TRANSURETHRAL

RESECTION OF THE PROSTATE FOR THE TREATMENT OF LOWER URINARY TRACT SYMPTOMS

RELATED TO BENIGN PROSTATIC HYPERPLASIA: HOW MUCH SHOULD BE RESECTED?

(

Download pdf )

doi: 10.1590/S1677-55382009000600007

ALBERTO A. ANTUNES, MIGUEL SROUGI, RAFAEL F. COELHO, KATIA R. LEITE, GERALDO DE C. FREIRE

Division of Urology, University of Sao Paulo Medical School, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Objective:

To assess the impact of the percent of resected tissue on the improvement

of urinary symptoms.

Materials and Methods: The study included

a prospective analysis of 88 men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Patients

were divided in three groups according to the percent of resected tissue:

Group 1 < 30%; Group 2, 30% to 50%; and Group 3, > 50%. Each patient

was re-evaluated 3 months after surgery. We assessed the international

prostatic symptom score, nocturia and serum prostate specific antigen

levels.

Results: All patients presented a significant

decrease on mean International Prostate System Score (IPSS) (23 to 5.9),

Quality of Life (QoL) (4.9 to 1.0) and nocturia (3.2 to 1.9). Variation

in the IPSS was 16.7, 16.6 and 18.4 for patients from Group 1, 2 and 3

respectively (P = 0.504). Although the three groups presented a significant

decrease in QoL, patients in Group 3 presented a significantly greater

decrease when compared to Group 1. Variation in QoL was 3.1, 3.9 and 4.2

for patients from Group 1, 2 and 3 respectively (p = 0.046). There was

no significant difference in nocturia variation according to the percent

of resected tissue (p = 0.504). Median pre and postoperative PSA value

was 3.7 and 1.9 ng/mL respectively. Patients from Group 1 did not show

a significant variation (p = 0.694). Blood transfusions were not required

in any group.

Conclusions: Resection of less than 30%

of prostatic tissue seems to be sufficient to alleviate lower urinary

tract symptoms related to benign prostate hyperplasia. However, these

patients may not show a significant decrease in serum PSA level.

Key

words: prostate; benign prostatic hyperplasia; transurethral

prostatectomy; symptom score; organ weight

Int Braz J Urol. 2009; 35: 683-91

INTRODUCTION

Benign

prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is the most common benign neoplasm in men.

By the age of 60, half of all men have histological evidence of BPH and

virtually all men have it by the age of 80 (1). Additionally, in a recent

retrospective study of more than one million men 50 years of age or older

in a managed care population from United States, BPH was among the four

prevalent diagnoses (2).

Despite the development of new minimally

invasive methods, transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) remains

the gold standard surgical treatment for lower urinary tract symptoms

(LUTS) related to BPH, with more than 90% of the patients reporting normal

or improved voiding, after 10-year follow-up period (3,4). The recommended

technique of TURP consists of complete removal of all adenomatous tissue

inside the surgical capsule (5). However, complication rates seem to be

related to resection time and the amount of resected tissue (6), and historical

data has shown that the amount of resected tissue during TURP has decreased

significantly over the last 10 years (7,8).

In fact, to date there is no consensus regarding

what amount of tissue should be resected during TURP. While some authors

have suggested that better clinical results after TURP may correlate with

the completeness of the resection of the obstructing adenoma (9,10), others

have shown that partial resection produces short-term functional results

comparable to those of standard TURP (11,12). The aim of this study was

to evaluate the impact of the percent of resected tissue (PRT) during

TURP on the short-term clinical outcome of patients with LUTS due to BPH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The

study comprised a prospective analysis of a cohort of 144 consecutive

men who underwent TURP for treatment of LUTS due to BPH between February

2006 and June 2007. After exclusion of 56 cases that were treated for

urinary retention, the final sample comprised of 88 patients. All these

patients had moderate or severe LUTS that were refractory to medical treatment

and were at least dissatisfied with their urinary condition. Patients

with neurogenic bladder or prostatic carcinoma were not considered for

analysis.

