

longer in the URS group (p = 0.029). Despite this our patients favored

URS because of the longer time to obtain a stone free status with the

ESWL in addition to the other parameters in the questionnaire. In this

respect our results are in agreement with those of Peschel et al. (9).

From a retrospective review of planned same-day

discharge after ureteroscopy in 114 patients, Wills and Burns (17) concluded

that ureteroscopy should be considered an outpatient procedure. They reported

a 24% immediate admission rate, with about half the admissions for “social”

reasons. The inclusion of social components within our routine assessment

minimizes admission required for social reasons. Our patients have difficulty

in transports as they live far away from the hospital.

Given the high success rates for both treatment

modalities in our study, treatment success must also consider secondary

outcome parameters, such as complications rates, patient satisfaction,

procedural efficacy and cost. Complication rates are low for the treatment

modalities. In neither the series of Pearle et al. (7) or Peschel et al.

(9) did ureteral perforation or stricture occur in either treatment group.

However, ureteral injury is an established, albeit rare, complication

of URS that has never been reported to occur with in situ shock wave lithotripsy.

Furthermore, complications associated with ESWL are generally mild and

related to fragment passage. In our series, although not reaching statistical

significance, an almost 3-fold increase in minor complications occurred

with URS compared to ESWL. Consequently, ESWL is a marginally safer modality

associated with few if any long-term sequelae.

However, the invasiveness of ureteroscopy

cannot be neglected. Before the emergence of modern techniques for stone

fragmentation and newer, better-designed ureteroscopes, complications

like ureteric perforation and avulsion were not uncommon. A comprehensive

review of acute endoscopic injuries reported in the literature from 1984

to 1992 identified 314 ureteric perforations that occurred in 5117 procedures

(6.1%) and complete ureteric avulsion in another 17 procedures, though

infrequent, were documented (0.3%) (18). Harmon et al. (19) observed a

decrease in overall complications from 20% to 12% during a 10-year period

which were attributed to smaller ureteroscopes and increased surgeon’s

experience. Schuster et al. (20) suggested a significant reduction in

ureteric perforation with a less operative time and postoperative complications

with the surgeon’s experience. Proximal migration of stones occurred

in 2 patients (1.7%), which is less than what had been reported. (21,22).

With the emergence of flexible ureteroscopes, migrated stones could be

retrieved with basket. However, these state-of-the-art ureteroscopes are

fragile and experience in our center is still limited. We still use semi-rigid

ureteroscopes for all ureteric calculi.

In our study, only 12 patients (10%) of

the URS group had a double-J ureteric stent inserted for high stone load

while 29 patients (24.2%) had ureteric catheters for 24 hours. This significantly

reduces the occurrence of colic, hematuria and other complications of

obstruction. In the majority of patients undergoing uncomplicated URS

for removal of distal ureteral calculi postoperative discomfort is modest,

lasts less than 2 days and is easily controlled with oral analgesics.

Stricture formation has not been identified. Hence, we do not believe

that routine placement of a ureteral stent following uncomplicated URS

for a distal ureteral calculus is necessary. Routine placement of ureteral

stent after ureteroscopic stone has been considered the standard of care

in most centers but Denstedt et al. (23) performed a prospective trial

of non-stented versus stented ureteroscopic lithotripsy, and concluded

that patients without a stent have significantly fewer symptoms in the

early post-operative period, while there were no differences in terms

of complications and stone free status. In addition it is also important

to notice that with ESWL, more follow-up visits to the clinic were required

until a stone-free state was achieved and at each visit, the patient was

exposed to radiation from plain radiography.

Some investigators concluded that prophylactic

antibiotic during ESWL are unnecessary in patients whose urine before

treatment was sterile (24), other studies showed that antibiotic prophylaxis

with several agents can reduce the rate of bacteriuria significantly (25).

Currently, many urologists routinely prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis

to reduce the potential risk.

On the other hand, an important disadvantage

of URS is that the procedure has to be performed under general or spinal

anesthesia as compared to ESWL, which uses intravenous analgesia. This

exposes the patient to the risks of anesthesia and makes it unfavorable

to patient with significant medical problems but there are some reports

on local anesthesia combined with intravenous sedation for URS (26,27).

From our series local anesthesia with intravenous sedation were sufficiently

effective and safe in our patients with good tolerance. The need for anesthesia

during ESWL depends largely on the energy source. While spark gap lithotripters

(HM-3, MFL 5000) are highly effective, they are also more painful for

the patient, whereas piezoelectric shock wave lithotripsy is associated

to the least pain yet low efficacy. We could not find difficulty in stone

localization under sedation with the Dornier Lithotripter S. We suggest

that the choice of treatment modality for ureteric stones will depend

on the patient since the expertise for both modalities are equally available.

