PATIENT

POSITION AND SEMI-RIGID URETEROSCOPY OUTCOMES

( Download

pdf )

FERNANDO KORKES, ANTONIO C. LOPES-NETO, MARIO H. E. MATTOS, ANTONIO C. L. POMPEO, ERIC R. WROCLAWSKI

Division of Urology, ABC Medical School, Santo Andre, Sao Paulo, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

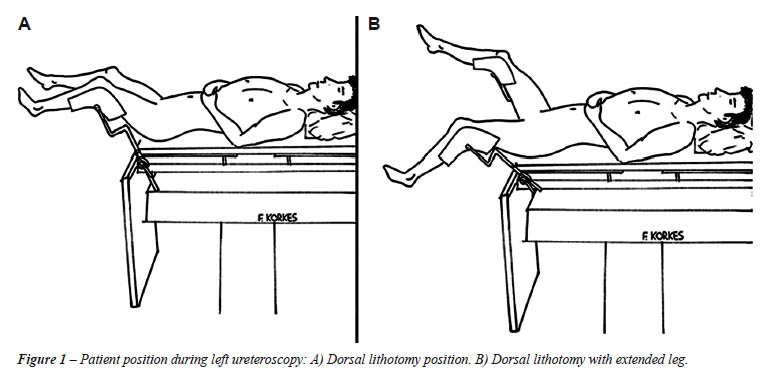

Two positions have been reported for ureteroscopy (URS): dorsal lithotomy

(DL) position and dorsal lithotomy position with same side leg slightly

extended (DLEL). The aim of the present study was to compare the outcomes

associated with URS performed with patients in DL vs. DLEL position.

Materials and Methods: A total of 98 patients

treated for ureteral calculi were randomized to either DL or DLEL position

during URS, and were prospectively followed. Patients, stone characteristics

and operative outcomes were evaluated.

Results: Of the 98 patients included in

the study, 56.1% were men and 43.9% women with a mean age of 42.6 ±

16.8 years. Forty-eight patients underwent URS in DL position and 50 in

DLEL position. Patients’ age, mean stone size and location were

similar between both groups. Operative time was longer for the DL vs.

DLEL group (81.0 vs. 62.0 minutes, p = 0.045), mainly for men (95.2 vs.

63.9 minutes, p = 0.023). Mean fluoroscopy use, complications and success

rates were similar between both groups.

Conclusions: Most factors associated with

operative outcomes during URS are inherent to patient’s condition

or devices available at each center, and therefore cannot be changed.

However, leg position is a simple factor that can easily be changed, and

directly affects operative time during URS. Even though success and complication

rates are not related to position, placing the patient in dorsal lithotomy

position with an extended leg seems to make the surgery easier and faster.

Key

words: ureteroscopy; ureteral calculi; lithotripsy; prospective

studies; lithiasis; urinary catheterization

Int Braz J Urol. 2009; 35: 542-50

INTRODUCTION

Ureteroscopy

(URS) has gained widespread use for the treatment of ureteral stones (1,2).

For most endoscopic procedures, patients are placed in the standard dorsal

lithotomy position and the perineum flush with the end of the cystoscopy

table. Two positions have been reported for URS procedures: dorsal lithotomy

position with legs supported in stirrups with minimal flex at the hips

(DL) (3,4); and dorsal lithotomy position with one leg (same side of ureteral

stone) slightly extended, and the hip abducted (DLEL) (5) (Figure-1).

This position has the theoretical advantage of minimizing the angulation

of the ureter, facilitating passage and advancement of the ureteroscope

(6,7).

However, different groups have adopted

both positions, and after video cameras had been selected for such procedures,

many surgeons have subsequently used the DL position. To our knowledge,

no studies have assessed the differences between these two approaches.

The aim of the present study was to compare the outcomes associated with

URS performed with patients in DL vs. DLEL position, significant operative

time, stone free and complication rates. As secondary outcomes, fluoroscopy

time, need for ureteral dilatation, use of ureteral stents and length

of hospital stay was also assessed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A

total of 98 patients treated for ureteral calculi at a single institution

from January 2004 to January 2008 were randomized to either DL or DLEL

position during URS, and were prospectively followed. All patients were

operated by second-year-residents-in-training, under supervision of the

same urologist (ACLN), always as first assistant (total of eight residents).