All patients underwent detailed physical

examination including digital rectal examination, blood chemistry, urine

analysis and serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) test. For assessment

of LUTS and QoL, we used the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS)

(13) and its appended 8th question related to quality of life (QoL). PSA

behavior was also analyzed. Prostate volume was measured through abdominal

ultrasound and estimated as length x width x height x 0.52. All patients

were operated on under spinal anesthesia with a 24-French Storz continuous-flow

resectoscope and a standard loop. The resected tissue was systematically

weighed immediately after the surgical procedure. Perioperative complications

were recorded if present. The urethral Foley catheter was removed from

all patients 48 hours after TURP and they were discharged home on the

third postoperative day. They were re-evaluated at 3 months for LUTS,

QoL, nocturia and serum PSA levels.

The PRT was calculated as the resected tissue

weight divided by the preoperative ultrasound prostate volume measurement

x 100. Patients were divided in three groups according to the PRT: Group

1 < 30%; Group 2 = 30% to 50%; and Group 3 > 50%. Table-1 shows

the baseline demographic characteristics of the three study groups. Mean

patient age, IPSS, nocturia, duration of symptoms, prostate weight and

serum PSA levels were similar between the groups. Regarding QoL, patients

from Group 3 presented a marginally significant higher mean score when

compared to patients from Group 1.

Since for the patient the most important

outcome parameter is satisfaction with symptomatic improvement, primary

end point was a change in QoL score according to the PRT. Secondary end

points were a change in IPSS, nocturia or serum PSA levels. For statistical

analysis we used the ANOVA test. Statistical analysis was performed using

the SPSS 12.0 for Windows software and significance was set as p = 0.05.

RESULTS

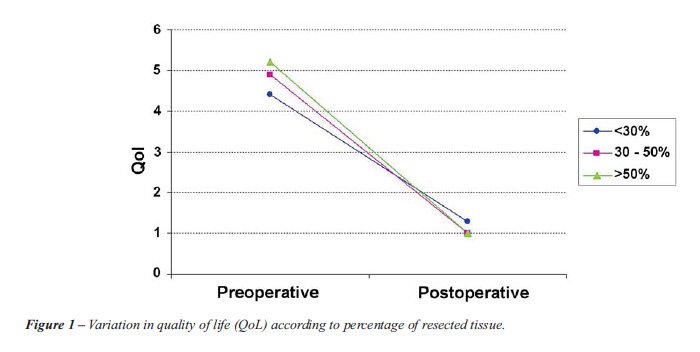

Mean resected tissue weight was 12.4 ± 4.4, 22.3 ± 7.4 and 33.8 ± 6.1 grams for patients from group 1, 2 and 3 respectively (p < 0.001). Mean pre and postoperative QoL score was 4.9 ± 1.0 and 1.0 ± 1.0 respectively. The three groups showed a significant improvement in QoL (mean 3.7 ± 0.3; p < 0.001), however, patients from Group 3 when compared to patients from Group 1 presented a significantly greater decrease (p = 0.046). Variation in QoL was 3.1 ± 0.3, 3.9 ± 0.2 and 4.2 ± 0.3 for patients from group 1, 2 and 3 respectively (Figure-1).

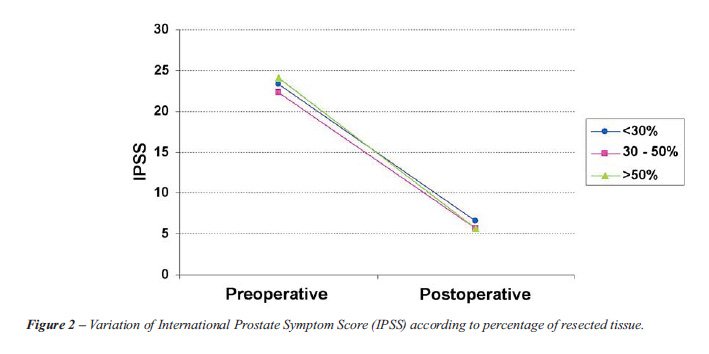

Mean pre and postoperative IPSS was 23.0

± 5.6 and 5.9 ± 4.6 respectively. There was a significant

decrease in IPSS among the three study groups (mean 17.1 ± 0.7;

p < 0.001), but despite a slight greater variation among patients from

group 3, no significant statistical difference in the IPSS variation according

to the PRT was observed (p = 0.561). Variation in IPSS was 16.7, 16.6

and 18.4 for patients from group 1, 2 and 3 respectively (Figure-2).

