EFFECTS

OF CURCUMIN IN AN ORTHOTOPIC MURINE BLADDER TUMOR MODEL

( Download pdf )

KATIA R. M. LEITE, DAHER C. CHADE, ADRIANA SANUDO, BRUNO Y. P. SAKIYAMA, GUSTAVO BATOCCHIO, MIGUEL SROUGI

Laboratory of Medical Investigation (KRML, DCC, AS, BYPS, GB, MS), Department of Urology (LIM55), University of Sao Paulo Medical School, Sao Paulo, Brazil, and Genoa Biotechnology (KRML), Sao Paulo, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Cigarette smoking (CS) is the main risk factor for bladder cancer development. There are more than 100 carcinogens present in cigarette smoke. Among the potential mediators of CS-induced alterations is nuclear factor-kappa (NF-κB), which is responsible for the transcription of genes related to cell transformation, tumor promotion, angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis. Curcumin is a polyphenol compound derived from Curcuma longa that suppress cellular transformation, proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis by down regulating NF-κB and its regulated genes. The aim of our study was to assess the effects of curcumin in bladder urothelial carcinoma. We studied the effects of curcumin in vitro and in vivo using the orthotropic syngeneic bladder tumor animal model MB49. Curcumin promotes apoptosis of bladder tumor cells in vitro. In vivo tumors of animals treated with curcumin were significantly smaller as compared to controls. Using immunohistochemistry, we demonstrated a decrease in the expression of Cox-2 by 8% and Cyclin D1 by 13% in the animals treated with curcumin; both genes regulated by NF-κB and related to cell proliferation. In this study, we showed that curcumin acts in bladder urothelial cancer, possibly dowregulating NF-κB-related genes, and could be an option in the treatment of urothelial neoplasms. The results of our study suggest that further research is warranted to confirm our findings.

Key

words: bladder neoplasms; Cox-2; curcumin; Cyclin D1; NF-κB;

drug therapy

Int Braz J Urol. 2009; 35: 599-607

INTRODUCTION

Bladder

cancer is the sixth most prevalent malignancy in the United States. Progression

and recurrence are recorded in up to 30% and 70% of cases, respectively,

depending on stage, grade, and multifocality (1).

The use of tobacco is one of the main causes of bladder cancer due to

the presence of thousands of different compounds present in cigarette

smoke (CS), of which 100 are known carcinogens, co-carcinogens, mutagens

and/or tumor promoters (2). Among the potential mediators of CS-induced

alterations is nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), whose activation

has been implicated in chemical carcinogenesis and tumorigenesis (3).

NF-κB consists of a group of five proteins that are responsible

for the transcription of genes related to cell transformation, tumor promotion,

angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis (4).

Current treatment for superficial urothelial carcinoma includes endoscopic

tumor resection, followed by intravesical instillation of bacillus Calmette-Guerin

(BCG). However, side effects of BCG therapy are common, and approximately

one-third of patients fail to respond (5). Mitomycin, thiotepa, and epirubicin

have been used as agents to prevent recurrence, but they have no impact

on long-term survival or disease progression. The toxicity and inefficacy

of the intravesical agents prompted us to explore new treatments for superficial

urothelial carcinoma of the bladder.

Curcumin [1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxy phenyl)-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione]

is a phenolic compound, the main ingredient of Curcuma longa. It is extracted

as a yellow pigment from the rhizome, which has been used extensively

in curries and mustards with well-known anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant

and anti-carcinogenic activities (6,7). Curcumin has been shown to suppress

NF-κB activation induced by inflammatory stimuli, to inhibit the

activation of IκBα activity needed for NF-κB activation

and to downregulate the expression of various NF-κB genes, such

as Bcl-2, COX-2, MMP9, TNF, cyclin D1, and adhesion molecules (8).

Syngeneic animal models are often used to study new therapeutic agents.

In our experiment, we used the syngeneic orthotopic murine bladder cancer

model derived from the MB49 tumor cell line. It is characterized by the

transplantation of carcinogen-induced bladder cancer into syngeneic immunocompetent

mice (9,10). This murine bladder tumor model has been considered appropriate

for this purpose, considering its ability to mimic intravesical conditions.