The ureteroscope (7.5F rigid ureteroscope, Karl Storz, Germany), fluoroscopy,

video monitor, baskets and irrigation devices were the same for both groups.

Balloon ureteral dilatation was performed in selected cases for technical

difficulties, and ureteral assess was always obtained after passing two

guide wires. Lithotripsy was performed with pneumatic lithotripter (Swiss

Lithoclast, Electro Medical Systems, Switzerland) under general or regional

anesthesia. A 6F or 7F ureteral stent was inserted at the end of the procedure

according to surgeon’s judgment.

Patients and stone characteristics and operative

outcomes were evaluated. Patients included in the study had ureteral calculi

to be treated surgically. Exclusion criteria included the presence of

infection, inadequate follow-up or hip limitations. Two patients were

excluded from the study. Main outcomes to be assessed included operative

time, fluoroscopy time, intra-operative complications, postoperative complications,

stone free rate, use of ureteral stents and length of hospital stay. Primary

end-point was to leave the patient stone free with minimal morbidity,

in a short period of time and with low radiation exposition. Statistical

analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences

software (SPSS 13.0 for Mac OS X, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL. USA). Student’s-t

test-was used to compare means and chi-square to compare categorical outcome

variables. Statistical significance was determined at p value less than

0.05. All patients or parents/tutors signed an informed consent form,

and the institutional review board approved the present study.

RESULTS

Of

the 98 patients included in the study, 55 (56.1%) were men and 43 (43.9%)

women with a mean age of 42.6 ± 16.8 years (range 9 - 84 years).

Forty-eight patients underwent URS in DL position and 50 in DLEL position.

Patients’ age, mean stone size and location were similar between

both groups (Table-1).

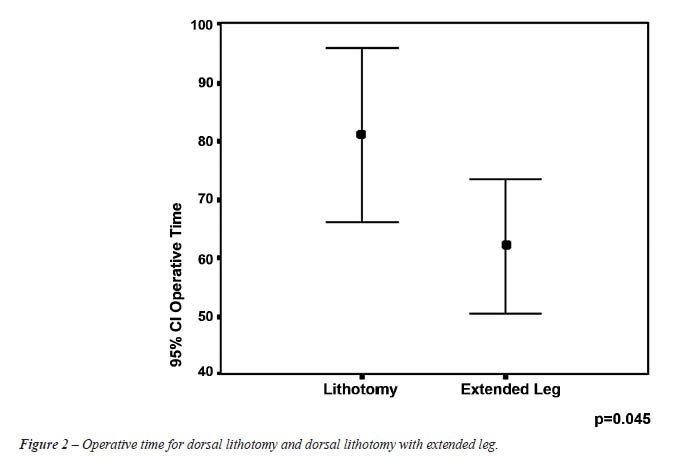

Operative outcomes for both groups are shown in Table-2. Operative time

was longer for the DL vs. DLEL group (81.0 vs. 62.0 minutes, p = 0.045,

Figure-2). Mean fluoroscopy use, complications and success rates were

similar between both groups (Table-2). If men vs. women were compared

in both groups, operative time was 95.2 vs. 64.5 minutes (p = 0.036) for

DL and 63.9 vs. 59.5 minutes (p = 0.709) for DLEL. If DL men vs. DLEL

men were compared, there was also a significant difference (p = 0.023),

which did not occur between DL women vs. DLEL women (p = 0.668).

The intra-operative complication rate was 3.1%, similar between both groups (p = 0.371), with medical vs. surgical complications accounting for 1.0 vs. 2.1%. Complications included one case of bronchospasm requiring tracheal intubation and 2 cases that required open conversion (one for ureteral damage while treating a large proximal stone in the DL group and one in DLEL group due to failure to access a large proximal stone). Minor complications occurred in 13.3% of the patients and included minor mucosal damage (9.2%), equipment malfunction (3.1%) and failure to place the ureteral stent (1.0%).