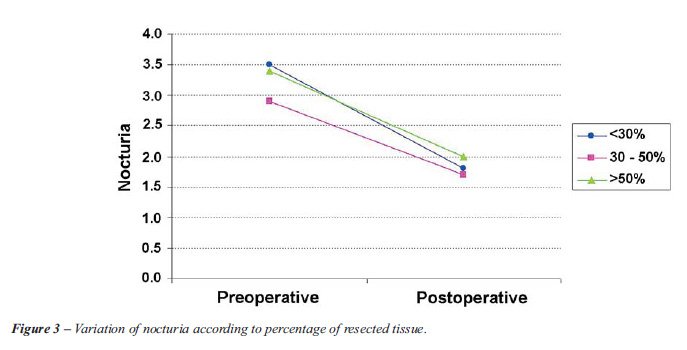

Mean pre and postoperative nocturia was

3.2 ± 1.5 and 1.9 ± 1.3 respectively. Again, the 3 groups

presented a significant decrease in nocturia (mean 1.4 ± 0.2; p

< 0.001). There was no significant difference in nocturia variation

according to the PRT (p = 0.504). Postoperative nocturia was 1.8 ±

1.3, 1.7 ± 1.4 and 2.0 ± 1.4 for patients from Group 1,

2 and 3 respectively (Figure-3).

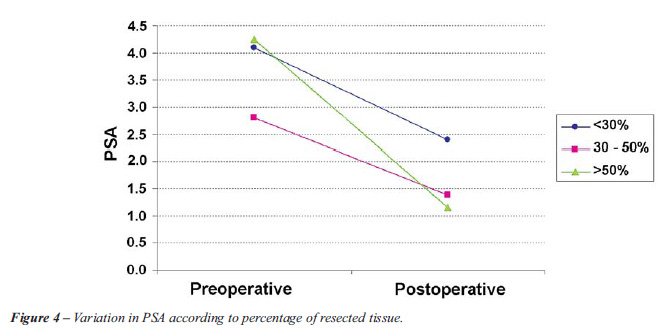

Median pre and postoperative PSA value was 3.7 ng/mL (0.3 - 24.8) and

1.9 ng/mL (0.2 - 11.0) respectively. While patients from group 2 and 3

presented a significant drop in PSA levels (p = 0.003 and p = 0.002 respectively),

patients from Group 1 did not show a significant variation in PSA levels

(p = 0.694). Median postoperative PSA levels were 2.4 (0.2 - 11.0), 1.4

(0.4 - 5.9) and 1.15 (0.3 - 5.4) for patients from Group 1, 2 and 3 respectively

(Figure-4). Blood transfusions were not required in any group.

COMMENTS

The

present study demonstrated that the amount of resected tissue seems to

have little impact on the short-term clinical outcome after TURP. Although

patients who had more than 50% of the prostatic tissue resected presented

a significantly greater decrease in QoL score when compared to patients

in Group 1, both groups presented a significant decrease when analyzed

individually. Variations in IPSS were also slightly greater among patients

from Group 3, but this figure was not statistically significant. Nocturia

was not influenced by the PRT.

Despite the proven efficacy of TURP, the

question of how much prostatic tissue should be resected has existed for

more than 70 years. While McCarthy stated in 1931 that resection of median

and lateral lobes should be performed until a free view into the bladder

was obtained, Blandy stated in 1978 that total resection of the adenoma

inside the surgical capsule between the bladder neck and the verumontanum

was necessary (12).

The recommended TURP technique consists

of complete removal of the entire adenoma inside the surgical capsule

(5). However, when performed in medically compromised elderly patients

with large prostates, this procedure may be associated with troublesome

bleeding and irrigating fluid absorption leading to TURP syndrome. Data

from 3861 consecutive patients with BPH who underwent TURP from 1971 to

1996 demonstrated that mortality, morbidity, and blood transfusions were

observed in 0.1%, 13.4% and 13.1% patients, respectively. The most significant

risk factors for blood transfusion were related to resection time, the

amount of tissue resected, age, and the decade in which the surgery was

performed (6). Regarding TURP syndrome, Mebust et al. (14), showed that

its incidence was greater in resections lasting longer than 90 minutes

and in those producing more than 45 grams of tissue. In the present series,

25% of the patients had more than 50% of the prostates resected, and no

case required blood transfusions or developed TURP syndrome.