Moreover, it allowed us to test the local tumor response to drugs in an

immunocompetent host (11). Our aim was to investigate the effects of curcumin

in this animal model of bladder cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

AlamarBlue was purchased from Biosource (Camarillo - CA, USA, cat.# DAL1025), curcumin (cat.# C1386) was acquired from Sigma (St. Louis - MO, USA) and TPP 96-well tissue culture microplates were from TPP (Trasadingen, Switzerland). DMEM media supplemented with 100 U/mL of penicillin and 100 µg/mL of streptomycin, serum fetal bovine, and Trypsin-EDTA solution were purchased from CultiLab (Campinas - SP, Brazil).

Curcumin Cytotoxicity Assay

In the cytotoxicity assay, 5x104 confluent monolayer adherent MB49 cells grown in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% of serum fetal bovine, 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 µg/mL of streptomycin were seeded in a 96-well tissue culture microplate and maintained for 24 hours at 37oC in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Thus, cells were exposed to different concentrations of curcumin (from 6 uM up to 400 uM) diluted in a fresh supplemented media for 20 hours in triplicate. After two washings with PBS1x, cells were incubated in fresh media containing 10% of AlamarBlue (resazurin) for three hours, and the reduction level of resazurin was quantified using the microplate reader UVM340 (ASYS Hitech, Eugendorf - Austria) which measured the difference between the density optics of wavelengths 570 and 600 κm. As a 0% viability control (ODmin), triton X 100 (1% of final concentration) was added to the cells one hour before the changing of media. The complete media without curcumin was used as 100% viability control (ODmax). This experiment was repeated twice.

Animal Model

The technique of the establishment of animal tumor model was already described by Chade et al. (10), briefly: Eight to ten-week-old female C57BL/6 mice, weighing 15-20g, were provided by the University of Sao Paulo and maintained at our animal care facility for one week prior to use. The mice were housed in groups of five per cage in a limited-access area at a controlled room temperature, with food and water ad libitum. The experiments were approved by the institution’s ethical board council.

Tumor Cell Line

The murine transitional cell carcinoma cell line MB49 (MB49) was a gift from Dr. Yi Lou (University of Iowa, USA). The cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Cultilab, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil), 1% L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. Tumor cells were harvested by trypsinization and suspended in DMEM without L-glutamine, FBS, and antibiotics.

Orthotopic Tumor Implantation

Six- to eight-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were administered general anesthesia with i.p. injection of a mixture of xylazine-ketamine (0.1 mL/10g/mouse). Then, a 24-gauge Teflon i.v. catheter (Nipro Medical Ltda, Sorocaba, SP, Brazil) was inserted through the urethra into the bladder using an inert lubricant (sterile contact gel). In order to prepare the bladder for tumor implantation, a chemical lesion on the bladder wall was made by intravesical instillation of 0.3 M AgNO3 (8 µL). This promoted an adequate and controlled diffuse bladder wall cauterization. After 10 seconds, the content was washed out by transurethral infusion of PBS. Then, a suspension of 1 x 105 viable tumor cells was instilled into the bladder.

Curcumin Treatment

Twenty-four hours following tumor implantation, intravesical curcumin (Sigma) therapy was initiated. Mice were randomly assigned to either a control group receiving diluents (n = 12) or a treatment group (n = 18). One of the animals of the treated group died during the anesthetic procedure, and 17 remained to be studied. The curcumin doses used were 100 µM per mouse, twice a week, for per urethral treatment under light anesthesia. For comparison, four animals received the curcumin with no previous induction of tumor to verify possible toxic effects of the substance in the bladder mucosa.

Assessment of Tumor

The mice were evaluated on a daily basis for viability and gross hematuria, and after 30 days following tumor implantation they were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation. The bladder was resected and weighed without urine or blood.

Histopathology Analysis

The specimens were fixed in buffered formalin 10%, and sectioned for histological examination. Tumors were measured under the microscope using a scale, and the degree of necrosis and level of tumor invasion into the bladder wall were recorded for comparison. All slides were examined by the same pathologist.