COMMENTS

Intracorporeal

lithotripsy technology has made it possible to successfully access and

treat virtually any stone within the upper urinary tract (1,8). Operative

outcomes have been associated with several factors, such as stone size,

stone location, energy source for lithotripsy, balloon dilatation, duration

of stone disease, surgeon’s experience, etc. (1,9-13). Most of these

factors are inherent to patient’s condition or devices available

at each center, and therefore cannot be changed. However, leg position

is a simple factor that directly affects ureteral access and kinking and

can easily be changed (7).

Different leg positions have been used

during URS procedures. The position of the patient with the same side

leg lower and medially positioned and with the other leg higher and more

laterally positioned has the theoretical advantage of straightening the

ureteral angle. Angus et al. have demonstrated in a radiographic study

that the ureteral angle at the iliac vessels level straightens according

to patient position, even though it does not interfere with the intramural

portion of the ureter (7). However, other factors might also interfere

such as the angle between the urethra/bladder neck and the ureteral orifice.

It is noteworthy that the role of patient’s position in URS outcomes

has never, to our knowledge, been previously evaluated, and clinical studies

are necessary to validate this experimental study. In fact, several studies

that evaluate URS outcomes do not in fact mention which position patients

were placed during procedures (1,10,14).

Our study has some important findings.

First, we have observed longer operative time when patients were in DL

vs. DLEL position. Different authors have used different leg positions

during URS (3-6), and according to our study, this detail directly affects

the operative time. This observation might reflect an increased difficulty

both to access the ureter and also that kinking in the ureter produces

to stone fragmentation and removal, subsequently taking a longer time

to access the ureter. Therefore, the theoretical support for the DLEL

position might be correct. Since this observation, our group has adopted

the DLEL as the standard position for URS. DLEL might not only straighten

the ureter to be assessed, but also with the flexed leg, the surgeon and

the assistant have a better working space.

Second, this difference was even more important

when operating men, resulting in a significant decrease in operative time

with DLEL position (p = 0.02). For men, the extended leg might bring an

additional benefit of straightening and aligning the urethra, which did

not occur in women (p = 0.668).

Third, complication and success rates were

similar for DL vs. DLEL groups, and both positions are feasible. Although

surgery might be easier and faster when patients are positioned in DLEL,

if for any reason the patient is positioned in DL, surgical outcomes are

expected to be the same. If there are limitations regarding cystoscopy

table positioning, URS can still be performed safely.

Our study has some limitations. First,

this was not a blinded study, as the surgeon was aware of leg position.

Nevertheless, we believe that this bias does not seem to affect surgical

procedures. Further studies evaluating the length of time spent in each

stage of surgery (bladder access, ureteral access, lithotripsy, ureteral

stenting) as well as subjective impression of the level of difficulty

according to patient position could produce additional information. Moreover,

other important factors such as stone composition were not evaluated in

the present study. However, this limitation is the same as in a clinical

setting when this information cannot be obtained preoperatively. Moreover,

as previously stated, stone composition is another factor that cannot

be modified preoperatively, differently from leg position.

Complication and ureteral stenting rates

were also slightly higher than in larger series. Possible reasons for

these findings include the facts that these patients were operated by

residents-in-training and as this population of patients have a great

difficulty in fixing an appointment with the urologist, as we primarily

treat large (mean size 9.9 mm) and chronic (mean history time of 148 days)

ureteral calculi. In this subset of patients, more complications are expected

(15), and ureteral stenting can be beneficial (16). One case required

open conversion due to ureteral avulsion while treating a large proximal

stone, a rare complication of this procedure (this was the only event

in our series of more than 900 ureteroscopies performed); the other patient

had a 12 mm proximal stone that could not be reached with the ureteroscope.

As we do not have a flexible ureteroscope or a flexible nephroscope, our

option was to convert to an open surgery and remove the stone, with an

unremarkable postoperative evolution.

In conclusion, patient position during

URS directly affects operative time. Even though success and complication

rates are not related to position, placing the patient in dorsal lithotomy

position with an extended leg seems to make the surgery easier and faster,

specially when operating males.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Preminger GM, Tiselius HG, Assimos DG, Alken P, Buck C, Gallucci M, et al.: 2007 guideline for the management of ureteral calculi. J Urol. 2007; 178: 2418-34.