To date, there is still no consensus regarding

the amount of prostatic tissue that should be resected during TURP. Despite

the initial recommendations by Nesbit (5), historical data has shown that

the amount of resected tissue has decreased significantly over time (7,8).

In the study of Borth et al. (7), mean weight of tissue resected in 1988

was 16.5g and decreased to 12.5g in 1998. In the series of Vela-Navarrete

et al. (8), mean volume resected in 1992 was 35.7 mL and decreased to

24.3 mL in 2002. In the series of Green et al. (15), which analyzed 432

patients who underwent TURP, the mean weight of tissue resected was 25.6

g and no surgeon resected more than 50% of the gland volume. In the present

series the mean resected tissue weight was 22.3 ± 10.2 grams, which

corresponded to a mean 42% of PRT.

Data analyzing the outcome of patients who

underwent complete or partial TURP have led to controversial results.

In the study of Chen et al. (9), these authors found a good relationship

between residual prostate weight ratio (weight after TURP divided by the

preoperative prostate weight) and clinical outcome variables among 40

patients who underwent TURP and were followed-up for 16 weeks. Their results

suggest that the better clinical results after TURP correlate significantly

with the completeness of the resection of the obstructing adenoma.

Conversely, Aagaard et al. (11) prospectively

assessed the long-term results of total TURP and minimal TURP in 167 patients

with obstructive symptoms caused by BPH and found that a significant relief

in obstructive and irritative symptoms was observed in both groups. Maximum

flow rate and post-void residual urine improvement were also similar between

the groups. Similarly, more recently, Agrawal et al. (12), in a prospective

and randomized study compared the hemiresection (complete resection of

one lateral lobe and the median lobe, if present) of the prostate to the

standard TURP. They found that the 2 groups had comparable improvement

in symptom scores and flow rates. Two patients required blood transfusions

and two developed TURP syndrome in the standard resection group and no

complications were observed in the hemiresection group.

PSA behavior after TURP is crucial during

patient follow-up and a subsequent rise in PSA may indicate prostate biopsy.

Studies have shown that PSA decreases drastically in patients who undergo

TURP. Fonseca et al. (16), showed that mean PSA levels declined 71% after

TURP, and 60 days after surgery the reduction reached its peak, stabilizing

afterwards. Mean PSA varied from 6.1 ng/mL before surgery to 1.7 ng/mL

after 60 days postoperatively. In the present series we demonstrated that

the amount of resected tissue might significantly influence PSA reduction.

Variation in PSA among patients who had less than 30% of prostate resected

was not significant and median postoperative PSA in this group was 2.4

ng/mL (0.2 - 11.0). Urologists must take into account the PRT when analyzing

the serum PSA in patients who have undergone TURP.

Some methodological limitations of the present

study must be considered. We did not analyze LUTS function through objective

measurements such as flow rates or residual urine. According to the American

Urological Association guidelines these are optional assessments for patients

with BPH who are candidates for surgical treatment (17). Follow-up was

limited, however, the scope of the study was to assess symptom relief

and previous data have suggested that no further symptom improvement would

be observed after 3 months of TURP (10). Finally, prostate volume was

measured by suprapubic rather than transrectal ultrasound. However, while

the transuretral route is considered to be more accurate in prostate size

determination, similar limitations exist for both methods (18).

CONCLUSIONS

Resection of less than 30% of prostatic tissue seems to be sufficient to alleviate LUTS related to BPH. However, these patients may not show a significant decrease in the serum PSA level. Analysis of PSA in men who have undergone TURP must take into account the PRT. Patients with more than 50% of resected tissue may present a greater variation in QoL scores.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Berry SJ, Coffey DS, Walsh PC, Ewing LL: The development of human benign prostatic hyperplasia with age. J Urol. 1984; 132: 474-9.

- Issa MM, Fenter TC, Black L, Grogg AL, Kruep EJ: An assessment of the diagnosed prevalence of diseases in men 50 years of age or older. Am J Manag Care. 2006; 12(4 Suppl): S83-9.

- Rassweiler J, Teber D, Kuntz R, Hofmann R: Complications of transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP)--incidence, management, and prevention. Eur Urol. 2006; 50: 969-79; discussion 980.