Immunohistochemistry

Three-micrometer sections from the paraffin block were placed on adhesive-coated slides. In a heated antigen retrieval process, the slides were placed in a citrate buffer (1 mM, pH 6.0) and heated for 30 min in the steamer. The slides were incubated overnight at 4ºC with monoclonal antibodies to Bcl2, 1:200 dilution (Dako Cytomation, CA, USA), Cyclin D1, 1:50 dilution (Dako Cytomation, CA, USA), and Cox-2, 1:200 dilution (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) in bovine serum albumin (BSA). The LSAB system was used for immunostaining (LSAB; Dako Cytomation, CA, USA). Color was developed by reaction with 3.3’ diaminobenzidine substrate-chromogen solution, followed by counterstaining with Harris hematoxylin, dehydrated, coverslipped, and reviewed under light microscope. Cyclin D1 expression is exclusively nuclear, and both Bcl2 and Cox-2 have a cytoplasmic pattern of staining.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical

analyses were performed by using SPSS 16.0 for Windows. The numeric variables

are presented as mean and standard deviation, or median and range. We

used the Student’s-t- test or the Mann-Whitney test for the evaluation

of numerical variables and Fisher’s chi-square test for categorical

variables. Results were considered significant when the p value was lower

than 5% (p < 0.05).

RESULTS

In Vitro Studies

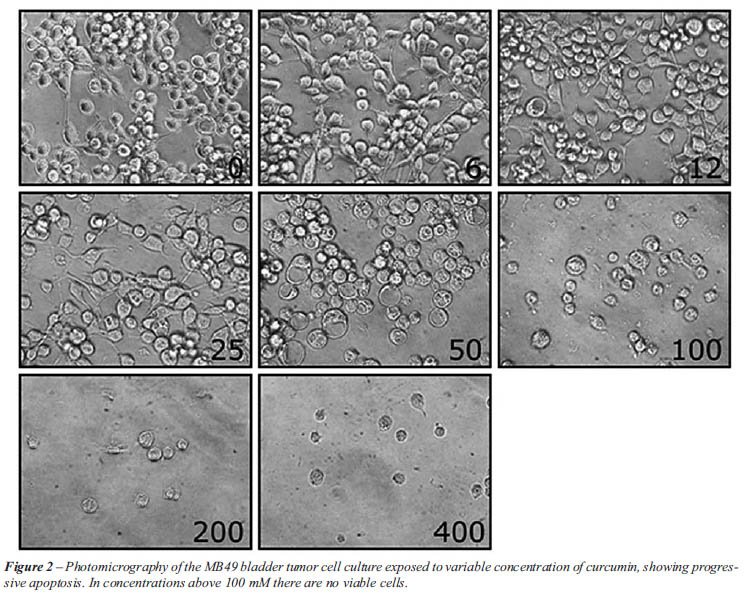

After 24 hours of incubation, 55% of tumors cells exposed to 50 µM of curcumin died by apoptosis, and at concentrations above 100 µM were able to induce apoptosis in 100% of the tumor cells (Figure-1). Figure-2 shows that cells exposed to 50 µM of curcumin lost their elongated shape and had vacuoles in the cytoplasm.

In Vivo Studies

There was

no statistical difference between the two groups with regards to changes

in body weight. The mean weight of the animals at the beginning of the

experiment was 20.3g (SD = 0.8) for controls and 20.7g (SD = 0.9) for

treated animals. At the end of the experiment, the weight for controls

and treated animals were 20.3g (SD = 0.9) and 20.4g (SD = 1.1), respectively

(p = 0.293). Hematuria was present at the 14th day in five (41.7%) mice

in the control group and in only two (11.8%) of the group treated with

intravesical curcumin. This difference was also not statistically significant

(p = 0.092).

The median bladder weight of control animals was 0.059g (range 0.02 -

0.18) and 0.069g (range 0.03 - 0.25) for treated mice. There was no statistical

difference for this parameter between the groups (p = 0.556).

There was a statistical difference between the two groups of animals with

regards to tumor size. The mean tumor size (larger microscopic diameter)

was 0.40 cm (SD ± 0.14) for the treated group and 0.52 cm (SD ±

0.14) for controls (p = 0.048).