Patient’s factors will include acceptance of invasive procedure,

physical health and preference for earlier stone-free status.

The American Urological Association (AUA)

Guidelines Panel (11) reported its recommendations for the treatment of

ureteric stones. Although this report was clear in its recommendations

of in situ shock wave lithotripsy for the treatment of small ureteral

calculi, it was less clear for the large (> 1 cm) upper ureteric stones.

Although ESWL, URS, percutaneous stone extraction and open surgery were

evaluated as different options; laparoscopic ureterolithotomy was not

mentioned. Indeed, the previously mentioned treatment options have rendered

open procedures a rarity in many hospitals (28). Open surgery was required

for two of our patients with hard large stones. Sharma et al. (29) reported

that open mini-access ureterolithotomy to be a safe and reliable minimally

invasive procedure; its role is mainly confined to salvage for failed

first-line stone treatments but in selected cases, where a poor outcome

can be predicted from other methods, it is an excellent first-line treatment.

Laparoscopy has the advantage of high probability of removing the entire

stone in one procedure, exactly like open surgery.

Success rates for shock wave lithotripsy

may differ according to the lithotriptor used. Average stone-free rate

for cumulative shock wave lithotripsy series in the literature using an

HM3 lithotriptor is slightly but consistently higher than that achieved

with many second and third generation lithotripters and may influence

the choice of treatment (30). It is important to stress that the results

with shock wave lithotripsy are truly machine specific and cannot be translated

to use with other lithotripters (31).

The Dornier Lithotripter S that we use,

proved in different series to be very effective in the treatment of renal

and ureteral calculi (32). Though this is not randomized prospective study,

matching the two groups in terms of age, sex and stone size and studying

consecutive patients managed by the same group of urologists minimize

patient selection bias.

In summary, ESWL offers minimal-invasiveness

but a higher risk of treatment failure compared to URS which reaches immediate

high stone free rates. ESWL is a marginally safer modality associated

with few if any long-term sequelae. Treatment decisions have to be drawn

individually taking into account patients preference, personal experience

and local equipment. We believe that ureteroscopy is preferable to ESWL

for treatment of distal ureteral calculi since it is significantly more

efficient with higher patient satisfaction.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Huffman JL, Bagley DH, Lyon ES: Treatment of distal ureteral calculi using rigid ureteroscope. Urology. 1982; 20: 574-7.

- Chaussy C, Schmiedt E, Jocham D, Brendel W, Forssmann B, Walther V: First clinical experience with extracorporeally induced destruction of kidney stones by shock waves. J Urol. 1982; 127: 417-20.

- Biyani CS, Cornford PA, Powell CS: Ureteroscopic holmium lasertripsy for ureteric stones. Initial experience. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1998; 32: 92-3.

- Watson GM, Wickham JE: Initial experience with a pulsed dye laser for ureteric calculi. Lancet. 1986; 1: 1357-8.

- Marberger M, Hofbauer J, Turk C, Hobarth K, Albrecht W: Management of ureteric stones. Eur Urol. 1994; 25: 265-72.

- el-Faqih SR, Husain I, Ekman PE, Sharma ND, Chakrabarty A, Talic R: Primary choice of intervention for distal ureteric stone: ureteroscopy or ESWL? Br J Urol. 1988; 62: 13-8.

- Pearle MS, Nadler R, Bercowsky E, Chen C, Dunn M, Figenshau RS, et al.: Prospective randomized trial comparing shock wave lithotripsy and ureteroscopy for management of distal ureteral calculi. J Urol. 2001; 166: 1255-60.

- Kapoor DA, Leech JE, Yap WT, Rose JF, Kabler R, Mowad JJ: Cost and efficacy of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy versus ureteroscopy in the treatment of lower ureteral calculi. J Urol. 1992; 148: 1095-6.

- Peschel R, Janetschek G, Bartsch G: Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy versus ureteroscopy for distal ureteral calculi: a prospective randomized study. J Urol. 1999; 162: 1909-12.

- Segura JW: Ureteroscopy for lower ureteral stones. Urology. 1993; 42: 356-7.

- Segura JW, Preminger GM, Assimos DG, Dretler SP, Kahn RI, Lingeman JE, et al.: Ureteral Stones Clinical Guidelines Panel summary report on the management of ureteral calculi. The American Urological Association. J Urol. 1997; 158: 1915-21.