- Thomas AW, Cannon A, Bartlett E, Ellis-Jones J, Abrams P: The natural history of lower urinary tract dysfunction in men: minimum 10-year urodynamic followup of transurethral resection of prostate for bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol. 2005; 174: 1887-91.

- Nesbit RM: Transurethral prostatic resection. In: Campbell L, Harrison J (ed.), Urology. Philadelphia, Sounders. 1970; pp. 2479.

- Uchida T, Ohori M, Soh S, Sato T, Iwamura M, Ao T, et al.: Factors influencing morbidity in patients undergoing transurethral resection of the prostate. Urology. 1999; 53: 98-105.

- Borth CS, Beiko DT, Nickel JC: Impact of medical therapy on transurethral resection of the prostate: a decade of change. Urology. 2001; 57: 1082-5; discussion 1085-6.

- Vela-Navarrete R, Gonzalez-Enguita C, Garcia-Cardoso JV, Manzarbeitia F, Sarasa-Corral JL, Granizo JJ: The impact of medical therapy on surgery for benign prostatic hyperplasia: a study comparing changes in a decade (1992-2002). BJU Int. 2005; 96: 1045-8.

- Chen SS, Hong JG, Hsiao YJ, Chang LS: The correlation between clinical outcome and residual prostatic weight ratio after transurethral resection of the prostate for benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int. 2000; 85: 79-82.

- Hakenberg OW, Helke C, Manseck A, Wirth MP: Is there a relationship between the amount of tissue removed at transurethral resection of the prostate and clinical improvement in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol. 2001; 39: 412-7.

- Aagaard J, Jonler M, Fuglsig S, Christensen LL, Jorgensen HS, Norgaard JP: Total transurethral resection versus minimal transurethral resection of the prostate--a 10-year follow-up study of urinary symptoms, uroflowmetry and residual volume. Br J Urol. 1994; 74: 333-6.

- Agrawal MS, Aron M, Goel R: Hemiresection of the prostate: short-term randomized comparison with standard transurethral resection. J Endourol. 2005; 19: 868-72.

- Barry MJ, Fowler FJ Jr, O’Leary MP, Bruskewitz RC, Holtgrewe HL, Mebust WK, et al.: The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992; 148: 1549-57; discussion 1564.

- Mebust WK, Holtgrewe HL, Cockett AT, Peters PC: Transurethral prostatectomy: immediate and postoperative complications. a cooperative study of 13 participating institutions evaluating 3,885 patients. 1989. J Urol. 2002; 167: 999-1003; discussion 1004.

- Green JS, Bose P, Thomas DP, Thomas K, Clements R, Peeling WB, et al.: How complete is a transurethral resection of the prostate? Br J Urol. 1996; 77: 398-400.

- Fonseca RC, Gomes CM, Meireles EB, Freire GC, Srougi M: Prostate specific antigen levels following transurethral resection of the prostate. Int Braz J Urol. 2008; 34: 41-8.

- AUA Practice Guidelines Committee: AUA guideline on management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (2003). Chapter 1: Diagnosis and treatment recommendations. J Urol. 2003; 170: 530-47.

- Matthews GJ, Motta J, Fracehia JA: The accuracy of transrectal ultrasound prostate volume estimation: clinical correlations. J Clin Ultrasound. 1996; 24: 501-5.

____________________

Accepted after revision:

June 3, 2009

_______________________

Correspondence address:

Dr. Alberto Azoubel Antunes

Rua Barata Ribeiro, 490 / 76

Sao Paulo, 01308-000, Brazil

Fax: +55 11 3255-6372

Email: antunesuro@uol.com.br

EDITORIAL COMMENT

Antunes

and coauthors investigated the impact of the percent of resected tissue

(PRT) on the improvement of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). They

found that resection of less than 30% of prostatic tissue was sufficient

to alleviated LUTS although a significant variation on PSA levels was

not observed in this group. From the perspective of subjective outcome,

the authors’ observations indicate that symptom improvement can

be achieved regardless of the PRT.

I do not believe that LUTS is always due to enlarged prostate. I do believe

that LUTS does not need to always be related to prostate enlargement.

For example, Asian men have a similar frequency of prostatic obstruction

and more severe symptoms despite having a smaller prostate volume (1,2).