There were no differences in the degree of necrosis or level of invasion

of the neoplasia for the two groups. Necrosis was very frequent and accounted

for 30% to 60% of tumor extension for both groups (p = 0.548) (Figure-3).

There was no superficial, non-invasive bladder cancer. Tumors most frequently

invaded the muscular wall in 70% of controls and 80% of treated mice.

There was no statistical difference between the groups in tumor invasion

(p = 0.653).

Four animals with no tumors were treated with curcumin to show the effect

of the substance in the health bladder mucosa. Histologically, the appearance

of urothelium was unremarkable, and no alteration was observed in the

lamina propria or in the muscle wall.

Immunohistochemical

Expression of Cyclin D1, Bcl2 and Cox-2

Cyclin expression was strong, diffuse and exclusively nuclear (Figure-4A). It was positive in 81.8% of the controls and in 68.8% of treated animals (p = 0.662). The staining pattern of Cox-2 was cytoplasmic, diffuse, and stronger in the deep invasive edge (Figure-4B). It was positive in 45.5% of the controls and in 37.5% of the animals treated with curcumin (p = 0.710). Bcl2 was mildly expressed in only one case of the group of treated animals (p > 0.999). Although the expression of Cyclin D1 and Cox-2 was lower in curcumin-treated animals than in controls, statistical tests did not find significant differences between the groups.

COMMENTS

Curcumin

is a polyphenol compound derived from Curcuma longa Linn that has anti-inflammatory

effects, suppressing cellular transformation, proliferation, invasion,

angiogenesis, and metastasis through an as-yet unrecognized mechanism.

In this preliminary study, we have shown that curcumin promotes apoptosis

in MB49 mouse bladder tumor cells in vitro and causes a decrease in tumor

size in a syngeneic orthotopic murine bladder cancer model derived from

the MB49 tumor cell line. We demonstrated that tumors were significantly

smaller in the treated group, which suggests that curcumin could be an

option for treatment of bladder cancer.

Curcumin is not well-absorbed orally, which is a disadvantage in its use

as a treatment for cancer. However, direct contact with bladder tumor

cells has already been shown to be able to inhibit proliferation and induce

cell cycle arrest and DNA fragmentation. Also, increases in rates of apoptosis

have been registered when curcumin has been used as an adjuvant with gemcitabine

and paclitaxel (12).

The standard of care in the treatment of non-invasive bladder cancer (pTa)

or tumors compromising the lamina propria (pT1) is transurethral resection

(TUR); unfortunately, 45% of patients will have tumor recurrence within

12 months following TUR alone. Tumor recurrence is associated with missed

tumors, incomplete resection, implantation of tumor cells at the time

of resection, and/or a de novo tumor growth related to the cancerization

field. Progression to invasive muscle or metastatic bladder cancer has

also been reported in 3% to 15% of cases. The adjuvant local instillation

of mitomycin C and BCG following TUR reduces the probability of disease

recurrence, but has no impact on tumor progression or mortality (13).

To date, no single chemotherapy agent can be considered successful in

the treatment of bladder cancer; consequently, there is a room for the

search of new agents that could be used to treat this neoplasia.

Cigarette smoking is the most important risk factor related to bladder

urothelial carcinomas, and it has already been shown that carcinogenic

substances present in tobacco activate NF-κB; these substances

are related to the proliferative, proinflammatory and proangiogenic factors

associated with aggressive tumor growth.

Aggarwal et al. (8) first postulated that curcumin mediates its activity

by modulating NF-κB activation. Curcumin inhibits TNF-induced NF-κB-dependent

reporter gene expression in a dose-dependent manner, acting on the regulation

of Cox-2 and Cyclin D1, which related to tumor cell proliferation, and

Bcl2, a protein with anti-apoptotic activity. In our animal model, there

was a reduction in immune expression of Cyclin D1 and Cox-2 in more than

13% and 8% of cases, respectively, in bladder tumor cells of the group

of mice treated with curcumin. Although there was no statistical difference,

the reduction could have some clinical importance that could not be proven

due to the small number of animals in the study, or the aggressiveness

of the tumor of this animal model.