- Rofeim O, Yohannes P, Badlani GH: Does laparoscopic ureterolithotomy replace shock-wave lithotripsy or ureteroscopy for ureteral stones? Curr Opin Urol. 2001; 11: 287-91.

- Ziaee SA, Halimiasl P, Aminsharifi A, Shafi H, Beigi FM, Basiri A: Management of 10-15-mm proximal ureteral stones: ureteroscopy or extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy? Urology. 2008; 71: 28-31.

- Watterson JD, Girvan AR, Beiko DT, Nott L, Wollin TA, Razvi H, et al.: Ureteroscopy and holmium:YAG laser lithotripsy: an emerging definitive management strategy for symptomatic ureteral calculi in pregnancy. Urology. 2002; 60: 383-7.

- Lopes Neto AC, Gava MM, Mattos MHE, Borreli M, Wroclawski ER: Treatment of ureteral calculi by ureteroscopy: experience of 100 cases at the Faculdade de Medicina do ABC (FMABC – Medical School). Einstein. 2004; 2: 28-32.

- Su LM, Sosa ES: Ureteroscopy and Retrograde Ureteral Access. In: Walsh PC (ed.), Campbell’s Urology. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2002; pp. 3314.

- Angus DG, Webb DR: Influence of hip flexion on the course of the ureter. Ureteroscopic implications. Eur Urol. 1988; 14: 287-90.

- Preminger GM, Tiselius HG, Assimos DG, Alken P, Buck AC, Gallucci M, et al.: 2007 Guideline for the management of ureteral calculi. Eur Urol. 2007; 52: 1610-31.

- Al-Awadi K, Kehinde EO, Al-Hunayan A, Al-Khayat A: Iatrogenic ureteric injuries: incidence, aetiological factors and the effect of early management on subsequent outcome. Int Urol Nephrol. 2005; 37: 235-41.

- Leijte JA, Oddens JR, Lock TM: Holmium laser lithotripsy for ureteral calculi: predictive factors for complications and success. J Endourol. 2008; 22: 257-60.

- Korkes F, Gomes SA, Heilberg IP: Diagnosis and treatment of ureteral calculi. J Bras Nefrol. 2009; 31: 55-61.

- Natalin R, Xavier K, Okeke Z and Gupta M: Impact of obesity on ureteroscopic laser lithotripsy of urinary tract calculi. Int Braz J Urol. 35: 36-41; discussion 41-2, 2009.

- Fuganti PE, Pires SR, Branco RO and Porto JL: Ballistic ureteroscopic lithotripsy in prepubertal patients: a feasible option for ureteral stones. Int Braz J Urol. 32: 322-7; discussion 327-9, 2006.

- Mugiya S, Ozono S, Nagata M, Takayama T, Nagae H: Retrograde endoscopic management of ureteral stones more than 2 cm in size. Urology. 2006; 67: 1164-8; discussion 1168.

- Brito AH, Mitre AI, Srougi M: Ureteroscopic pneumatic lithotripsy of impacted ureteral calculi. Int Braz J Urol. 2006; 32: 295-9.

- Hao P, Li W, Song C, Yan J, Song B, Li L: Clinical evaluation of double-pigtail stent in patients with upper urinary tract diseases: report of 2685 cases. J Endourol. 2008; 22: 65-70.

____________________

Accepted after revision:

June 8, 2009

_______________________

Correspondence address:

Dr. Fernando Korkes

Rua Pirapora, 167

São Paulo, SP, 04008-060, Brazil

Fax: + 55 11 3884-2233

E-mail: fkorkes@terra.com.br

EDITORIAL COMMENT

Ureteroscopy

is the first line treatment for ureteral lithiasis except in some cases.

Perez-Castro et al. described the technique of lowering the contralateral

limbs to facilitate the expansion and advancement of the ureteroscope

(1). Currently, most of the groups perform the procedure by telesurgery

in the classic lithotomy position, although the position has been modified

to improve access and to facilitate the extraction and removal of stone

fragments. In this article, the authors analyzed the results of ureteroscopy

in two positions; classic lithotomy and lithotomy with homolateral leg

extended, referenced by other authors (2), and they have observed significant

differences in surgical time in men (not in women), without significant

differences in the other parameters analyzed. Endourology techniques have

been performed in different positions to improve the access to the ureter.