Thus, there is some reason in authors’ results. However, since the

authors could not provide objective data such as maximum flow rate, post-void

residual, frequency-volume charts, it is unknown whether these objective

parameters may also be improved regardless of the PRT. In addition, we

cannot know the lower limit of PRT for alleviating LUTS based on authors’

results. Furthermore, although TURP is a truly ablative procedure for

obstruction, authors did not perform pressure-flow studies. Thus, we do

not know how many patients who have detrusor underactivity or bladder

outlet obstruction were included in this study.

In summary, the value of the findings of Antunes and co-authors remain

unknown. Therefore, further studies are needed to answer the question

about the PRT for the improvement of LUTS/BPH and its possible mechanism.

REFERENCES

- Choi J, Ikeguchi EF, Lee SW, Choi HY, Te AE, Kaplan SA: Is the higher prevalence of benign prostatic hyperplasia related to lower urinary tract symptoms in Korean men due to a high transition zone index? Eur Urol. 2002; 42: 7-11.

- Tsukamoto T, Kumamoto Y, Masumori N, Miyake H, Rhodes T, Girman CJ, et al.: Prevalence of prostatism in Japanese men in a community-based study with comparison to a similar American study. J Urol. 1995; 154: 391-5.

Dr.

Jae-Seung Paick

Department of Urology

Seoul National University Hospital

Seoul, Korea

E-mail: jspaick@snu.ac.kr

EDITORIAL COMMENT

In this

paper Antunes et al. address the correlation between the amount of resected

tissue during transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) for benign

prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and the outcome of the procedure. Their conclusions

are that “resection of less than 30% of prostatic tissue seems to

be sufficient to alleviate lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) related

to BPH”.

On one hand, our classical idea of TURP is as much as complete removal

of adenomatous tissue, mimicking an open simple prostatectomy, especially

when operating on healthy patients without high surgical risk. On the

other hand, the concept by Antunes et al. might sound really appealing

because it obviously means reduced operative time and operative risks,

as we all know that complications of TURP are related to the duration

of the procedure, and it also means expanding indications of TURP to larger

prostates.

However, we think that their final message can be misleading and the results

have to be critically analyzed as the study suffers from some major methodological

flaws.

Regarding the study rationale: how can you offer patients a procedure

that is planned as “incomplete” from the beginning; how do

you inform the patients, in this series who are not too old and probably

have a low ASA score, about the procedure ?

The authors divided their patients in 3 cohorts according to the amount

of resected tissue. Unfortunately, from a methodological point of view,

this was the result of a retrospective analysis, while they ought to stratify

and then randomize the patients preoperatively. Moreover, the operator

should know exactly when to stop before beginning the procedure not while

operating. As no selection criteria are reported one can imagine that

the operator decided arbitrarily to stop the resection based on personal

experience. However, TURP is the gold standard in surgical treatment of

BPH because the technique has been standardized following specific anatomic

landmarks so that results among different centers can be compared.

Which patient would benefit from a less than 30% TURP? Will we ever be

able to understand when 30% (of adenomatous tissue or of the whole gland?)

has been resected? How will we teach trainees to stop resection in order

to gain good functional results? In our personal experience we had, of

course, cases where we had to stop resecting because extensive blood loss

or general perioperative complications occurred. And most of them functionally

did fairly well afterwards.

As recognized by the authors themselves, objective outcome parameters,

i.e. maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax) and post voiding residual urine

volume (PRV), are missing here. Actually, it is suggested by some authors

that a pressure/flow study had to be done when acting within the framework

of a clinical trial. Moreover, the follow-up (3 months) is really too

short here (also considering from current literature long-term data are

already available for TURP). And the problem is not that, as the authors

commented, “no further improvement might be observed…”.

In contrast, a worsening of the symptoms can be observed. That is why

long-term data are needed when evaluating any new minimally invasive surgical

procedure for BPH treatment.

In conclusion, we completely agree that “for the patient the most

important parameter is satisfaction with the symptomatic improvement”.

This is the reason why we will continue to perform and to teach a complete

TURP until a reproducible “mini-TURP” technique is established.

Dr.

Riccardo Autorino &

Dr. Marco De Sio

Clinica Urologica

Seconda Università degli Studi

Napoli, Italy

E-mail: ricautor@tin.it