This is the first study with curcumin using an orthotopic, syngeneic bladder

cancer model, and the results confirm in vitro experiments published by

other authors. Park et al. showed a reduction in Cox-2 expression after

exposure of T24 bladder tumor cells to curcumin (14). More recently, Chadalapaka

et al. reported inhibition of 253JB-V and KU7 bladder cancer cell growth

using 10 to 25 mM/L of curcumin, showing a decrease in the expression

of NF-κB-dependent genes, Cyclin D1, survivin and Bcl2 (15).

One of the main concerns for the indication of a new therapy is the potentially

toxic effect it may cause. To test for any potential toxic effects of

curcumin in normal urothelium, we applied curcumin in four control mice.

The animals did not present any symptoms and no histological abnormalities

were seen in the mucosa of their bladder, showing that the intravesical

use of curcumin was safe.

Although this is an experimental study using an in vivo orthotopic bladder

cancer model, it is the first to show that curcumin can play a role in

the treatment of urothelial carcinomas regulating the NF-κB-regulated

genes. The results of our study suggest that further research is warranted

to confirm our findings in a larger patient population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Mr. Isaque Santana performed the immunohistochemical slides. Dr. Ricardo Borra and Dr. Priscila Borra helped in the “in vivo” studies.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Malkowicz SB: Management of Superficial Bladder Cancer. In: Walsh PC, Retik AB Vaughan Jr ED, et al. (eds.), Campbell’s Urology. WB Saunders, Philadelphia. 2002; 8th ed., pp. 2785-802.

- Hoffmann D, Hoffmann I, El-Bayoumy K: The less harmful cigarette: a controversial issue. a tribute to Ernst L. Wynder. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001; 14: 767-90.

- Kim DW, Sovak MA, Zanieski G, Nonet G, Romieu-Mourez R, Lau AW, et al.: Activation of NF-kappaB/Rel occurs early during neoplastic transformation of mammary cells. Carcinogenesis. 2000; 21: 871-9.

- Garg A, Aggarwal BB: Nuclear transcription factor-kappaB as a target for cancer drug development. Leukemia. 2002; 16: 1053-68.

- Herr HW, Wartinger DD, Fair WR, Oettgen HF: Bacillus Calmette-Guerin therapy for superficial bladder cancer: a 10-year followup. J Urol. 1992; 147: 1020-3.

- Aggarwal BB, Harikumar KB: Potential therapeutic effects of curcumin, the anti-inflammatory agent, against neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, pulmonary, metabolic, autoimmune and neoplastic diseases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009; 41: 40-59.

- Piantino CB, Salvadori FA, Ayres PP, Kato RB, Srougi V, Leite KR, Srougi M. An evaluation of the anti-neoplastic activity of curcumin in prostate cancer cell lines. Int Braz J Urol. 2009; 35: 354-60.

- Aggarwal S, Ichikawa H, Takada Y, Sandur SK, Shishodia S, Aggarwal BB: Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) down-regulates expression of cell proliferation and antiapoptotic and metastatic gene products through suppression of IkappaBalpha kinase and Akt activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2006; 69: 195-206.

- Günther JH, Jurczok A, Wulf T, Brandau S, Deinert I, Jocham D, et al.: Optimizing syngeneic orthotopic murine bladder cancer (MB49). Cancer Res. 1999; 59: 2834-7.

- Chade DC, Andrade PM, Borra RC, Leite KR, Andrade E, Villanova FE, et al.: Histopathological characterization of a syngeneic orthotopic murine bladder cancer model. Int Braz J Urol. 2008; 34: 220-6; discussion 226-9.

- Fodor I, Timiryasova T, Denes B, Yoshida J, Ruckle H, Lilly M: Vaccinia virus mediated p53 gene therapy for bladder cancer in an orthotopic murine model. J Urol. 2005; 173: 604-9.

- Kamat AM, Sethi G, Aggarwal BB: Curcumin potentiates the apoptotic effects of chemotherapeutic agents and cytokines through down-regulation of nuclear factor-kappaB and nuclear factor-kappaB-regulated gene products in IFN-alpha-sensitive and IFN-alpha-resistant human bladder cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007; 6: 1022-30.