- Ather MH, Memon A: Therapeutic efficacy of Dornier MPL 9000 for prevesical calculi as judged by efficiency quotient. J Endourol. 2000; 14: 551-3.

- Knoll T, Alken P, Michel MS: Progress in Management of Ureteric Stones. EAU Update Series. 2005; 3: 44-50.

- Miller OF, Kane CJ: Time to stone passage for observed ureteral calculi: a guide for patient education. J Urol. 1999; 162: 688-90.

- Tiselius HG, Ackermann D, Alken P, Buck C, Conort P, Gallucci M: Guidelines on urolithiasis. Eur Urol. 2001; 40: 362-71.

- Shah DO, Matlaga BR, Assimos DG: Selecting Treatment for Distal Ureteral Calculi: Shock Wave Lithotripsy versus Ureteroscopy. Rev Urol. 2003; 5: 40-4.

- Wills TE, Burns JR: Ureteroscopy: an outpatient procedure? J Urol. 1994; 151: 1185-7.

- Stoller ML, Wolf J: Endoscopic ureteral injuries. In: McAnich JW (ed.), Traumatic and Reconstructive Urology. Philadelphia, WB Sanders. 1996; pp. 199-205.

- Harmon WJ, Sershon PD, Blute ML, Patterson DE, Segura JW: Ureteroscopy: current practice and long-term complications. J Urol. 1997; 157: 28-32.

- Schuster TG, Hollenbeck BK, Faerber GJ, Wolf JS Jr: Complications of ureteroscopy: analysis of predictive factors. J Urol. 2001; 166: 538-40.

- Fong YK, Ho SH, Peh OH, Ng FC, Lim PH, Quek PL, et al.: Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy and intracorporeal lithotripsy for proximal ureteric calculi—a comparative assessment of efficacy and safety. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2004; 33: 80-3.

- Kelly JD, Keane PF, Johnston SR, Kernohan RM: Laser lithotripsy for ureteric calculi: results in 250 patients. Ulster Med J. 1995; 64: 126-30.

- Denstedt JD, Wollin TA, Sofer M, Nott L, Weir M, D’A Honey RJ: A prospective randomized controlled trial comparing nonstented versus stented ureteroscopic lithotripsy. J Urol. 2001; 165: 1419-22.

- Ilker Y, Turkeri LN, Korten V, Tarcan T, Akdas A: Antimicrobial prophylaxis in management of urinary tract stones by extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy: is it necessary? Urology. 1995; 46: 165-7.

- Claes H, Vandeursen R, Baert L: Amoxycillin/clavulanate prophylaxis for extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy—a comparative study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989; 24: 217-20.

- Hosking DH, Smith WE, McColm SE: A comparison of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy and ureteroscopy under intravenous sedation for the management of distal ureteric calculi. Can J Urol. 2003; 10: 1780-4.

- Miroglu C, Saporta L: Transurethral ureteroscopy: is local anesthesia with intravenous sedation sufficiently effective and safe? Eur Urol. 1997; 31: 36-9.

- Anagnostou T, Tolley D: Management of ureteric stones. Eur Urol. 2004; 45: 714-21.

- Sharma DM, Maharaj D, Naraynsingh V: Open mini-access ureterolithotomy: the treatment of choice for the refractory ureteric stone? BJU Int. 2003; 92: 614-6.

- Gettman MT, Segura JW: Management of ureteric stones: issues and controversies. BJU Int. 2005; 95: 85-93.

- Hochreiter WW, Danuser H, Perrig M, Studer UE: Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy for distal ureteral calculi: what a powerful machine can achieve. J Urol. 2003; 169: 878-80.

- Di Pietro C, Micali S, De Stefani S, Celia A, De Carne C, Bianchi G: Dornier Lithotripter S. The first 50 treatments in our department. Urol Int. 2004; 72: 48-51.

____________________

Accepted after revision:

July 24, 2006

_______________________

Correspondence address:

Dr. Ibrahim Fathi Ghalayini

Associate Professor of Urology

P.O. Box 940165, Amman, 11194, Jordan

Fax: + 00 962 6 568-7422

E-mail: ibrahimg@just.edu.jo

EDITORIAL COMMENT

Ghalayini

and colleagues have prospectively studied the efficacy and patients satisfaction

in a comparative non -randomized study comparing ureteroscopy and shock

wave lithotripsy for distal ureteric stone. An informed consent was taken

and patients opted for one or the other treatment arm.

The

authors have done this study quite amicably and should be congratulated

for the honest description of the results. However, there are several

factors that should be emphasized before incorporating their findings

into every day clinical practice.