Angus et al. reported that increasing the degree of the lithotomy position

improves the access to the iliac ureter (3). On the other hand, Bercowsky

et al. studied infundibulo-pelvic angle of lower calyx and they found

that the lower pole infundibulo-pelvic angle broadens when the patient

lies in a prone 20-degree head down position (4). Herrell et al. used

flank position in ureteroscopy to treat complex calyceal lithiasis because

the extraction is facilitated due to gravity (5).

The results published in this article by

Korkes et al. show that lithotomy with homolateral extended leg position

is a valid approach for ureteral lithiasis and it provides an alternative

to classic lithotomy position. However, it is important to gain more experience

in the use of this position and we must consider studying other parameters

that could influence the results and surgical time, like the size of prostate

gland that in some occasions can render the access and the mobility of

the semi-rigid ureteroscope difficult.

REFERENCES

- Pérez-Castro E, Martínez Piñeiro JA: La ureterorrenoscopia transuretral: un actual proceder urológico. Arch Esp Urol. 1980; 33: 445-60.

- Arrabal Martín M, Ocete Martín C, Jiménez Pacheco A, Miján Ortiz JL, Pareja Vilches M, Zuluaga Gómez A: Metodología y límites de la ureteroscopia ambulatoria Arch Esp Urol. 2006; 59: 261-72.

- Angus DG, Webb DR: Influence of hip flexion on the course of the ureter. Ureteroscopic implications. Eur Urol. 1988; 14: 287-90.

- Bercowsky E, Shalhav AL, Elbahnasy AM, Owens E, Clayman RV: The effect of patient position on intrarenal anatomy. J Endourol. 1999; 13: 257-60.

- Herrell SD, Buchanan MG: Flank position ureterorenoscopy: new positional approach to aid in retrograde caliceal stone treatment. J Endourol. 2002; 16: 15-8.

Dr.

Miguel A. Arrabal-Polo

Section of Urology

San Cecilio University Hospital

Granada, Spain

E-mail: arrabalp@ono.com

EDITORIAL COMMENT

Surgeons have historically been particular about patients’ position

during surgery. This is important for access, minimizing pressure points

and prevention of deep vein thrombosis during extended operation time.

Early experience with the rigid ureteroscopy has identified two regions

of the ureter that can be difficult to negotiate, the first at the vesico-ureteric

junction and the second anterior to the iliac bifurcation. During initial

days of ureteroscopy use of large size (13F or plus) ureteroscopes mandated

that all possible efforts should be made to ease passage of the scope

through narrow parts of the ureter. However, there is dearth of scientific

literature on the efficacy of such maneuvers. Korkes and colleagues (1)

have looked into the impact of the outcome on one position (dorsal lithotomy

with leg extended) over traditional dorsal lithotomy. Although they did

not observe any significant advantage of one procedure over the other,

they have noted some advantage in operative time using extended leg position.

More than two decades ago, Angus and Webb (2) noted that the lower ureter

possesses two curves, an upper curve at the iliac bifurcation that straightens

with increasing degrees of lithotomy and a lower vesical curve in the

pelvis, which is unaltered by patient position. Dagnone et al. (3) applied

lower-abdominal pressure to see if it facilitates semi rigid-ureteroscopy

to access to the upper ureter for safe laser lithotripsy using a 7.5F

scope. They observed that lower-abdominal pressure could be helpful to

negotiate passage of the endoscope over the iliac vessels or to place

the laser fiber on stones.

In conclusion, this is a small basic study

looking at an innocuous modification that may have beneficial impact on

the ease of accessing two difficult points in the distal and middle ureter.

In a larger cohort of patients preferably at a multi institutional setting,

future investigators may be able to note a significant difference.

REFERENCES

- Korkes F, Neto ACL, Mattos MH, Pompeo AC, Wroclawski ER: Patient position and semi-rigid ureteroscopy outcomes. Int Braz J Urol. 2009 [In Press]

- Angus DG, Webb DR: Influence of hip flexion on the course of the ureter. Ureteroscopic implications. Eur Urol. 1988; 14: 287-90.