- Hall MC, Chang SS, Dalbagni G, Pruthi RS, Seigne JD, Skinner EC, et al.: Guideline for the management of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (stages Ta, T1, and Tis): 2007 update. J Urol. 2007; 178: 2314-30.

- Park C, Kim GY, Kim GD, Choi BT, Park YM, Choi YH: Induction of G2/M arrest and inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 activity by curcumin in human bladder cancer T24 cells. Oncol Rep. 2006; 15: 1225-31.

- Chadalapaka G, Jutooru I, Chintharlapalli S, Papineni S, Smith R 3rd, Li X, et al.: Curcumin decreases specificity protein expression in bladder cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008; 68: 5345-54.

____________________

Accepted after revision:

July 6, 2009

_______________________

Correspondence address:

Dr. Katia Ramos Moreira Leite

Rua Adma Jafet, 91

Sao Paulo, SP, 01308-050, Brazil

Fax: +55 11 3231-2249

E-mail: katiaramos@uol.com.br

EDITORIAL COMMENT

This is

an interesting proof of concept study looking at the role of intravesical

curcumin in the management of bladder cancer. Cigarette smoking is a well-known

carcinogen of bladder cancer, with a potential mediator being nuclear

factor kappa which, together with downstream targets (Cyclin D1,Cox-2),

may be downregulated by curcumin.

This study has proven the ability to develop an in vivo clinical model

for muscle invasive bladder cancer, and curcumin led to a significant

reduction in size of the cancers however there was no reduction in progression,

and as such its ability to improve survival remains speculative.

As stated by the authors, the numbers of animals used remains small, the

duration of tumor inoculation is short, the mechanism of action or curcumin

remains obscure, and the model, whilst successful in the development of

invasive cancers, may not be applicable to the usual type of bladder cancer

we would treat with intravesical therapy; namely recurrent Ta, CIS or

high grade T1 lesions.

Nonetheless, the authors should be commended for their efforts and the

success of their in vivo bladder cancer model, and curcumin is certainly

worthy of future study given its low toxicity in control animals and apparent

activity in reducing the size of invasive bladder cancer.

Dr.

Mark Frydenberg

Chair, Department of Urology

Monash Medical Center

Melbourne, Australia

Chair, Urologic Oncology Special Advisory Group

Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand

E-mail: frydenberg@optusnet.com.au

EDITORIAL COMMENT

This fascinating

manuscript describes the use of a novel anticancer agent, curcumin, for

treating urothelial tumors of the bladder. Though the work represents

a relatively small preclinical animal study, I find the results compelling

enough for further comment.

There is a paucity of novel anticancer agents currently under investigation

for bladder cancer. That the authors chose to test curcumin, a natural

derivative of the common Indian spice turmeric, is itself interesting.

Turmeric has been attributed medical benefits for millennia, ranging from

the healing gastrointestinal problems to preventing modern cognitive dysfunction

(1). Turmeric is also ingested daily by hundreds of thousands of people

on the Indian Subcontinent (as well as by Indian food aficionados like

myself that are scattered throughout the world). It is conceivable that

turmeric consumption may partially account for the very low rates of bladder

cancer seen in the India compared to other South Asian countries (2).

As all good studies should, this study begs a number of follow-up questions.

Does curcumin administration prolong the survival of mice with bladder

cancer? Will curcumin work when administered later in the tumor advancement

pathway (i.e. 24 hours after cancer cell instillation is probably unrealistically

early to begin therapy)? Will it protect human patients that previously

had bladder cancer, but are currently tumor free, from recurrences? Can

it be made into a form that is orally administrable? Can it be made cheaply

for safe human administration?

REFERENCES

1. Hatcher

H, Planalp R, Cho J, Torti FM, Torti SV: Curcumin: from ancient medicine

to current clinical trials. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008; 65: 1631-52.

2. Parkin DM, Whelan SL, Ferlay J, Teppo L, Thomas DB: (ed.), Cancer Incidence

in Five Continents Vol. VIII. IARC Scientific Publications No. 155. Lyon,

France, International Agency for Research on Cancer 2002.

Dr.

Brant A. Inman

Division of Urology

Duke University Medical Center

Durham, North Carolina, USA

E-mail: brant.inman@duke.edu