Efficacy

of the treatment for distal ureteric stone is judged not only by stone

free rate but other factors like need for re-treatment, ancillary procedure

requirement and admission, all but the last are analyzed by efficient

quotient (1-3). In this work 80% patient falling ureteroscopy required

hospitalization, this is contrary to contemporary experience as admission

following ureteroscopy for distal ureteric stone is only required in a

small minority. Most often it is for social reason, lack of follow-up,

heath care facility (home care, trained general practitioner etc) and

less commonly for complications.

The

other major difference between ureteroscopy and shock wave lithotripsy

is the quantum of complications. The incidence of major complications

like ureteric avulsion and ureteric perforations are fortunately rare

but still a potential possibility. In the present work, the authors have

found a very low incidence of complications in the 2 groups with no major

complication. Need for anesthesia is another major difference between

the 2 procedures. Although in women with distal ureteric calculi requiring

treatment, ureteroscopy could be done under intravenous sedation, in men

the better tolerance of SWL must be weighed against the higher success

rate of ureteroscopy. If both treatment modalities are available, patients

with small distal ureteric calculi, in whom ureteroscopy is likely to

be successful, should be informed of and offered their choice of either

treatment modality. Overall, the study adds nicely to rapidly growing

body of evidence that ureteroscopy is a better option of treatment for

stones moderately large to larger stones (3).

REFERENCES

- Clayman R, McClennan B, Garvin T: Lithostar: An electromagnetic shock wave acoustic unit for extracorporeal lithotripsy. J. Endourol. 1989; 3:307.

- Ather MH, Akhtar S: Appropriate cutoff for treatment of distal ureteral stones by single session in situ extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Urology. 2005; 66: 1165-8.

- Ather MH, Memon A: Therapeutic efficacy of Dornier MPL 9000 for prevesical calculi as judged by efficiency quotient.J Endourol. 2000; 14: 551-3.

Dr. M.

Hammad Ather

Section of Urology, Department of Surgery

Aga Khan University

Karachi, Pakistan

E-mail: hammad.ather@aku.edu

EDITORIAL COMMENT

The

aim of surgical management of ureteral calculi is to obtain complete stone

free state with minimal morbidity to the patient. Ureteral calculi are

often associated with obstruction and treatment should be done to prevent

irreversible damage to the kidney. Mainly 3 factors are important for

the selection of treatment modality. First stone related factors i.e.

stone localization, size, composition, duration, degree of obstruction,

second clinical factors as patient tolerance to intervention, symptomatic

events, patient expectations, infections, solitary kidney, abnormal anatomy

and the third, technical factors i.e. available equipment and cost.

Considerable

progress has been made in the medical and surgical management of urolithiasis

over the past 25 years. Three minimally invasive techniques are currently

available, which significantly reduced the morbidity of stone removal:

percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PNL), rigid and flexible ureterorenoscopy

(URS) and shock wave lithotripsy (SWL). For many clinicians, ureteroscopy

with extraction or intracorporeal lithotripsy is the preferred treatment

of distal ureteral calculi. However, shock wave lithotripsy with or without

stent implantation is the treatment of choice in some centers. Studies

suggest that either SWL or URS are useful options for the management of

distal ureteral calculi. Ureteroscopic access is frequently useful for

the management of ureteral calculi when shock wave lithotripsy is failed

and for complex calculi because shock wave lithotripsy is not the ideal

modality for the management of this kind of calculi. Several investigators

do not advocate the use of shock wave lithotripsy for the treatment of

distal and prevesicular stones due to difficult positioning of the patients

for these procedures in which prone or modified sitting position is preferred

in these situations. The advances in the fiber optic lens systems resulted

in the manufacturing of smaller ureteroscopic instruments, which enabled

widespread use of routine diagnostic and therapeutic procedures within

the ureter and kidney. Open surgery is rarely preferred today but it remains

as an option for a salvage procedure. Alternatively laparoscopic surgery

is a minimally invasive option that can be used in circumstances where

open surgery may have been indicated.

As

this study showed URS and ESWL modalities share an overall high success

rate with low morbidity and both modalities has also proven to be effective

and safe therefore the selection of the optimal treatment for distal ureteral

calculi remains one of the most controversial issues currently in endourology.

Although

ureterecospic treatment is more invasive than ESWL the patient may achieve

a stone free status with a single procedure. ESWL is less invasive but

a drawback from the patients’ perspective may be the long follow-up

until a stone free state or the risk of a requirement for additional invasive

procedures and retreatment need associated with ESWL. Conversely patient

may favor ESWL because of fear of the anesthesia requirement associated

with ureteroscopy and the possibility of a temporary ureteral stent implementation.