- Dagnone AJ, Blew BD, Pace KT, Honey RJ: Semirigid ureteroscopy of the proximal ureter can be aided by external lower-abdominal pressure. J Endourol. 2005; 19: 342-7.

Dr.

M. Hammad Ather

Associate Professor

Director Urology Residency Program

Aga Khan University

Karachi, Pakistan

E-mail: hammad.ather@aku.edu

EDITORIAL COMMENT

Ureterorenoscopy

(URS), extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (SWL) and percutaneous nephrolithotomy

(PCNL) are the main modalities for modern stone treatment. While all of

these procedures have shown to be as effective minimally invasive treatment

for various stone situations, there are always demands to further excel

their performance. One of the most common ways to improve this situation

is by the help of technological advancement. The development of digital

optics, scope design and auxiliary instruments has greatly improved the

performance of URS and PCNL, in particular flexible instruments (1). Similarly,

there have also been improvements in technology of SWL that can bring

the performance back to the standard set by HM3 (2). However, all these

new developments will inevitably increase the capital cost of medical

treatment, which will be particular important in the current economic

turmoil. As a result, the real impact of these technical advancements

may not be as great as could be expected, especially for the developing

countries.

However, there is also another approach to improve the performance by

modifying the working condition or treatment protocols of the existing

equipment. As well demonstrated by this article, the simple modification

of the leg position will help to improve the performance of semi-rigid

URS (3). This simple and easy approach required no extra-cost for equipment,

but can shorten the operating time, in particular for male patients by

30%. There are also other approaches that have been reported to improve

the performance of URS, such as instillation of lidocaine jelly proximal

to the stone to minimize stone flush back and improve stone free rate

(4). Similarly, modifications of treatment protocols for SWL, such as

modification of shockwave delivery rate (5) and application of gel on

the treatment head (6), has also shown to be effective in the improvement

of treatment outcomes. These kinds of non-costly procedures for improvement

of treatment performance will definitely benefit more patients worldwide

than the simple pursuit of high technological equipment.

One of the pitfalls of this study, as already

discussed by the authors, is the “non-blinded” nature of the

study. As the surgeon performed the operation will know the positioning

of the legs, therefore any subjective preference or bias to one of the

positions may lead to bias in part of the results, such as the operating

time. However, this kind of bias will be intrinsic to most of the surgical

studies and is difficult, if not impossible, to completely eliminate.

Therefore, one should be aware of this bias during the interpretation

of results. Nevertheless, the authors have convincingly demonstrated the

superiority of the dorsal lithotomy position with same side leg slightly

extended (DLEL) over dorsal lithotomy position (DL) during URS. This approach

should be encouraged in our daily practice.

REFERENCES

- Canes D, Desai MM: New technology in the treatment of nephrolithiasis. Curr Opin Urol. 2008; 18: 235-40.

- Nomikos MS, Sowter SJ, Tolley DA: Outcomes using a fourth-generation lithotripter: a new benchmark for comparison? BJU Int. 2007; 100: 1356-60.

- Korkes F, Neto ACL, Mattos MH, Pompeo AC, Wroclawski ER: Patient position and semi-rigid ureteroscopy outcomes. Int Braz J Urol. 2009 [In Press]

- Zehri AA, Ather MH, Siddiqui KM, Sulaiman MN: A randomized clinical trial of lidocaine jelly for prevention of inadvertent retrograde stone migration during pneumatic lithotripsy of ureteral stone. J Urol. 2008; 180: 966-8.

- Semins MJ, Trock BJ, Matlaga BR: The effect of shock wave rate on the outcome of shock wave lithotripsy: a meta-analysis. J Urol. 2008; 179: 194-7; discussion 197.

- Neucks JS, Pishchalnikov YA, Zancanaro AJ, VonDerHaar JN, Williams JC Jr, McAteer JA: Improved acoustic coupling for shock wave lithotripsy. Urol Res. 2008; 36: 61-6.

Dr.

Anthony NG Chi-fai

Associate Professor

Division of Urology

Department of Surgery

The Chinese University of Hong Kong

E-mail: ngcf@surgery.cuhk.edu.hk