ESWL can be done as an outpatient procedure with sedation.

ESWL

is equivalent to URS for smaller stones (less than 1 cm) but becomes significantly

less efficient with larger stones. Generally ESWL was recommended for

small and solitary stones, and URS for large or multiple stones. Not expectedly,

smaller stones (less than 5 mm) that had not passed spontaneously by 3

weeks can be more efficiently treated with URS, because they are the most

difficult to localize and focus with ESWL.

A

review of the literature revealed that the mean stone free rate for ESWL

are 50-95% and for ureteroscopy 96-100%, retreatment rates are 27-50%

for ESWL and 0.8-19% for ureteroscopy.

Recent

studies suggest a tendency from noninvasive ESWL to ureteroscopy. As depicted

in the current study patient satisfaction is also better in URS.

Choice

of treatment modality depends on the current data regarding effectivity,

complications and cost-effectiveness, physicians’ expertise and

available equipment. The patients preferences as anesthesia acceptance

or deny and immediate cure expectations are also the factors that effecting

the choice. The patient should be informed for the existing active treatment

modalities and their relative benefits and risks.

REFERENCES

- Ceylan K, Sunbul O, Sahin A, Gunes M: Ureteroscopic treatment of ureteral lithiasis with pneumatic lithotripsy: analysis of 287 procedures in a public hospital. Urol Res. 2005; 33: 422-5.

- Kupeli B, Biri H, Isen K, Onaran M, Alkibay T, Karaoglan U, Bozkirli I: Treatment of ureteral stones: comparison of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy and endourologic alternatives. Eur Urol. 1998; 34: 474-9.

- Peschel R, Janetschek G, Bartsch G: Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy versus ureteroscopy for distal ureteral calculi: a prospective randomized study. J Urol. 1999; 162: 1909-12.

- Shah DO, Matlaga BR, Assimos DG: Selecting treatment for distal ureteral calculi: shock wave lithotripsy versus ureteroscopy. Rev Urol. 2003; 5: 40-4.

Dr. Kadir

Ceylan

Department of Urology, School of Medicine

Yuzuncu Yil University

Van, Turkey

E-mail: drceylan26@yahoo.com

EDITORIAL COMMENT

The optimal treatment for distal ureteral stones remains an important question in urology. While there have been multiple studies addressing this issue, there have been only 2 prospective randomized trials to date, each with a contradictory answer. In a multi-institutional trial Pearle et al. (1) concluded that shock wave lithotripsy is preferable while Peschel et al. (2) instead determined that ureteroscopy should be first line treatment. Of note, these conclusions were not based on stone free rates alone, but instead included results from patient questionnaires addressing postoperative pain and satisfaction. Due to its non-randomized study design and inherent risk of selection bias, this work by Ghalayini and colleagues does not provide the definitive answer for the treatment of distal ureteral stones. However, it does provide an interesting insight into what patients find important regarding their procedure. Despite taking significantly less oral pain medication for a shorter period of time and having fewer complications, patients in the shock wave lithotripsy group had a lower level of satisfaction than patients undergoing ureteroscopy. It is important to note that the questionnaire used to obtain these results has not been validated, but it is clear that the global assessment of patient satisfaction was composed of more than just postoperative discomfort. The authors suggest that the decreased satisfaction in the shock wave lithotripsy group was due to the more prolonged time for stone passage relative to ureteroscopy. While no analysis was performed directly addressing this conclusion, shorter time to stone passage following ureteroscopy is a possible explanation as to why patients favored a procedure that was clearly more painful. Definitive proof supporting this conclusion will require further study, but when counseling patients on shock wave lithotripsy versus ureteroscopy for treatment of distal ureteral stones, the patient’s feelings regarding stone passage time may help suggest one procedure over the other.

REFERENCES

- Pearle MS, Nadler R, Bercowsky E, Chen C, Dunn M, Figenshau RS, et al.: Prospective randomized trial comparing shock wave lithotripsy and ureteroscopy for management of distal ureteral calculi. J Urol. 2001; 166: 1255-60.

- Peschel R, Janetschek G, Bartsch G: Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy versus ureteroscopy for distal ureteral calculi: a prospective randomized study. J Urol. 1999; 162: 1909-12.

Dr. Kyle Anderson

Dept of Urology, Section of Endourology

University of Minnesota

Edina, Minnesota, USA